Is it possible to perceive the impossible? The answer is a resounding “yes!” from Isabel Won, a psychology and cognitive science double major who graduated in May. She spent most of her years at Hopkins as a research assistant in the Perception and Mind Laboratory led by psychological and brain sciences Assistant Professor Chaz Firestone.

Seeing the impossible is pretty common. Artists are adept at creating optical illusions by manipulating shading and perspective to create 2D depictions of impossible 3D objects or places—think famed Dutch illustrator M.C. Escher and his staircases doubling back on themselves in endless loops. But Won wondered if other senses could perceive the impossible. “There weren’t really many studies on illusions that aren’t primarily visual,” she says.

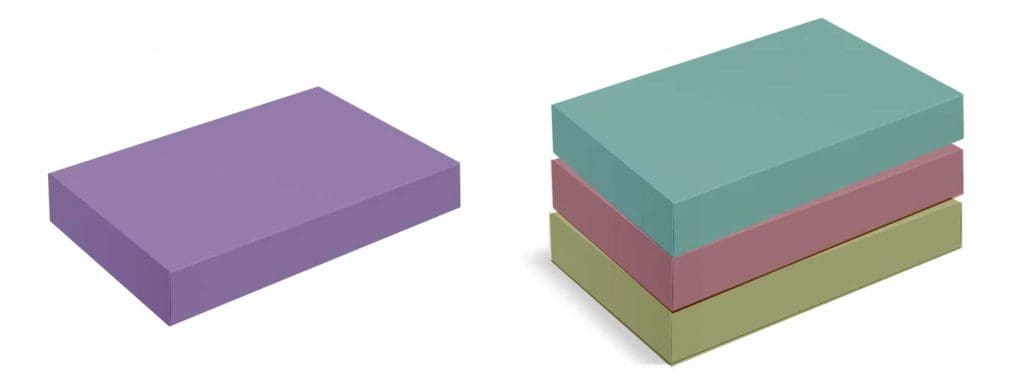

One classic example that is widely known involves a size-weight illusion wherein people are presented with two objects of different size but identical weight. When asked to lift both objects, a majority of people perceive that the smaller object is heavier than the larger one.

Weight and Illusion

Won took this concept into the impossible zone with an experiment involving three identically sized plastic boxes. Two boxes are empty and weigh the same, and one has a metal weight mounted within it. Participants are asked to lift the three boxes together and then the weighted box by itself.

The kicker? Some 90 percent of the participants she tested perceived the single box as being heavier than all three together.

“I tested it out with students on campus—just sitting in front of different buildings and calling people over to participate,” Won says.

It was a ton of fun and everybody was extremely intrigued and fascinated by how convincing this illusion was.”

— Isabel Won

A skeptical Won tried the experiment herself and also experienced the illogical sensation. “Even knowing that it was an illusion and it was impossible, I still felt it strongly every single time I experienced the experiment myself,” she says.

Won says the sensation violates a traditional thought process known as Bayesian reasoning. In essence, it says that when our minds confront ambiguous information, we are attracted toward what we already know. In this case, our brains tell us that an object lifted together with two others is certainly going to weigh more than the single object by itself.

The results of her weighty project were published in the July issue of the cognitive science journal Open Mind. “My takeaway is that our mind is able to process super impossible illusions in ways that we didn’t really expect previously,” she says.