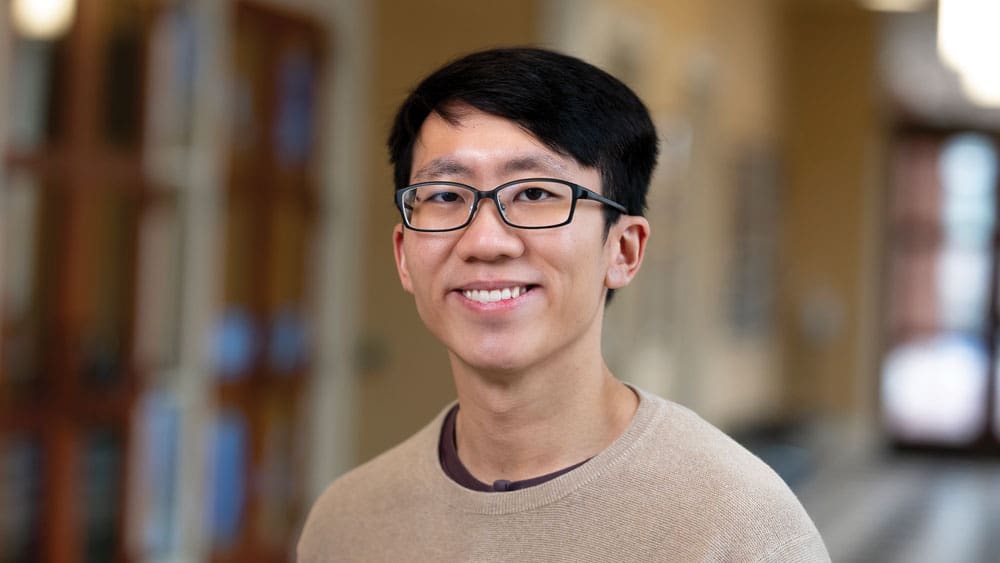

It’s a common refrain that food brings people together. Baltimore’s Chinese community has historically gathered at restaurants, but not just for dinner. According to junior Ethan Tan’s research, Baltimore’s Chinese restaurants have provided immigration help, income, job training, community, and even housing for new Chinese immigrants to the United States.

“It was an amazing network of a safety net, almost of stability, and enabling further actions like mobility across the United States, and just allowing them to look for opportunities in ways that they would not have been able to without that kind of support,” Tan says.

Seeds of an idea

The idea for the research grew out of assistant history professor H. Yumi Kim’s class History Research Lab: Asian Diaspora in Baltimore. There are not a lot of books or archives focused on Baltimore’s small and geographically disparate Chinese community. To supplement readings, Kim invited community members to share their personal perspectives. Tan, a history and medicine, science, and the humanities double major, was intrigued by the conversations, and kept interviewing community members after the class ended. The core of his research is first-person stories he’s gathered about living and working in Baltimore throughout the 1900s, often at restaurants like the White Rice Inn in Chinatown or the New China Inn in Old Goucher.

Those stories are tied to changing 20th-century immigration laws that often barred Chinese immigrants entirely. At some points in the early 1900s, Chinese restaurateurs were classed as merchants and could sponsor future employees. This meant they were the only part of the community aside from American citizens able to get paperwork for new immigrants. Sometimes workers lived at the restaurant until they could find or afford a place of their own.

Expanding opportunities

Restaurants also served as “incubators” for would-be restaurateurs. One of the narratives that Tan traces was that of Robert Chin, who arrived from China in 1951. His first stop was his uncle’s downtown Baltimore restaurant, the Golden Pheasant, where he also lived briefly. He worked as a waiter, then a cook, at multiple restaurants owned by family members, and eventually opened his own carryout business. The restaurants gave immigrants the ability to grow where they landed: opening businesses, taking on roles like police officers or community organizers, and starting their own families, Tan found.

“It was a much lower-risk option to learn to work in the restaurant first and then simply replicate everything that they had experienced and been trained in,” Tan says.

This research has been a learning experience for Tan on the value of community-based collaboration and research. The Chinese community in Baltimore is an underrepresented area of history, he says, and he has much more to learn. He plans to investigate the importance of other social organizations, like churches and sports leagues (fast-pitch softball was big locally) while completing his BA/MA history degree. But his main goal is to serve the community by giving members the opportunity to share their stories and see the value in their own histories.

“There is an aspect of empathy that I believe is part of the job description of a historian,” he says.