The most effective HIV prevention programs are tailored carefully to their intended audience, concludes Rachel Burns.

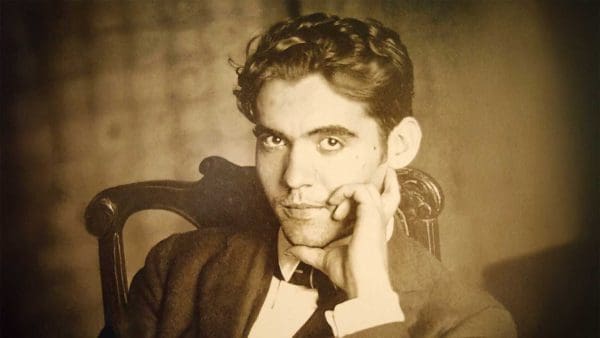

Will Kirk / homewoodphoto.jhu.edu

In 2008, Rachel Burns ’12, then a freshman at Hopkins, read an article in the New York Times Magazine about the HIV/AIDS epidemic in South Africa. The article talked about how foundations were spending millions of dollars on AIDS programs, but there wasn’t any follow-up on which programs were most effective in actually combating the disease and helping those who suffered from it.

“It was a light bulb moment for me,” says Burns, who, at the time, was becoming interested in domestic public health issues through one of her early classes at Johns Hopkins. “There were all these overarching programs, but 25 years after the discovery of the disease, there weren’t people researching the effect of these programs on specific groups.”

So Burns, a public health and anthropology double major, decided to visit four U.S. cities to investigate the effectiveness of various HIV/AIDS awareness and treatment programs on different populations. She began last summer interning with the San Francisco AIDS Foundation and working at a clinic in the predominantly gay Castro District. While there, she interviewed public officials and HIV-positive men and women of a variety of racial and cultural backgrounds and sexual orientations, asking them their opinions on how HIV prevention was handled and how they envisioned it could be changed.

What she found through her empirical observations was a mixed bag on how effectively each population was being served. “I was definitely surprised at how good some treatment was for some groups and how ineffective it was for others,” she says.

For example, in her interviews with some black men, “the interviewees explained that programs targeted at African American males were only aimed at individuals who were much more open with their sexuality than others,” she says. “While they all may have contracted HIV through having sex with other men, that did not necessarily mean that they identified themselves as homosexual. And there was little programming in place for those who did not.”

She did find a success story at the Castro’s Magnet Clinic, which was founded in 2003 with direct input from the community it served. “It’s a clinic run by gay males for gay males in a predominantly gay area. It had a real homey type of feel and looked more like a coffee shop than a clinic, which made it a far more comfortable and approachable place for people to visit.” The clinic provided free testing for HIV and sexually transmitted infections, support groups, town hall meetings, and confidentiality in all their client services.

She spent this past summer in New York City where the needs of the community can differ by neighborhood. “One could think that New York is homogenous and that a clinic model that worked in Harlem would work in [Greenwich] Village, but the communities are incredibly diverse and different, so understanding them first is key.”

This fall, she plans to expand her research to Baltimore and Washington, D.C., which has one of the highest rates of HIV/AIDS infections nationwide. Ultimately, Burns hopes to convince stakeholders that combating AIDS with blanket policies and programs is not as effective as listening to a community and responding to its specific needs.

“I feel like we’re still not listening to the most valuable voices we have—people already suffering from the disease,” she says. “They could make such a difference in determining health policy, and that’s what I want people to take away from my research.”