Many faculty and students at the Krieger School weave the city of Baltimore itself into their research and scholarship. Some turn to its forests and waterways to plumb ecological principles and search for solutions to environmental challenges, while others look to its residents to tell their own stories or offer solutions to pressing issues, grounded in these citizens’ own lived experience.

At its best, this kind of research—in and of the city—engages with the community as an equal partner, with researchers both learning and teaching, following and leading…and always listening.

We share a few examples of this approach in 10 stories that highlight partnerships based on schools, community building, or the environment.

Getting Kids Hooked on Complex Science

Sparking a passion for science needs to start at a young age. Biology professor Steven Farber and program director Valerie Butler have devised a unique way to do just that. Their secret? Zebrafish. Farber and Butler work side by side with science teachers in Baltimore City schools to develop a series of hands-on science projects that engage young students.

Called BioEYES, the program brings live zebrafish into the classroom. Students learn how to mate the fish, then raise the resulting embryos until they hatch as clear, free-swimming larvae with beating hearts that can be observed under the microscopes provided by the program. Hence the name BioEYES—because the fish are transparent. Students from grade 2 through high school benefit from expert science curriculum in cell biology, genetics, and scientific methods, and get a chance to become scientists. Each day, just like research scientists in the laboratory, students hypothesize and test ideas, ask questions, record findings, and think critically about the impact scientific research has on our community. Students are encouraged to see that science is open to each of them as a career path.

“BioEYES helps kids learn complex topics like microbiology and developmental biology, but in a way that the children absolutely love because they are working hands-on with live fish,” says Butler. “For example, the abstract concept of genetics is illustrated where the pigment traits of the adult fish (stripes or no stripes) can be visualized and observed in their offspring. Genetics is difficult for kids of all ages to grasp, but BioEYES makes learning it interesting and fun.”

Inspiring Young Writers

With the goal of improving racial and economic equity, the nonprofit Writers in Baltimore Schools (WBS) offers creative writing programs to students in Baltimore City Public Schools in small, participatory settings during and after school and over the summer.

The Krieger School’s Writing Seminars department has partnered with WBS since 2016. Current offerings include a community-based learning class each spring for high school writers to take alongside Hopkins undergrads, with topics rotating among poetry, fiction, and nonfiction; a yearlong Teaching Fellows Project for undergrads to study the teaching of writing and then apply their knowledge in Baltimore elementary and middle schools; and a five-week literary editing program for high schoolers that culminates with a publication featuring the work of 4th- through 8th-grade writers.

Kaya Dia ’25, a Writing Seminars major, first connected with WBS in her first year of high school, when a teacher suggested she take a community-based learning class at Hopkins in nonfiction. The experience helped her decide to attend Hopkins, where she’s maintained her connections with WBS.

“Without WBS, I wouldn’t be so certain of myself as a writer,” she says. “It helped me find my footing and realize what I wanted to do in the writing field, and that I wanted that to be my career.”

We share here an excerpt of a short story that Dia wrote in summer 2024.

Excerpt from “Sea Witch”

by Kaya Dia

“Are you sure she’s still there?”

“Would they still tell stories about her if she weren’t?”

Corrine stood on the ferry’s deck, wedged between a pillar patched with off-white paint and M.K. Her friend rummaged through the tote of fruit the ferry captain had mercifully let them take on board. The bag dangled from M.K.’s arm, swaying along with the boat as the waters beneath dragged the vessel over its sea-glass blue. M.K. drew out an apple, handing it to Corrine.

Corrine took it, rolling the fruit between her palms. “They still tell stories about Bette, and she’s long gone,” she said, answering M.K.’s question. The young sculptor had left the island they drifted towards years ago, back when Corrine climbed trees and pretended she was a giant traipsing through the mortal world.

M.K. shook her head. “Bette wasn’t a witch. They don’t move around once they’ve settled somewhere.”

“You’d think it’d be the other way around,” Corrine said. She stared out at the water, resisting the urge to drop her apple into the sea just to see what sound it made.

