Infants in low-income settings around the globe sometimes fall into a vicious cycle of malnutrition and infection. Lack of access to nutrients causes malnourishment, which leaves the babies more prone to infection, which makes it harder for them to digest nutrients, and so on.

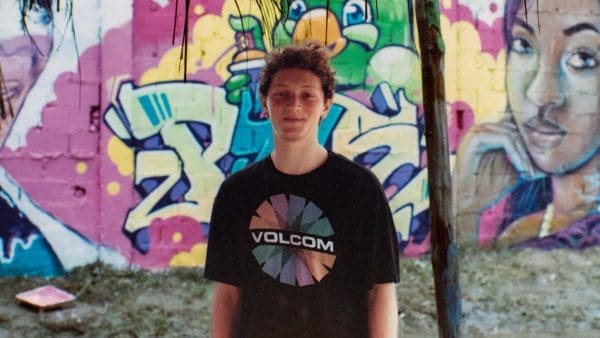

Global health initiatives often target the infection side of the cycle, using mosquito nets or antibiotics, for example. But Noah Trudeau, a junior from Detroit, is part of a research project trialing a two-pronged approach: at birth, infants in rural Bangladesh will receive a biofortified protein supplement paired with an antibiotic.

“We’re tackling it from the nutrition perspective,” Trudeau says. “How can we make sure that these children are not only getting the nutrients they need, but retaining them?”

Health Meets Social Sciences

Trudeau, who is majoring in medicine, science, and the humanities and minoring in French, arrived at Hopkins interested in health and medicine, and quickly developed a passion for the social sciences as well. He finds that global health offers the perfect combination. Hoping to put his interests into practice, he emailed a handful of Hopkins faculty in the field, eventually connecting with Amanda Palmer, assistant professor in the Department of International Health at the Bloomberg School of Public Health.

So far, Trudeau’s role in Palmer’s project has been at the safety profile stage, helping to determine that the antibiotic is safe and effective before coupling it with the protein supplement. He analyzed demographic data for groups of infants who received the antibiotic versus a placebo, ensuring they were relatively similar. He also organized data into tables on pre- and post-dosing symptoms like diarrhea and cough, and is helping Palmer draft the project’s first paper, which they hope to publish soon.

“The general takeaway is that not only are the adverse events infrequent, but they’re notably minor. So, it looks promising,” Trudeau says.

Engaging Families and Communities

There are takeaways for Trudeau personally as well: a refining of his insights into global health and the way it affects people not only in hospitals and clinics, but right where they live.

“This experience has taught me to approach global health differently: not just from a biomedical perspective, but also from the social science and humanistic side,” he says. “Global health really isn’t just about medicine; it’s about how can we engage families and patients to better serve these communities. And how can we make not only long-lasting change, but equitable change. Decolonizing global health is one of my main interests—this field has been rooted in the idea that health is this fundamental right, but only for those who can afford it. Because I believe wholeheartedly that health should be a right regardless of where you live.”

“Global health is not just policymaking and research,” says Trudeau. “It’s imagining the lived experiences of people who are going to be affected by that policy.”