“When you think about Muslims, you typically think of an Arab or South Asian, but if you were to take a random Muslim out of America, odds are they would be black,” says Rafee Al-Mansur. “African-Americans are the largest Muslim racial group in the U.S., at more than a third of the Muslim-American population, but most people don’t seem to realize it—including other Muslims.”

As part of their Woodrow Wilson fellowships, Al-Mansur, a senior sociology major, and classmate Mohamed Hamouda, a biology major, are producing a documentary film about African-American and immigrant Muslim communities in the Baltimore region.

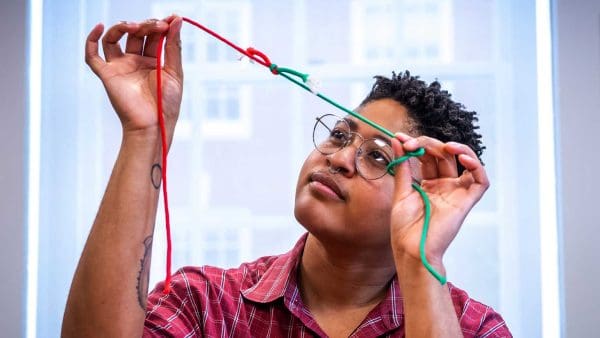

Rafee Al-Mansur (left) and Mohamed Hamouda ’13 work on editing their film about Muslims.

The two communities tend to exist in their own separate worlds, note Al-Mansur and Hamouda, with African-American mosques mainly located in the city and immigrants—and their mosques—in the suburbs. They share the same religious beliefs, but like many separate ethnic groups, tend to keep to themselves. “I don’t think the immigrants really know how to relate to the African-American community,” says Hamouda. “I don’t think it stems from racism, it’s just a cultural thing. Jokes that are funny to them might not be funny to the other group and vice versa.”

Al-Mansur and Hamouda hope their documentary helps change that paradigm. The pair has been filming interviews with both African-American and immigrant Muslims, getting interviewees—from religious leaders to teenagers—to talk about their respective communities. They’ve had subjects share stories about topics ranging from family life to jobs to relationships to the histories of the communities themselves. Their goal is to edit all the interviews into a film that reveals the dynamics of each community. Then the Wilson fellows would like to screen the film for both groups, with the purpose of helping each one understand the other a little better. “Hopefully,” says Al-Mansur, “we’ll also be able to facilitate some connections between the two. Our ultimate goal is to inspire change, not just to do research.”

Both students are second-generation immigrants. Al-Mansur’s parents hail from Bangladesh, and Hamouda’s mother and father come from Algeria and Libya, respectively. Part of the film, the students say, will cover their own journey of discovery as they complete the project. Despite being the child of immigrants, Al-Mansur says he’s found that, in many ways, he can relate to African-American Muslims more than he can to the first-generation immigrants. “I grew up here in America and have experienced a lot of the same things they have,” he says. “I do think that provides hope that maybe second-generation immigrants can bridge the gap between these two communities.”

Both say they were also surprised by the devotion to Islam practiced by African-American Muslim converts—a devotion often stronger than that they witnessed in the immigrant communities, where people are more interested in fitting into American society. “It’s almost like African-Americans are on this journey to becoming Muslims, and immigrant Muslims are on this journey to becoming American,” says Al-Mansur. “But both communities can offer each other a lot. African-Americans are American. They know this country the best and could help immigrant communities with assimilating into America. At the same time, these immigrant Muslims have a lot of knowledge about Islam they can share with black Muslims.”

Both students say it will take time to help unite two disparate groups facing very different challenges. “When we go to these mosques in each community, we can see that the Friday congregational sermons are very different,” says Hamouda. “The needs of an inner-city teenager facing the problems of gangs or drugs can be very different from those of an immigrant teenager. They’re in different situations, and they have to combat different struggles.” But in the end, he says, “what holds us together is that we all testify to the same Islamic declaration of faith: There is no god but God, and Muhammad (peace and blessings be upon him) is His messenger.”