M.K. shrugged, her shoulder bumping against Corrine’s. “Moving is a vampire’s problem.©

The Right Chemistry

Last spring, chemistry professor David Goldberg’s lab hosted 29 high school juniors and seniors from Baltimore Polytechnic Institute. The students spent the day practicing experiments they had only read about before, explaining the chemistry behind them to their peers through demonstrations, and touring the department’s instruments and facilities.

Goldberg, who has been hosting such workshops off and on for the past 22 years with the help of funding from the National Science Foundation, describes the event as similar to a tutorial session: One graduate student works with two or three high schoolers, talking informally about chemistry.

While the high schoolers get hands-on, practical experience with the science behind the concepts they study, the lab’s graduate students get the chance to practice explaining how the science works to those less experienced.

“For those of us who are looking at possibly working in academia, this provides an opportunity to learn how to break that knowledge down into pieces that they can understand given their current knowledge base,” says graduate student Jacob Wade. “You see in their eyes that they’re learning something.”

Protecting our Democracy

For the past four years, the Elijah E. Cummings Democracy and Freedom Festival has brought together scholars, community members, and policymakers to grapple with challenges facing democracy, model civic engagement across divides, and celebrate democratic resilience and opportunity. Highlights include keynote speakers, moderated debates, and a People’s Dinner, where attendees break bread across lines of difference.

Now hosted by Johns Hopkins’ SNF Agora Institute, the festival was founded by Maya Rockeymoore Cummings in the days following the Capitol insurrection in January 2021, with the first one occurring less than two weeks later. A political scientist, policy analyst, government affairs expert, and nonresident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, Rockeymoore Cummings is a senior fellow at the SNF Agora Institute and the widow of former U.S. Rep. Elijah E. Cummings. We share excerpts of our conversation with her about the festival.

How did the insurrection spark the idea for the festival?

It made me think about how Americans don’t appreciate our form of government because they’re not taught about democracy. We don’t often travel to other countries and directly experience the constraints of undemocratic regimes. We don’t often read about what authoritarian regimes mean for the freedoms that we take for granted. So I decided at that moment that I was going to create a platform to educate and celebrate our form of government.

I deeply appreciate Johns Hopkins University taking the festival on and remaining dedicated to making sure that it happens on an annual basis.

Rep. Cummings had a vision of democracy as something we all build together. How does that actually work?

There’s been the Civil Rights movement, the Women’s Rights movement, the LGBTQ Human Rights movement; all kinds of movements to challenge our democracy to be more responsive and accepting of a broader range of people. That process of challenging and protesting and demanding and creating policy change has made our union more perfect as time goes on. Now our challenge is resisting the retrograde forces who seek to erase those efforts to progress our nation.

What do you want people to understand about democracy?

I want people to understand that our democracy is precious. We take for granted the ability to speak our minds, disagree with those in power, challenge systems, request to change laws. In many countries with authoritarian regimes, you can get killed for speaking your mind.

I also want people to understand that our democracy is fragile. We take for granted that what we have today will always be, and the reality is, that is absolutely not the case. In order to defend and protect our democracy, we have to understand what we have. Then we have to appreciate it. Then we have to protect it. I want people to understand that their vote matters, their voices matter, their participation matters. We have to completely engage in our system of democracy to make sure that forces that would like to undermine and dismantle it do not take hold and succeed.

Watch Now

Highlights from a past Elijah E. Cummings Democracy and Freedom Festival

What do Baltimoreans want?

If you want to know what’s on the minds of Baltimore residents, you have to ask them. They are best equipped to speak frankly about challenges, inequities, and quality of life in this city of more than 550,000 people.

That’s the idea behind the annual Baltimore Area Survey, co-designed by Krieger School researchers in the 21st Century Cities Initiative (21CC) in collaboration with community leaders. The inaugural survey, deployed in 2023, asked questions about food insecurity, policing, transportation, substance use disorder, and other quality-of-life issues. Results were released late last year and are open source.

For Mac McComas, senior program manager in the initiative, the most shocking findings had to do with food insecurity. “Almost 40 percent of Baltimore-area residents reported that in the past year, they worried that their food would run out before they got money to buy more. In addition, 34.4 percent and 35 percent, respectively, reported that their food didn’t last and that they could not afford balanced meals.”

