A glimpse at ongoing faculty research

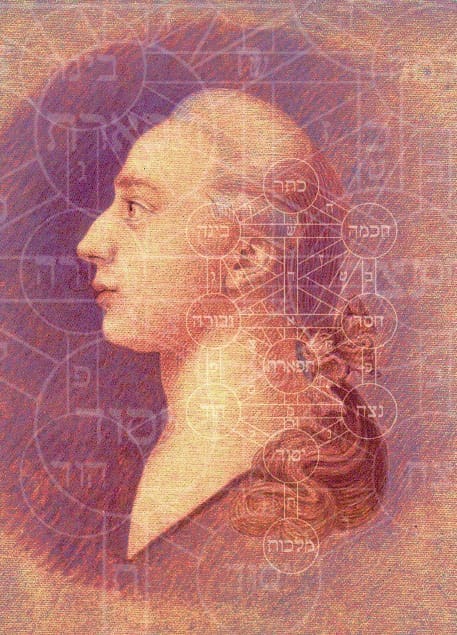

Casanova, the Kabbalah Convert?

Yet, as it turns out, once his lascivious adventures were mostly done, the 18th-century Venetian explorer turned to one aspect of Jewish spiritual thought—the Kabbalah—while exiled in Prague, according to research by Pawel Maciejko, an associate professor of history, and the Leonard and Helen R. Stulman Chair in Classical Jewish Religion, Thought, and Culture at Johns Hopkins.

Maciejko stumbled over Casanova in 2009, while he was poring over texts for a monograph he is writing on Rabbi Jonathan Eibeschütz—a heretic and “arguably the greatest rabbinical scholar of the late 18th century.”

“My main research tool is serendipity,” says Maciejko, who came to Johns Hopkins last year. “I found out that Casanova had a network of contacts in Kabbalah, and he studied Hebrew. It takes a lot of effort to learn Kabbalah, and he did that. Was he doing it to advertise himself, or make some attractive connections? Was he truly fascinated with it?”

Kabbalah, a wide body of ancient knowledge that promises to add fulfillment and meaning to its practitioners’ lives, is still taught in most Orthodox yeshivas around the world. It has also been an object of fascination for many non-Jews through the ages—including those today, when pop singer Madonna embraced it several years ago.

But Casanova, a libertine in most ways, has never been confused with someone who is pious. If he was truly transfixed by Jewish mysticism, it would place the storied adventurer in a new light.

“This wasn’t a new religion for him,” Maciejko says. “He was a radical enlightenment person. He thought religion was a path to persecution.” And perhaps understandably so, given that he had been imprisoned and then excommunicated for what Catholic Church authorities in Venice called an “affront to religion and common decency.”

Nonetheless, as he aged, he sought out Kabbalah. “It was knowledge that explained the universe—knowledge that the Jews had—or so he believed,” Maciejko says.

The scholar has been reading through Casanova’s manuscripts to learn about his Kabbalah contacts. So far, Maciejko has uncovered that the daughter, Eve, of noted Jewish heretic Jacob Frank (1726-1791) was one of them.

“Casanova mentions Kabbalah a lot, but he’s very inconsistent,” Maciejko says. “It’s clear, though, that he took the teachings very seriously.”

A Deeper Look at School Choice

Unlimited school choice has been invoked as a cure for many urban ills, including delinquency, lower educational attainment, and crushing poverty. Its ostensible powers to change the lives of the poor for the better have turned the concept of educational choice into a political football, one that gets tossed around during discussions about the funding of underperforming public schools.

But does allowing students the chance to attend the school of their choice actually result in greater access for all students in a district? Research by Julia Burdick-Will, an assistant professor of sociology with a joint appointment in the School of Education, has found that the evidence is a bit muddled, and that much of what politicians claim for the idea doesn’t resemble the truth.

For one thing, even in school districts without formal choice programs, the data show that children from poor neighborhoods are more likely than wealthy students to travel miles to school—a finding that contradicts claims made by school choice advocates that needy children are deprived of options.

Alternatively, even if there are programs designed to increase access to other schools, would-be students may not be able to get there easily.

A study Burdick-Will is conducting with Marc Stein, an associate professor of sociology at the School of Education, looks at how the geographic distribution of schools in Baltimore City, where all public schools are virtually available to anyone, relates to access to quality education.

They created a database to estimate the time it takes each Baltimore student to walk or bus to school. They learned that it is easier for kids in East Baltimore to travel to higher-quality schools outside their neighborhoods than it is for those who live in West Baltimore, in part because of large geographic obstacles in the city’s west side that transportation systems must circumnavigate.

“This doesn’t mean that no one in West Baltimore gets out, just that doing so takes additional time, planning, and stress that likely impacts how they feel when they get to the classroom,” Burdick-Will says.

“We need to document the pattern and see how they’re figuring this out and find ways to support them.”

Conjuring New Ideas on Gravity

Among the phenomena of the universe that have most vexed theoretical physicists, quantum gravity remains a force all its own.

Scientists have largely relied on two frameworks—Einstein’s general theory of relativity and quantum field theory—to try and understand how the universe works. While these two methods help scientists explore some of the deepest laws of nature, in tandem they fail miserably in providing a full explanation of the role quantum gravity plays in them.

But what if there were enough commonalities within these two frameworks to allow scientists to develop new ideas on the mysteries of the ages, including ones in which gravity plays a starring role, such as the initial conditions of the universe, the nature of the Big Bang, and the interior of black holes?

Holography, a field developed within the past two decades, gives scientists the tools to figure out the commonalities between general relativity and a quantum theory of gravity.

“The holographic principle is one of the major, relatively recent discoveries in theoretical physics,” says Ibrahima Bah, an assistant professor of physics. “This discovery is as important to the understanding of gravity as curvature of space-time in general relativity.”

Quantum field theory allows us to understand the basic building blocks of matter, such as electrons and quarks, as well as fundamental forces, such as electromagnetism, Bah explains. Meanwhile, general relativity helps scientists work to understand gravity, the dynamics of planets, stars, galaxies, and the large-scale structures of the universe.

Those who work with holography build models of these two frameworks to see how long-known common points might direct them to new answers.

Bah’s research involves utilizing the all-purpose Swiss Army knife of theoretical physics—math—to note equivalency, something known as the Maldacena conjecture, which was first posited in 1997.

“The fact that these two frameworks can contain the same answers,” Bah says, “and this idea that holography may explain gravity, is revolutionary.”