Junior Sarah Elbasheer is a medicine, science, and humanities major drawn to exploring the history of science—especially going beyond the conventional narratives sometimes encountered in the field. “There is a tendency to skip over other cultures and draw a straight line between ancient Greece and the Renaissance in Europe,” she says.

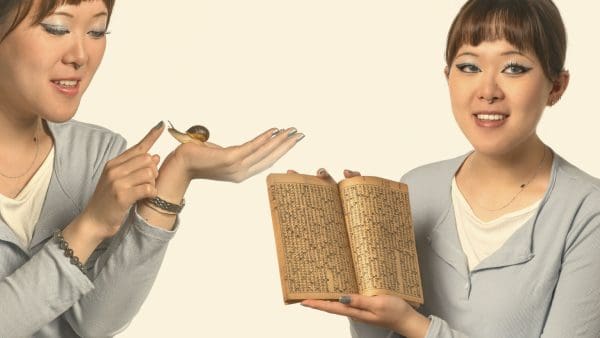

This approach slights Asian and Middle Eastern contributions to science and medicine, she notes, and also instances where these worlds collided, such as in the Tānsūqnāma, a 1313 Persian (modern-day Iranian) manuscript, which translates as The Treasure Book of the Ilkhans on the Chinese Arts and Sciences. Originally in four volumes, only one survives and it is secured in an Istanbul library. Working from scans, Elbasheer is focusing on the half of the volume that contains Persian translations of Chinese “pulse medicine,” a diagnostic system interpreting the strength and rhythms of the pulse. (Elbasheer notes that you can still find practitioners of this traditional medicine in China and India.)

Pulse medicine is composed in rhyme. It’s medical poetry. “It is written that way to help medical students to remember the diagnostic techniques,” Elbasheer explains.

This mnemonic scheme was part of the original Chinese text. But if anything is bound to get lost in the translation between entirely different languages, it’s rhyme. For instance, in a Latin translation of these same Chinese poetic pulse diagnostics, all the medical information is conveyed in the new language, but the rhymes from the original Chinese are gone.

Persian polymath Rashid al-Din, credited with compiling the Persian version, took a different approach. “He takes advantage of a shared tradition in both China and Persia for rhymes used in medical education,” Elbasheer says. “What we see is this attempt to preserve the sound of the poetic performance, creating an entirely new linguistic system to preserve the sound of the verses. So, basically, it is trying to connect the tradition in Persia about the emphasis and importance of oral performance and didactic poetry to the effort of preserving the verses.”

Elbasheer’s ongoing analysis of this ancient bilingual, bicultural work will likely be the subject of her senior thesis. She finds it to be a fascinating example of medical concepts moving west along the Silk Road coupled with an intricate linguistic solution to preserving both their sound and science for a new culture. With apologies to Rashid al-Din, she admires the Persian version after the conversion.