Prisons across the country offer opportunities like 12-step programs and GED or college classes, and incarcerated people often try to take advantage of them. But more frequently than most people realize, those efforts are stymied by guards wielding spontaneous rules that prevent the incarcerated from attending, or mysterious rosters that don’t include their names.

“I was no longer the biggest obstacle to changing my behavior. The barriers erected by prison officials—inane rules, long waiting lists, hassles, and humiliations from abusive guards—became my greatest challenge,” Dean Faiello wrote in an essay while incarcerated in the Attica Correctional Facility in New York.

An Important Collection

Faiello’s essay is one of 3,300 that make up the American Prison Writing Archive, an open-source digital collection of firsthand testimony by people incarcerated around the U.S. The archive is in the process of moving from Hamilton College, where it was founded, to Johns Hopkins, where it will grow and serve as a resource for anyone interested in learning more about life in the carceral system.

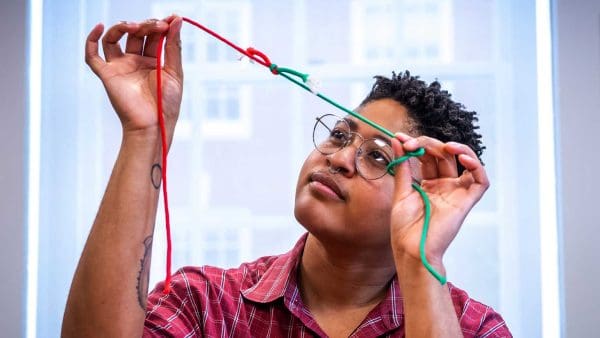

Adriana Orduña ’23 is one of several Hopkins scholars already delving into the archive. She recently spent two semesters reading and reviewing the essays to understand how guards and other officials use hierarchy, rules, and regulation to control incarcerated people, and the harm this “bureaucratic violence” causes. Orduña found that the practice of this unsanctioned punishment, which comes on top of the official sentence, is prevalent, serving as a devastating—and little known—element of incarceration.

“Guards want to exact their own version of justice. They think that people in prison deserve to be punished. So they create these additional punishments all the time,” says Orduña, who is majoring in international studies and sociology.

Police and Prisons

Always interested in social justice, Orduña took a 2020 course with Stuart Schrader, an associate research professor in the Department of Sociology and the Center for Africana Studies, on police and prisons. When Schrader emailed students a year later with an offer to join a research project involving the archive, Orduña jumped at the chance to go beyond the theory she had learned in class.

Once she landed on the topic of bureaucratic violence, Orduña—who hails from New York— narrowed her focus to upstate New York, reading and analyzing 170 essays. She found them both upsetting and compelling. She often rose early to read another set before class, and eventually produced an academic paper on her findings. In October, Orduña and two other undergraduate researchers presented their papers at a panel about the archive.

“It’s really different to read essays written by scholars versus reading letters from people who are experiencing prison every day,” she says. “The incarcerated authors have a lot to say about what’s going on inside, and they often have really in-depth analyses.”

The American Prison Writing Archive is currently housed at Hamilton College in New York. The archive is scheduled to be moved to Johns Hopkins by December 31, 2022. It will be housed at the Sheridan Libraries.