According to sociologist Michael Bader, associate professor and faculty director of 21CC, the survey will provide timely data, measure change over time, and ultimately inform city and state policymakers. He said the survey also documents the disparities that exist between white and Black Baltimoreans, and collecting and analyzing that data “is something we can contribute as a university to the city.”

Preserving Black Archives

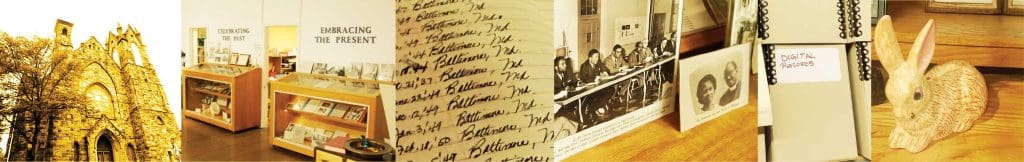

The museum room at Metropolitan United Methodist Church in Baltimore’s Harlem Park neighborhood is an orderly mélange of memories. Church newsletters from 1916 sit across from hand-sewn banners, and even a rabbit made in the church ceramics club.

“Before this, our history was stored upstairs in boxes,” says Eleanor Brown, the chair of Metropolitan’s history committee. “Getting involved in this has made me realize how important it is to share our story. Everyone in this church has a story to tell.”

Metropolitan is one of the historic Black churches that collaborates with the Johns Hopkins’ Inheritance Baltimore (IB) and its Community Archives Program. Since 2021, IB staff and fellows have worked with Metropolitan, St. James Episcopal Church, and Union Baptist Church, as well as the Eubie Blake Cultural Center and the AFRO newspaper, to inventory, manage, and store hundreds of years of artifacts.

This can mean offering advice, digitization or preservation services, providing archival storage boxes or moisture monitors, or creating digital tools like ArcGIS story maps and videos. “We provide support wherever it’s needed for them to preserve their collection, but also to draw attention to the collection,” says Tonika Berkley, Africana archivist with the Sheridan Libraries and co-director of the project. “They contain a treasure trove of not just church history but Black Baltimore history, and Black political history.”

The project also includes public preservation workshops and Sheridan Libraries and Eubie Blake Cultural Center exhibits. “It’s really about them being the cultural stewards of their materials,” says Berkley.

Trans Histories

The Trans Histories Lab is a community-university research project that uses Johns Hopkins resources to empower Baltimore transgender historians. The lab includes undergraduate courses, public workshops, a speaker series, archival acquisitions, and a trans oral history project called Vintage T, where local trans elders share their stories. Vintage T is a collaboration between Baltimore organizers Jamie Grace Alexander, Rahne Alexander, and Monica Yorkman, as well as JHU staff and students, led by Joseph Plaster, director of the Winston Tabb Special Collections Research Center and Curator in Public Humanities in the Sheridan Libraries.

Can you tell us about the oral histories you’ve collected?

JG Alexander: I interviewed my elders—trans people in my community over 50 years [old] who have provided me with guidance. I love the genuine tone of the interviews.

Plaster: The community is a partner in the research, not simply an object of study. Our three collaborators have identified all the research questions, developed the interview guide, and conducted the oral histories. We’ve been able to financially compensate collaborators and narrators and are developing strategies for sharing the results with members of the community.

How do the oral histories intertwine with classes and workshops?

Plaster: I’ve been excited about cross-pollination between courses, lectures, and oral history workshops. We’ve been able to strengthen trans communities at Hopkins and in Baltimore, and at the same time produce new knowledge about gender and sexuality.

Why does this research matter?

Plaster: When there’s been such a violent anti-trans backlash, it feels important to document trans histories—documenting that really rich past in a way that helps strengthen trans communities now and helps us think about what trans futures can look like.

JG Alexander: Hearing from trans elders is a privilege and helps trans youth feel connected to their lineage. These stories are worth listening to.

