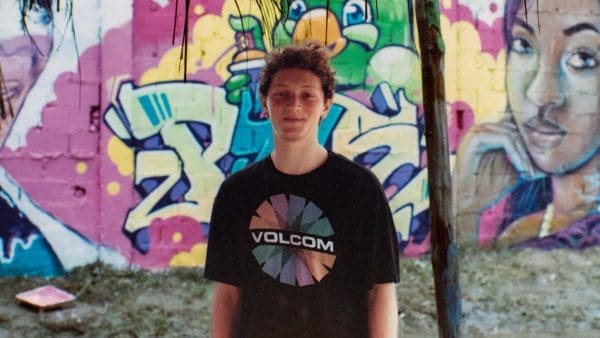

Mike Tritsch remembers exactly when he became obsessed with ancient Egypt. In his elementary school library in the first grade, he came upon a book about the lost civilization. “It was one of those books with clear pages that lets you peel back the layers to see into various structures, and I was entranced and wanted to know more about this ancient culture,” Tritsch recalls.

Having been fascinated for so long, imagine how the sophomore—a Woodrow Wilson Fellow double-majoring in archaeology and Near Eastern studies—felt over winter intersession when he found himself in Luxor, standing before the Temple of Mut. Tritsch traveled to Egypt with Betsy Bryan, the Alexander Badawy Professor in Egyptian Art and Archaeology and the Krieger School’s vice dean for humanities and social sciences, and her team to assist with the excavations she’s been doing at the site for close to 20 years. “It was incredible—10 times better than anything you’ll ever see in a book,” he says.

Much of Bryan’s research has been to gain an understanding of how this area was utilized in the first and second millennium BCE and the rituals performed there in relation to the namesake goddess Mut. Tritsch spent the month excavating an area outside the temple walls at the possible site of a domestic dwelling of a priest, or perhaps a craftsman, associated with the temple. Analyzing the findings will help the team make a more nuanced assessment.

“We found a large array of pottery sherds, stone tools for polishing and maybe cutting, a good number of animal bones, and some agate, possibly used for tools or for some kind of cultic purposes,” Tritsch says. One of the more fascinating things to come out of the ground was a blue scaraboid bead bearing the image of a king holding a crook and standing on two uraei (reared cobras). But the more mundane finds—such as the large amount of red and white painted mud brick, which may have been used for furniture, covering of walls, or fresco scenes—might actually be more useful for Tritsch in interpreting the site.

“We’re still in the interpretation phase, so I’m going to be working with the bricks to determine their exact use—basically comparing the painted surfaces found at Mut Temple to those found at other sites of relatively contemporaneous time periods throughout Egypt and Sudan, as well as to tomb paintings from this era to see if any of the scenes display evidence of the use of painted mud brick,” he says.

Tritsch, who has also done archaeological work around the state of Maryland in conjunction with the Smithsonian, will excavate in Israel as the JHU/AIAR Undergraduate Archaeological Fellow this summer. He plans to return to the Temple of Mut during the next two intersessions to further his research. “It’s touching people’s lives from 3,000 years ago,” he says.