Neuroscience might generally be considered a contemporary field probing the frontiers of our understanding of the human brain and, as such, not an academic arena concerned with the thoughts of 17th-century philosophers, such as John Locke. But senior neuroscience major Brianna Aheimer says the English thinker’s ideas do come up in her classes.

“A lot of the background of cognitive science really started with philosophy,” she says. That’s because some questions about how humans learn are evergreen and unanswered. Locke, for instance, argued that concepts could only be learned through first-person experience. Aheimer was inspired to test this assumption. She has been working in Assistant Professor Marina Bedny’s neuroplasticity and development lab that focuses on comparing congenitally blind and sighted individuals. She mentions Locke’s philosophical position in the proposal for the Provost’s Undergraduate Research Award she was given for a project titled “Learning About Color in the Absence of Vision: A Training Study with Blind Individuals.”

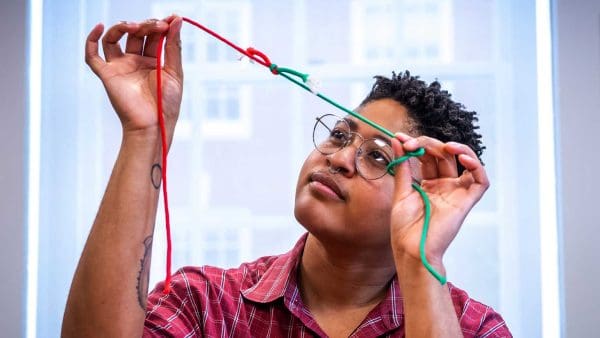

Locke would have to agree that blind people can never experience colors—but then how do they learn about them? Aheimer, working with PhD student Judy Kim, is building on an earlier experiment in the Bedny lab wherein blind and sighted individuals were asked to sort common animals according to various parameters, such as shape, size, texture, and also, color. Blind participants performed the task with far less accuracy, particularly in regard to color. One possible reason for this is that while blind individuals might have heard or read that polar bears are white and elephants are gray, that understanding was not reinforced by having repeatedly seen imagery of these animals as sighted people have. Another explanation is simply that blind people might not have many reasons to learn about color—they don’t have to know that limes are green and that lemons are yellow to pick them out at the grocery store.

Aheimer’s research aims to level the playing field, so to speak, and create a study where sighted and blind individuals have the “same opportunities” and “same motivations” to learn about creatures and their colors. But how to do that? “We don’t want to rely on animals that are already known about,” she says. “So, I think at the moment we are leaning toward creating magical creatures on a different planet.”

Participants will read stories about mythical, other-worldly animals that include various levels of descriptive information about them. Next, they will be quizzed about the animals and their color. She’s still developing just how the study will be structured. “Sometimes I think I should be asking my brother for help,” Aheimer says. “He’s into playing Dungeons and Dragons.”