Most women in Revolutionary-era America had little education and few opportunities to write about the young country that men were forging around them.

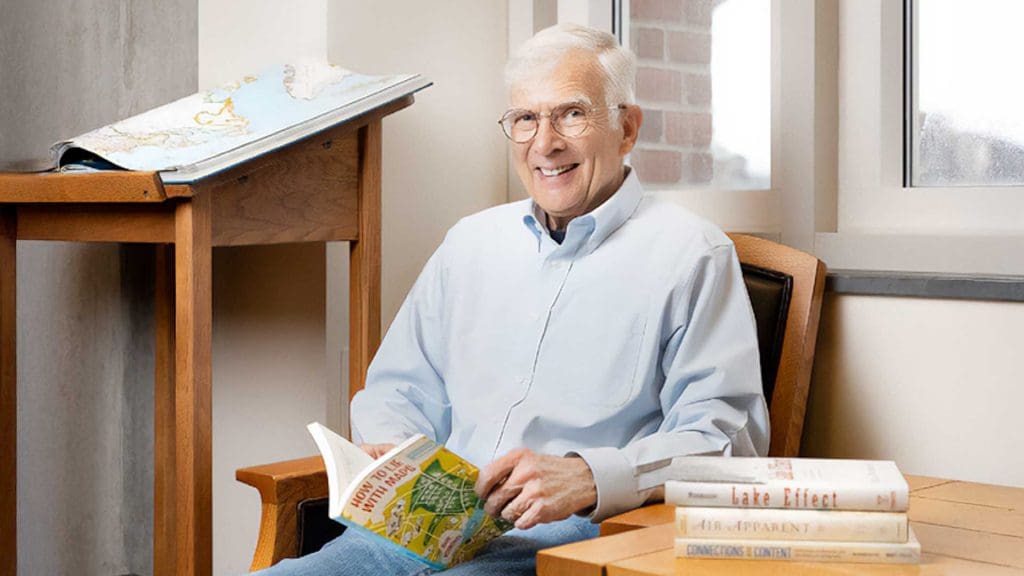

Hilary Gallito ’25 is studying the words of three remarkable women— two wealthy and white, one formerly enslaved—who managed to make their voices heard.

Catharine Macaulay, Phillis Wheatley, and Mercy Otis Warren all lived in and wrote about Revolutionary America, making connections to ancient Greek and Roman ideas as they publicly examined their own tumultuous times.

Women’s work

“I want to show that women were concerned with the classics in colonial America,” says Gallito, who is pursuing simultaneous undergraduate and master’s degrees in history, as well as a double major in classics. “It was important to how they thought about what this new idea of America could look like.”

Mercy Otis Warren, who lived from 1728 to 1814, used ancient history to skewer the politics of the time in her satirical plays and poems.

The renowned poet Phillis Wheatley was emancipated after the 1773 publication of her first book, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, which referenced classical life and culture while exploring questions of American identity and slavery.

English historian Catharine Macaulay alluded to ancient Greece and Rome as models of government and morality as she advocated for the principles on which the United States was founded.

Where research meets art

Gallito grew up in Cleveland and developed an interest in the classics while studying Ancient Greek in high school. She chose Johns Hopkins because she wanted a research-focused school that was in a city.

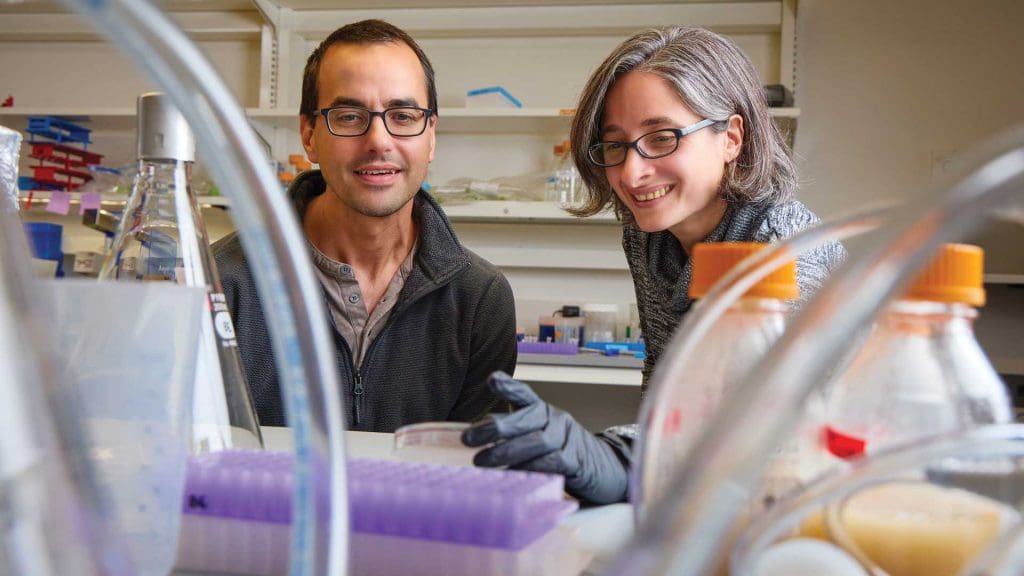

Her involvement with the Antioch Recovery Project, a Hopkins research lab that studies ancient mosaics from the city of Antioch-on-the-Orontes in southern Turkey, cemented for her the satisfactions of using rigorous research to better understand history and art.

In another class, she wrote about the Maryland Gazette, which for several years was run by Anne Catherine Hoof Green, one of the first female editor/ publishers in the Colonies. The paper’s “Poet’s Corner,” with poems in Greek, Latin, or translations of either, underscored for Gallito that women at the time were interested in antiquity as well as in the changing world around them.

Gallito, who won a $6,000 Provost’s Undergraduate Research Award (PURA) to pursue her research, expects to complete a 100- to 150-page work by spring. The funding has given her freedom to visit archives in Boston and elsewhere, where she can examine the handwritten notes of these brilliant and brave women.

“Seeing the way people wrote, seeing what words they scratched out in letters and how they rewrote them, has all made it come much more alive for me,” she says.