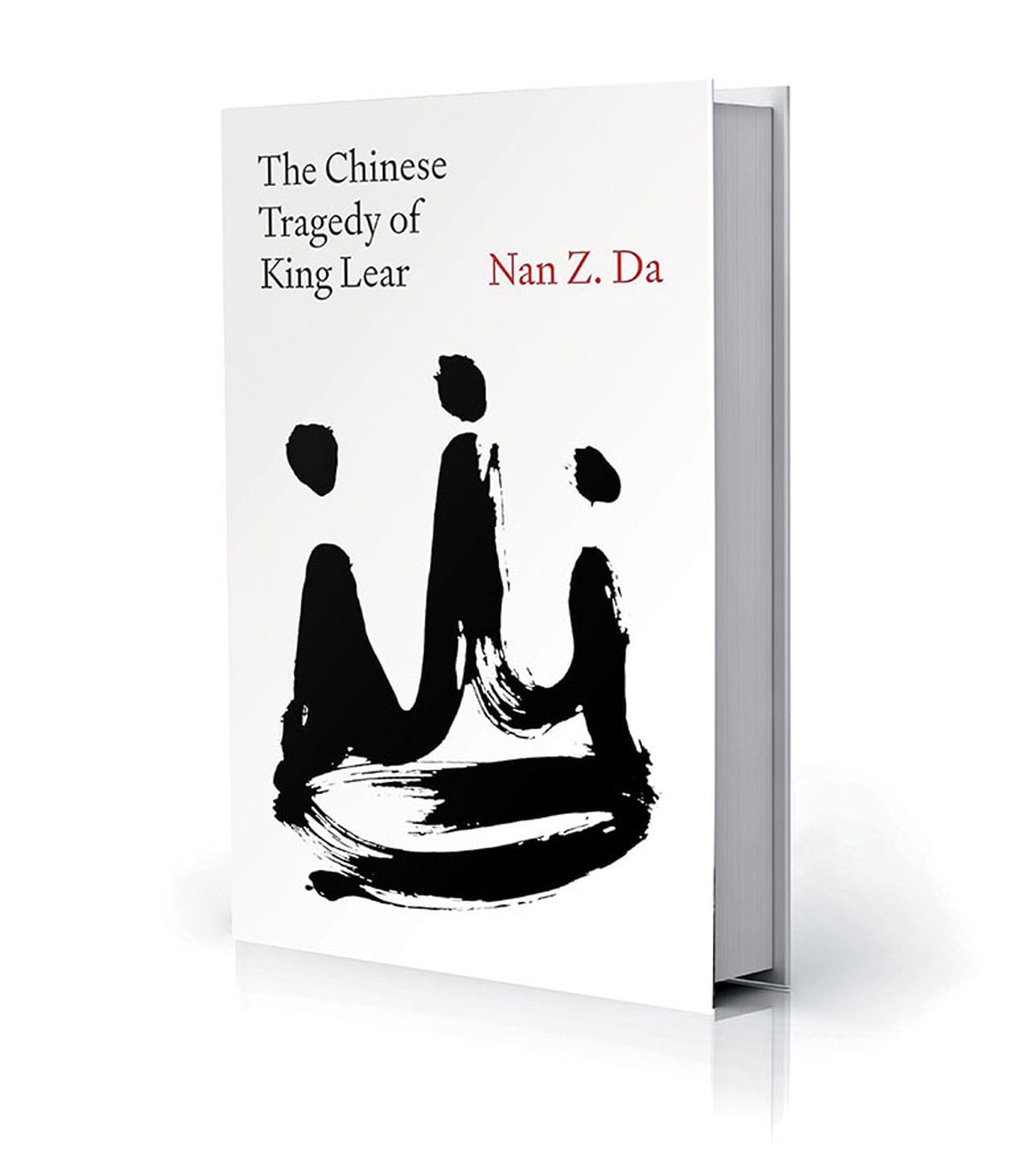

What do Shakespeare’s King Lear and 20th-century Chinese history have in common? Quite a lot, according to Nan Z. Da, an associate professor of English.

In her latest book, The Chinese Tragedy of King Lear, Da uses the lens of literary criticism to dissect the play while relating it to modern Chinese history and her own family’s history, casting herself and her ancestors as witnesses and participants in that history. She presents a new, multilayered perspective on both King Lear and Chinese history.

“What happened in China in the long 20th century to millions, then to more than a billion people, resembled Lear’s imagined and actual worlds: a plague, a regime change, political paranoia, persecutions that were religious and theatrical in nature,” Da writes.

“What happened in China in the long 20th century to millions, then to more than a billion people, resembled Lear’s imagined and actual worlds…”

Nan Z. Da

Questions of filial piety

In the Shakespeare tragedy, Lear plans to divide his kingdom among his three daughters but deprives the one who does not extravagantly flatter him. Instead splits it between his older daughters, Goneril and Regan, and disowns his loyal daughter Cordelia. He is betrayed by the older daughters and spirals into madness. The deceit and betrayal in the play cause war, and eventually lead to many deaths, including those of Lear and his daughters.

For Da, who emigrated from China to the United States as a child in the early 1990s, the heavy themes of the play make it what she calls Shakespeare’s “most Chinese” play. For one, it probes filial piety—questioning what is actually owed from children to their parents and elders. It also connects the brutalization within a family back to the state—“to embed at the heart of history a dysfunctional family,” she says.

“Lear is a story about parents who are gaslighting their children and children who are gaslighting their parents and discrediting them,” she says. “Across the Chinese diaspora, you see this kind of double movement of needing excessive flattery and affirmation, not getting it, or getting it and then being deflated … because Maoism was such an ego-destroying institution.”

Modern China and Lear

Da writes that current Chinese President Xi Jinping is “still stuck in his own Learian tragedy.” His father, a former propaganda minister, was purged and persecuted, including by members of his own family. When Xi and his siblings were sent to a remote part of North China, his mother participated in the denunciation ceremony.

Throughout the book, Da chronicles her own family history, including her grandparents’ almost blind devotion to the party that would so cruelly punish them. In one incident, her grandfather and his fellow members of the transportation bureau are made to crawl in a line for eight hours on a road they’d built years ago for “fidelity to the state’s persona non grata.”

Ultimately, Da hopes readers will appreciate the role of literary criticism in analyzing the concept of evil and wronging of others. Examples of which can be found throughout Lear and Chinese history.

“Things that are particularly evil are hard on the mind, and they’re hard to actually depict. They’re hard to remember, hard to represent, they’re hard to give an account of,” she says. “Literary criticism has a particular handle on evil.”