A View from the Future

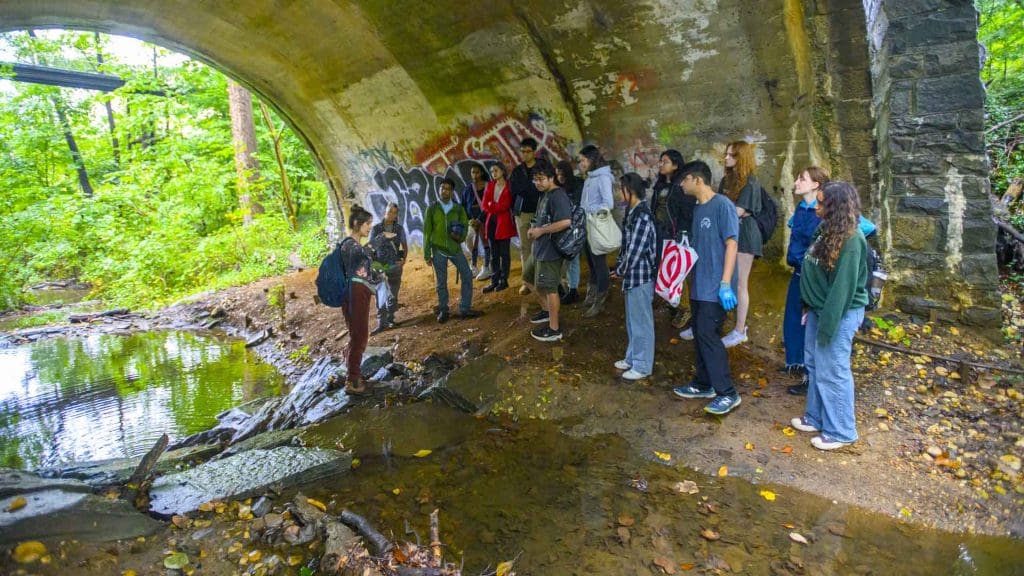

What culture will a future society along Baltimore’s Jones Falls waterway produce, and how will it use what we leave behind?

In their “speculative anthropology” course, co-instructors anthropologist Anand Pandian and local visual artist Jordan Tierney ask students to explore these questions as anthropologists and artists of another time by crafting a story about a culture beyond our fossil-fueled present. Class members this semester are observing nature along the stream near the Homewood campus, collecting materials, and assembling artifacts of a future collective life, which will serve as the foundation of a spring exhibition in a Baltimore museum.

Mapping Trees for Healthier Cities

Planting trees in cities is purported to serve communities and solve environmental ills. But it’s hard for trees to grow in cities, says Meghan Avolio, associate professor of Earth and planetary sciences. They live, grow, and change with their environment. “If I accomplish anything, I just want people to see trees as living organisms in cities,” Avolio says. “They’re cohabitating the city with us.”

Her team of students is collecting data from park trees, street trees, and urban forests to understand what type of trees are in Baltimore, where they are, and how they are faring. To create a robust assessment, they are collaborating with and using existing data from several universities, Baltimore Green Space, the U.S. Forest Service, the City Department of Forestry, TreeBaltimore, and the Baltimore Tree Trust. This research, Avolio says, will help the city make better choices to improve Baltimore’s environment, even in a changing climate.

Soil Searching

On a steamy July morning in an East Baltimore field, a dozen Baltimore young people gently dig up samples of the soil and store them in marked plastic bags ready for heavy metal analysis in the lab. They are guided by Ariana Strasser-King ’27, an environmental studies and public health major. Over the next few weeks, armed with their training from Strasser-King, the students then visited several other sites in East Baltimore, at the request of those communities, to collect samples in spaces that might be slated for future greening, play spaces, or development. The results will help community members understand what is possible and appropriate to grow in these sites and encourage them to practice safer growing methods to reduce their exposure to harmful heavy metals.

The training was offered through the Baltimore Social-Environmental Collaborative (BSEC), a group of researchers and community organizations led by Krieger School scientists. Most of climate change’s heaviest burdens fall on communities already facing the greatest environmental challenges due to underinvestment in urban neighborhoods. BSEC takes a new approach, working in partnership with residents to shape climate-related priorities and guide the work of environmental monitoring and evaluating solutions to extreme heat.

The students were members of YouthWorks—a program of the Baltimore City Mayor’s Office of Employment Development that provides job opportunities to thousands of young people ages 14–21 for five weeks each summer—and were spending their summer placement at the Broadway East Community Association.

“It’s important for them to start to understand where they live,” says Doris Minor-Terrell, president and CEO of the organization.