In work that may deepen our understanding of Alzheimer’s disease and similar disorders in humans, Johns Hopkins neuroscientists working with rats have pinpointed a mechanism in the brain responsible for a common type of age-related memory loss.

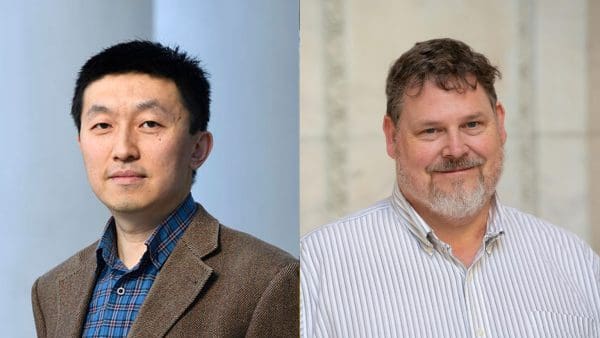

“We’re trying to understand normal memory and why a part of the brain called the hippocampus is so critical for normal memory. But also with many memory disorders, something is going wrong with this area,” says senior author James Knierim, a professor in the Zanvyl Krieger Mind/Brain Institute, whose Hopkins team reported its findings recently in Current Biology.

Neuroscientists know that neurons in the hippocampus, located deep in the brain’s temporal lobe, are responsible for a complementary pair of memory functions called pattern separation and pattern completion. These functions occur in a gradient across a tiny region of the hippocampus called CA3.

Balance in Brain Patterns

In normal brains, pattern separation and pattern completion work hand-in-hand to sort and make sense of perceptions and experiences, from the most basic to the highly complex. If you visit a restaurant with your family and a month later you visit the same restaurant with friends, you should be able to recognize that it was the same restaurant, even though some details have changed—this is pattern completion. But you also need to remember which conversation happened when, so you do not confuse the two experiences—this is pattern separation.

When those functions swing out of balance, memory becomes impaired, causing symptoms like forgetfulness or repeating oneself. The Johns Hopkins team discovered that as the brain ages, this imbalance may be caused by the CA3 gradient disappearing; the pattern separation function fades away, and the pattern completion function takes over.

In the restaurant example, your brain may focus on the common experience of the restaurant to the exclusion of the details of the separate visits, leading you to remember a conversation that took place during one visit, but mistake who was talking. “We all make these mistakes, but they just tend to get worse with aging,” says Knierim.

Pinpointing the memory loss mechanism could lay the groundwork for learning what prevents memory impairment in some humans, and therefore how to prevent or delay cognitive decline in the elderly, the researchers say.