Conducting scientific research at sea is challenging—you’re isolated, subject to rough weather, and must rely solely on the supplies and equipment on board. Conducting scientific research at sea on a 134-foot brigantine, a type of two-masted sailing ship, is even more challenging. But it can also be a grand adventure.

Senior Cecilia Howard discovered this last spring after spending nearly six weeks aboard the Corwith Cramer, a research brigantine operated by the Sea Education Association (SEA), a nonprofit institute based in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. Howard, who is double majoring in molecular and cellular biology and Earth and planetary sciences, participated in SEA’s semester-long Marine Biodiversity and Conservation program. In addition to her time sailing from Key West to New York City (by way of Bermuda), there were also projects and coursework on ocean-focused public policy. After completing the program, she participated in a United Nations panel discussion on high-seas biodiversity. “It was probably the hardest workload I’ve ever had but it was also some of the most rewarding work I’ve done,” Howard says.

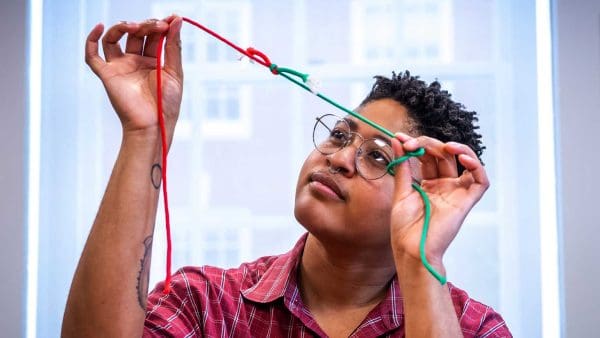

While at sea, all students engage in daily data collection, testing the waters for temperature, salinity, and zooplankton diversity, among other things. There are also group projects, and Howard’s focused on Sargassum, a type of floating seaweed. In the open ocean, it creates vital ecosystems, providing food and shelter for all types of animals. For a few years now, however, thick masses of it have been coming ashore in the Caribbean and fouling beaches. Howard’s work involved determining if genetically morphed versions of the plant were to blame and where they may have originated. First, she used a dip net to scoop up seaweed samples.

“We had a whole molecular biology lab onboard the ship, and we would extract DNA and use what’s called a polymerase chain reaction process to amplify genes,” Howard says. “And once we got back to shore, we sent them out to be sequenced and then did a variety of analyses of those sequences to compare the genetic relations between different forms of Sargassum.”

Of course, 35 students and crew living in cramped quarters presented some social lessons. “It really helps learning how to collaborate and get along with everyone,” Howard says. Students take six-hour watch shifts, which sometimes meant the day started at 12:30 in the morning. And on one occasion, Howard’s watch had her scrambling 50 feet up into the rigging. “It was terrifying but so much fun because the entire boat is moving underneath you as you look out on the vast empty ocean around you,” she says.