The 1960s were a pivotal time in American history. The Civil Rights Movement, the Vietnam War, and the War on Poverty were just a few of the major social, political, and cultural events of that period. Big changes were also occurring within the Catholic Church.

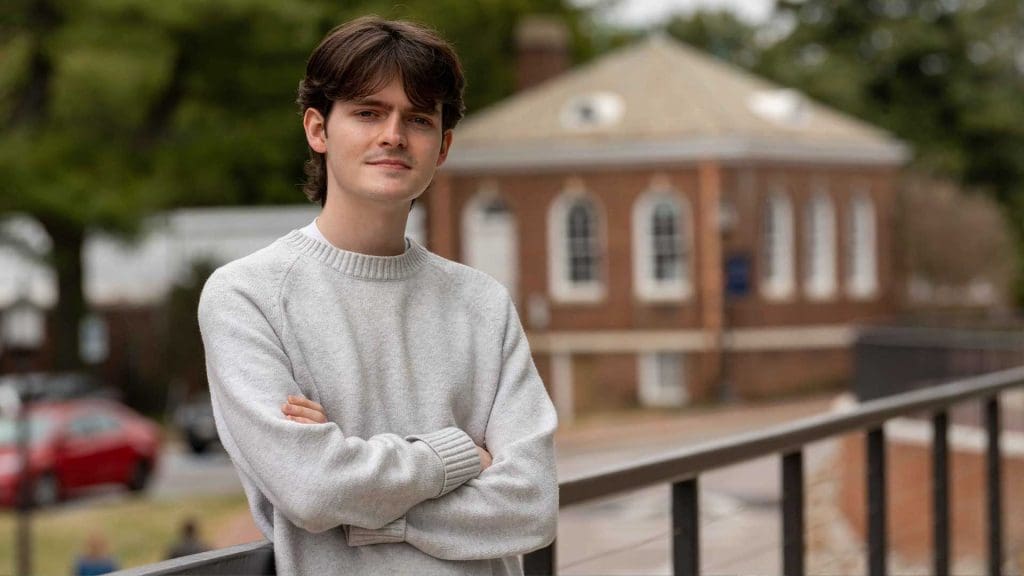

History major John Ellis ’25, co-president of the Undergraduate History Association, is exploring how college students experienced this time of change by digging into the archives at two nearby Jesuit institutions: Loyola University Maryland, and Georgetown University in Washington, D.C.

How religion can change conclusions

Ellis grew up going to Catholic schools in eastern Massachusetts. In high school, he completed a project on French theologian and social activist Peter Maurin, who helped spearhead the Catholic Worker Movement during the Great Depression.

“That was the first time I realized that people of the same religious identity can come to very different conclusions about what the world should look like,” says Ellis.

Histories of the Catholic Church tend to focus on the Pope, bishops, and clergy, he notes. “I was interested in knowing the student perspective.”

In addition to other world events, the 1960s were also a significant time for Catholics. Vatican II (1962–65) was the first ecumenical council to include women. It ushered in major changes for the church, including that Mass no longer had to be conducted in Latin. “People have written about how [Vatican II] changed how they view God and the role of religion in their lives,” says Ellis. “It empowered laypeople to be more critical of the church … and more open in their own view of religion.”

Ellis thought Catholic college students in the 1960s would have especially forward-thinking ideas. “Universities foster a level of critical thinking and also an independence that allows students to be a little more open and more bold in ways that people in the church might not have felt as empowered to do,” he says.

The value of physical archives

In the Loyola and Georgetown archives, Ellis had some interesting finds. Among the student newspapers, literary magazines, and handbooks, he discovered a lemon preserved in acrylic. The fruit was part of a “lemonstration” organized by Georgetown students in 1973 to protest proposed increases in tuition and board. Students piled about 6,000 lemons against the door to the president’s office during a board of directors meeting. Ellis also found the notes from a 1967 Jesuit Honor Society meeting at Loyola. In general, he found that most students who were writing about the changes in the Catholic Church embraced the more democratic, inclusive approach of post-Vatican II, and were more critical of church authority and hierarchy.

Ellis intentionally chose a thesis that would involve analog research. Looking at historic documents in person is a very different experience, he notes. “It allows you to really get in the shoes of the people you’re reading about, in a way that I don’t think online research does.”