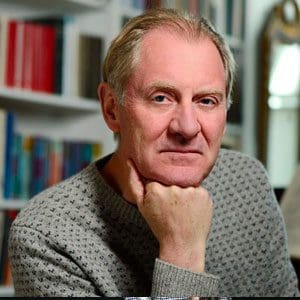

Poet Andrew Motion doesn’t care for poems that are “too tidy for their own good.” Rather, he wants them to “imitate the mystery and unpredictability of life.”

The arbitrary nature of human existence is on full display in his 14th volume of poetry, Randomly Moving Particles, published last year. Motion, who is Homewood Professor of the Arts in The Writing Seminars, has divided this latest collection into three parts. The first section comprises myriad fragmented parts into one poem that bears the title of the collection.

“I wanted to write a poem that moved in a jagged line,” Motion explains. “Poems can be like disrupters.”

The poet ruminates on the seemingly inconsequential and makes it sing:

“As surprising really but in its way as simple

as a god moving among his earthly inferiors,

a flock of sparrows bursts from a dust-bowl

and sinks into bare branches of a sycamore.

Dark matter of randomly moving particles.”

Then he turns to address the vast and unknown:

“I climb onto my roof to count the stars

and see beyond them gas nebulae

flaring like ideas that start before words

and instantly die.”

Discussing Big Questions with Poetry

Motion says he wants to address big questions in his work, such as, Where does a person belong?

“Where do humans fit in between the smallness of insects and the infinity of space?” he says. “The way we define our humanity has a great deal to do with how we relate to other humans and the phenomenal world.”

The first section of the book also includes parts about Motion’s adopted home, Baltimore. Born in London and raised in the countryside of East Anglia, Motion came to Johns Hopkins in 2017 after holding various positions in the United Kingdom, including Poet Laureate from 1999 until 2009. Usually, the poet laureate position is a lifetime royal appointment but when he was selected for the title, Motion agreed to accept but only for 10 years. During that time, he founded The Poetry Archive, a free, online audio library of poets reading their work. It holds more than 20,000 poems and ensures that the oral record of modern poets is not lost.

How to Explore the Poetry Archive

The site is designed so that someone using it for the first time will look for a poet they know, and be led on a tour through wonderful poets they never knew existed. Some of Motion’s favorites include:

- Alfred Tennyson’s “Charge of the Light Brigade.” It’s one of the earliest known recordings of a poet reading their work.

- Charles Causley’s “Eden Rock.” The author knew he was reading the poem for the last time.

- Grace Nichols “Hurricane Hits England.” Nichols has enriched the voices of Black British writers for 50 years.

Motion’s Baltimore Poetry

Motion says that he still feels somewhat of a stranger in Baltimore and continues to be shocked by the level of violence, inequity, and racism in the city.

“I’m starting to feel more familiar here,” he says, “but I never want to stop being shocked by these things so I can keep protesting them through my work.”

Motion writes about the contrasting ugliness and beauty of Baltimore:

“Downtown past the haunted high rises and blind eyes

of Gotham-Golgotha scattering underground steam-

bursts,

last gasps exhaling whatever trash Ratking snacks on

beneath,

until finally out and through into widening brighter

light

I go with gorgeous silvery Chesapeake sky overreaching.”

The second section of the collection comprises three poems which, while incorporating some themes of the first part, also address evolution and the ominous dangers of climate change.

“We are a resilient and ingenious species, but we refuse to learn from the lessons of history. I feel like I would not be fulfilling my responsibilities to the world if I didn’t write about some of these issues,” says Motion.

The final section is a haunting poem called “How Do the Dead Walk,” about Major H, a veteran of the war in Afghanistan who loses his grip on reality and kills his father, wife, and children. Motion says several things motivated him to write the poem, including a project he did for the BBC, where he interviewed the last British troops to return from Afghanistan. He was also influenced by writer Anne Carson’s translation of four plays by Euripides, including one in which the hero destroys his own family.

“Also, for decades, an incident from my childhood has been stuck in my brain, and I drew on that as well,” he says. Motion grew up in the quiet countryside, but one day, a shocking episode of domestic violence happened at a farmhouse down the road. A son murdered his parents, his sister, and her children. “I wanted to explore how one makes sense of such inexplicable violence,” he says.

“He never did catch the moment itself

the turbulent stop

and slop of the world

as it swerved in another direction.

*

Get a grip Major H.

get

a

bloody

grip.”

Motion is teaching two courses this semester: a graduate course on British poetry and an undergraduate course called International Voices, in which he strives to “increase the diversity of [his students’] reading menu” by including writers who are African American, Caribbean, Indian, South African, Native American, and Australian.

When asked about advice for budding poets, Motion says, “Don’t separate reality from writing. Don’t live in an ivory tower. Live in life. Realize that every word matters. Think carefully about even the least-seeming word. Remember to look at the ordinary things. Have faith that it matters.”

Read Along with Motion

Add this selection of books from Motion’s International Voices syllabus to your reading list to learn more.