Most of Peter Beilenson’s students have never visited the Baltimore neighborhoods a few miles from the Homewood campus that are depicted in HBO’s The Wire—communities held hostage by poverty, gun violence, and drug addiction.

That’s all the more reason for Beilenson, a physician and the city’s former health commissioner, to challenge his undergraduate students to scrutinize the bleak side of urban life in his provocative course, Baltimore and The Wire.

He uses episodes from the popular television series to illustrate how city institutions have failed to cure Baltimore’s public health problems. Then, the ever-optimistic Beilenson turns each cinematic illustration of despair on its ear, charging students to think like activists to solve Baltimore’s urban crises.

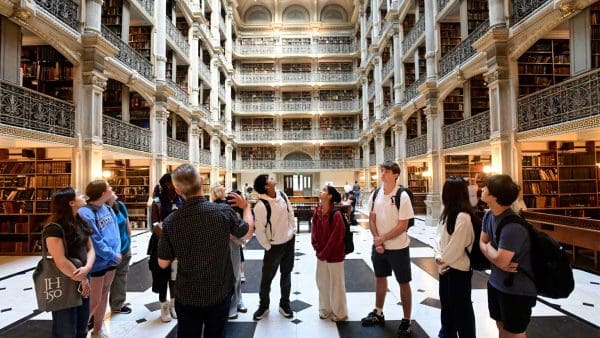

“No matter where you stand on the issues, you need to look at the opportunity to make change happen no matter how you feel about it,” he told more than 100 students packed into a Hodson Hall lecture hall on the first day of class.

“I feel The Wire shining a light on these issues is making people want to do something about it,” he told them.

Beilenson, who holds a master’s in public health from Hopkins’ Bloomberg School, teaches by example. While Baltimore City health commissioner from 1992 to 2005, he introduced the city to a needle exchange program for drug addicts to prevent the spread of AIDS, a controversial birth control program for teenage girls in public schools, and a new law limiting the sale of ammunition. He also posed as a drug addict to infiltrate the poorly functioning system of drug treatment programs, examining problems firsthand before streamlining the system to make access easier for addicts.

Throughout the semester, students read about successes in public policy in Beilenson’s book, Tapping into The Wire: The Real Urban Crisis.

Each chapter uses a scene from The Wire to tell a story about solving public health problems: heroin addiction, teen pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases, lead paint poisoning, obesity, and gun violence.

The book candidly describes the difficulties faced by low-income city residents, such as wading through the city, state, and federal bureaucracies.

Beilenson also lined up an array of guest speakers, including David Simon, The Wire’s creator and executive producer; and alumnus Wes Moore ’01, author of The Other Wes Moore, about two men with the same name from Baltimore. One goes to Johns Hopkins and becomes a Rhodes Scholar, while the other goes to prison for murder.

Minisha Sharma was the first guest speaker. She told the class how she learned the hard way about the importance of becoming an advocate.

“When I was 22, I got hit by a car while in a cross-walk. I had $100,000 worth of bills. I had four surgeries in seven years.” And she had no health insurance.

She decided to do something about the broken health care system, so she went to medical school in her 30s.

Today she is the medical director of the Evergreen Health Cooperative, Maryland’s first nonprofit health insurance cooperative, where Beilenson is president and chief executive officer. He was previously Howard County’s health officer from 2007 to 2012.

He requires students to visit two starkly different neighborhoods and describe the differences in class papers, and he urges them not to shy away from discussing race. Some students compare Roland Park, a white, upper-class neighborhood, with Middle East, a low-income black community, while others examine the differences between Ashburton, a middle-class black neighborhood, and Pigtown, a low-income white community.

Jonathan Hettleman ’14, a political science major, took Beilenson’s class two years ago and liked it enough to come back this semester as a teaching assistant.

“We’re not just talking about the people and the neighborhoods affected by these issues, we’re going to see them,” says Hettleman.

Maria Adebayo ’14, who is majoring in international studies and sociology, is from Prince Georges County, Md., and decided to take the course this semester to learn more about Baltimore.

“It has speakers who are involved in the reality of Baltimore,” she says. As for Beilenson’s class presentations, she says, “what augments his teaching style is his experience.”

Beilenson says the students have left an impression on him for their “curiosity and ideas on how to solve seemingly intractable problems. I hope they have developed a better understanding of the complexities of urban issues and the need to devise comprehensive strategies to address the social determinants of health in a community.”