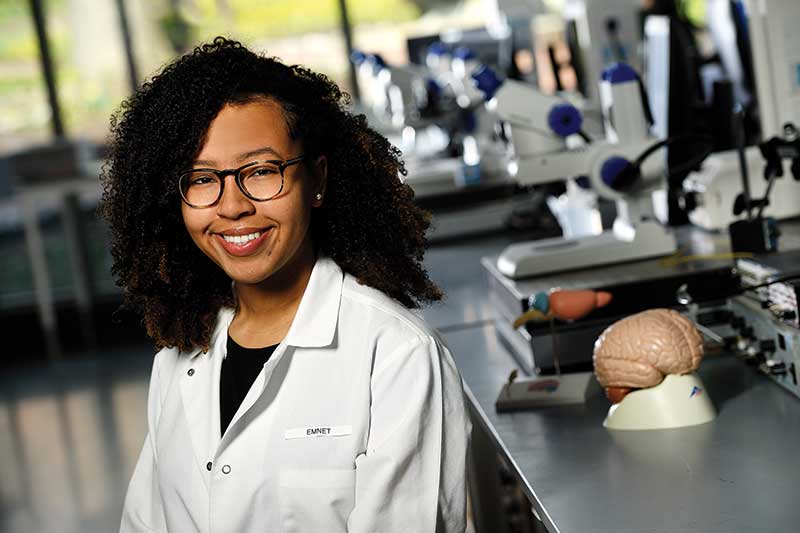

Since last summer, junior Emnet Atlabachew has been busy working in Associate Professor Shilpa Kadam’s lab at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, investigating the mechanisms underlying epilepsy in neurological disorders.

Atlabachew’s exacting work requires great concentration, such as when using a cryostat machine to section out tiny samples of biological material at subzero temperatures. As she works, her family is never far from her mind. That is because a close relative suffered from epilepsy and that loved one’s seizures were a troubling part of Atlabachew’s girlhood.

“I would be very frustrated with doctors because they would never have an answer to anything,” Atlabachew recalls. “Going into undergrad, I wanted to know more about the brain and also I knew that I wanted to focus on epilepsy.”

The neuroscience major’s lab work is part of an Albstein Research Scholarship awarded last year. Her specific project involves measuring the density of parvalbumin-positive interneurons in brains from a mouse model of genetic epilepsy. (Parvalbumin is an important intraneuron protein, and scientists believe parvalbumin-positive interneurons may play a significant role in epilepsy but that role needs to be better understood.) She uses the cryostat to make very thin slices of the brains only 14 micrometers thick—much thinner than a human hair—and mounts them on slides, which are then stained with antibodies to highlight and identify certain neurons.

“After the staining, I put them in an apotome, which is just basically an amazing version of a microscope allowing you to actually see the neurons,” she says. Photos are taken and a software program aids Atlabachew in counting the neurons containing parvalbumin. The project is ongoing, but she will be comparing counts with control brains that were not modified. “We want to see if there’s a difference in the density of parvalbumin between the two, and also any differences in density among different areas of the brain,” Atlabachew says.

As part of her award, she attended an annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society in New Orleans, which brings together the field’s leading researchers for lectures, conferences, and networking. “It was kind of intimidating to go there because I didn’t see any other undergraduates—it was mostly PhDs, MDs, and postgrads,” she says. “But they were very welcoming, and it was really an amazing experience for me.”

When not boning up on how the brain works, Atlabachew challenges her own brain with a different type of thinking: a minor in Africana Studies. As the daughter of Ethiopian immigrants, the subject interests her. “Because I’m so top-heavy with science courses,” she says, “I also wanted to do something a bit different.”