The chances of becoming seriously ill or dying from COVID-19 increase with age, with senior citizens at the greatest risk. Young adults, though not immune to the disease’s worst, are more likely to have mild cases—sometimes with no symptoms at all. What young people are at risk of doing is spreading COVID-19, which makes the importance of contact tracing—the ability to quickly and thoroughly identify and reach out to people an infected individual encountered—all the more important. Fortunately, most young people have a powerful tool to help with this in their pockets: a smartphone.

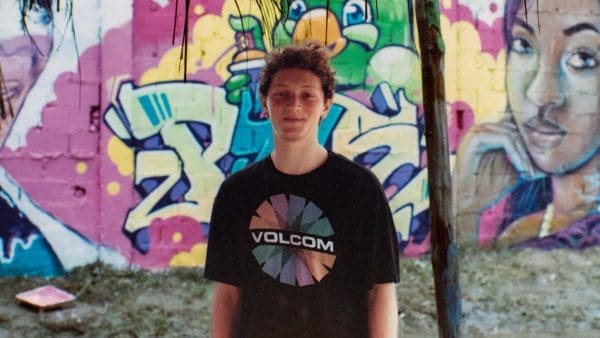

But how willing are they to engage in phone-based “digital contact tracing” to curb the pandemic? To find out, sophomore Lauren Maytin helped develop a survey given to more than 500 people ages 18 to 24 last summer. She was lead author for the resulting article, “Attitudes and Perceptions Toward COVID-19 Digital Surveillance: Survey of Young Adults in the United States,” published in the January issue of Journal of Medical Internet Research. The survey was a COVID-19-forced pivot from what was supposed to have been an in-person internship at a health care consultancy. Instead, Maytin worked remotely with the consultancy on this urgent topic.

“I was thrilled to be able to do something to help,” says the behavioral biology major. “There wasn’t much information available about this demographic at a time when everyone was trying to figure out if we were going back to campus, or kids back to school.”

And the results surprised her. While some three-quarters of the demographically diverse young respondents (compiled using the online survey company SurveyMonkey) believed COVID-19 was a public health crisis, there was significant reluctance to participate in digital contact tracing. Fewer than half indicated a willingness to “actively” participate (meaning they’d be willing to manually enter data into their phones, such as any symptoms they were experiencing). Barely a third were willing to “passively” participate—allowing their phone to track their movements. Such lackluster interest may highlight the need for more education about the importance of contact tracing.

“I was surprised because there’s such widespread use of social media and websites and apps that track your activity anyway, like Snapchat or any of the map and navigation apps,” Maytin says. “If you can track your friends in a social setting, that’s fine. But if someone’s asking you to be tracked for public health purposes, suddenly it’s an invasion of privacy?”