Historic Supreme Court rulings dominate the pages of newspapers and U.S history textbooks. It’s not those individual rulings that matter in Kory Gaines’ research, but when and how the court rulings impacted American citizens and democracy. “We’re thinking about how the court is a policymaker, in a way,” he says. “Is the court a democratizing force? Or is it an anti-democratic power broker?”

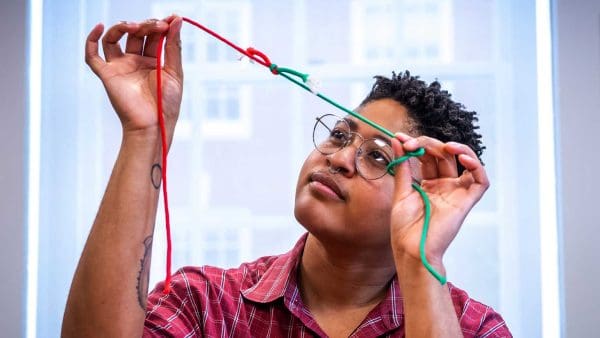

Gaines, a fourth-year political science PhD student, is analyzing the federal government’s role in civil rights and racial justice with Robert Lieberman, Krieger-Eisenhower Professor of Political Science, and Desmond King of Oxford University. According to Lieberman, understanding what made the expansion of civil rights and the extension of democracy possible between 1840 and today could help make future progress toward “racial democratization” easier.

Creating a new database

To examine those conditions more closely, Gaines created a new database by compiling hundreds of minority rights-related laws, Supreme Court cases, and executive actions. Then he drilled down to more than 200 Supreme Court rulings and coded them for positive or negative civil rights outcomes. The analysis of those rulings (recently published in Law & Policy) found that the Supreme Court was often ahead of Congress and the president in making strides toward a more equitable country. But rulings alone weren’t enough to create change. The data show that the Court sometimes ruled repeatedly on the same issues, such as housing discrimination, until other branches were pushed to enforce the decision.

“The most interesting part of the paper is when legislators don’t want to decide on a policy because it’s touchy,” Gaines says. “When they don’t want to pass a law, they leave the discretion up to the Court to make a decision.”

The Court can use its power to set civil rights standards, but it takes repeated efforts and cooperation from, and enforcement by, Congress and executives to make those rights real. Gaines says the research also highlights the potential of the impact of political organizing. Labor rights and civil rights groups began working together in the early 20th century. That cooperation may have resulted in the increase in pro-civil rights Supreme Court rulings in the early 20th century—decades before the civil rights movement.

“This research is important in 2024 because we still need to think about the varying levers for democratization [to] expand the political rights and powers of all people,” he says.

Next steps

Gaines’ research with Lieberman will be used for several upcoming papers and a book project. Gaines will also use similar methods and literature to build out his work on political science and Black history, such as how events like police raids on blues nightclubs changed American politics and impacted political organizing. This is why he was drawn to Lieberman’s research project in the first place, he says. It’s the part of political science that brings history in.