Descartes famously remarked, “I think, therefore I am.” He still would have been onto something, however, if he’d alternatively suggested, “I speak, therefore I am.” The evolution of speech, the most complex form of communication among all animals, is a distinguishing feature of our species. Yet the connections between the development of our sophisticated vocalizations and our higher-order cognition remain poorly understood.

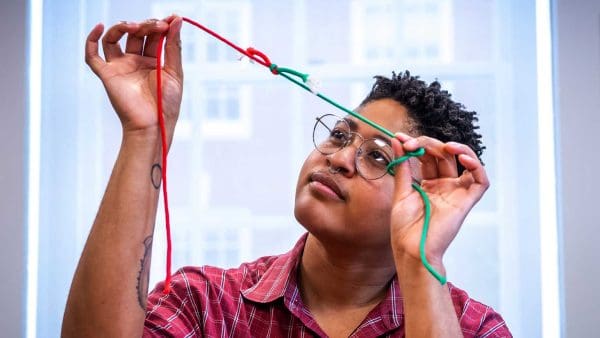

Junior behavioral biology major Jessica Dure has started a project to better reveal how communicative capabilities affect brain organization and evolution toward more advanced thinking. She is studying these linkages in Melopsittacus parrots, formally known as budgerigars and nicknamed budgies or parakeets. Popular as pets, these fetchingly colored birds exhibit a rich vocal range and can mimic human speech.

Do face muscles impact how your brain evolves?

Dure’s work has focused on characterizing the elaborate musculature used by these parrots to form their vocalizations. Additional stages of her project involve mapping the musculature of birds with other kinds of vocalization skills. For example, non-parrot songbirds, which have lesser motor control and more limited vocal manipulation abilities than parrots. Yet they possess rich song repertoires nonetheless.

We’re seeing how communication affects the brain and how musculature affects the evolution of different areas of the brain.”

—Jessica Dure, behavioral biology major

Dure came up with the project with her advisor, Amy Balanoff, an assistant research professor in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences. Balanoff had access to computerized tomography scans of parrots’ skulls that show the hyoid bone. The bone is a key structure in the neck supporting the tongue and other muscles involved in sound generation.

“My advisor gave me the freedom to come up with an idea of what we could do with these scans, and we decided to label the musculature around the hyoid bone,” says Dure.

Monitoring the data

The labeling work is time-consuming and intricate as it requires poring over dozens of grayscale scans. Each scan represents a thin slice of the parrot’s anatomy. Overall, the research is building a detailed, three-dimensional view of the area where avian vocalizations are largely produced. It’s is also a critical area for human speech.

The eventual goal is to compare the musculature maps to brain structure. One expectation, Dure says, is that there could be differences in the hypoglossal nucleus, the part of the brainstem that controls tongue movement.

Other students are now continuing Dure’s work as she prepares to go to veterinary school. Veterinary medicine is ideal, Dure says. Not only because of her lifelong interest in animal welfare, but also for the chance to collaborate with her fellow Homo sapien. Just like she did on her undergraduate research project.