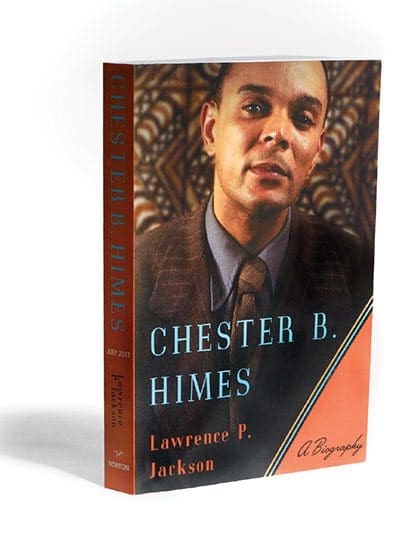

Chester Himes created Grave Digger and Coffin Ed in 1956, and he won global acclaim with a series of novels detailing their exploits. But Lawrence P. Jackson, Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of English and History, stakes a claim for Himes past his emergence as a master of detective fiction. In a new biography, Chester B. Himes, Jackson identifies Himes as a key figure in the generation of brilliant, mid-20th-century black writers that includes Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, and James Baldwin.

The new biography excavates Himes’ unsparing meditations on race, politics, and masculinity, many of which were published in the two decades before his renowned crime fiction appeared. Jackson’s close readings of these texts and access to new archival materials make a compelling case that Himes broke significant new ground in tackling issues that remain at the center of American writing.

Jackson eschews what he dubs “romantic mythicization” in favor of weaving Himes and his peers back into “the crisis of day-to-day life” faced by African-American authors writing in the mid-20th century. It was a crisis manifested in the most basic aspects of life, including, says Jackson, “the inability to get an apartment, to buy a house, to eat at a nearby restaurant, or use libraries and get access to information.”

“I am interested in making an intervention into the mainstream narrative, which excludes systematically, almost as a point of principle, black voices and black people,” says Jackson. “Especially as a biographer of African-American subjects, as an African-American self, I am always interested in providing a corrective.”

Himes felt the quotidian crisis Jackson describes even more acutely than many of his cohorts. As a young man, Himes was arrested for a bungled armed robbery in 1928 and served more than eight years in prison. Himes procured a typewriter while in the Ohio Penitentiary and began his journey as a writer there.

“Prison was a very jarring and deeply uncomfortable experience [for Himes],” says Jackson. “His ability to create a private emotional and intellectual space through writing was a key way for him to survive that experience without becoming insane.”

Himes was already selling his unsparing and candid tales of life behind bars to magazines, including Esquire, when he emerged from prison in 1936. Yet early successes offered no easy path into literary circles. Himes’ fortunes oscillated between stints at prestigious writing colonies such as Yaddo and manual labor jobs taken to make ends meet.

Himes’ growing ambitions as a writer also collided with the racism that deeply permeated America’s publishing and film industries. “As his work grew in some of its richness,” Jackson says, “it was difficult for him to get published.”

Yet Himes persisted. Two classic novels—If He Hollers Let Him Go (1945) and Lonely Crusade (1947)—joined an impressive body of stories and reportage, including what Jackson describes as “radical, sharp-edged journalism calling for absolute resistance [to racism] during the Second World War, which was a very unpopular stand.”

Himes eventually moved to Paris in the early 1950s. “I don’t think how Himes personally chafed against the abject racism in the United States at that time can be exaggerated,” says Jackson, “but there was also the sense of [American] cultural philistinism that rankled him as well.”

Himes found Paris more congenial. If He Hollers Let Him Go received a glowing mention in French psychiatrist and political theorist Frantz Fanon’s classic work, Black Skin, White Masks (1952). And Himes’ noir detective novels, published first in Paris in French translation, finally won him the wider audience in the late 1950s that he had long sought with his earlier work.

Despite the enduring appeal of Grave Digger and Coffin Ed, Jackson’s initial attraction to Himes’ story was the author’s unique stance in the era’s fraught politics. “I was drawn to Himes as a writer with political commitments,” Jackson says, “who figured out an independent path between the Communist left, and the black middle class represented by the NAACP and the Urban League.”

Chester B. Himes will certainly draw new readers to the author’s entire body of work — including early sprawling gems such as Lonely Crusade (1947), which grapples with race, labor, class, and war.

“I think that we can get a lot from Lonely Crusade in our exact political moment,” says Jackson.