When the Johns Hopkins Archaeological Museum officially reopens on October 13, it will celebrate both 140-plus years of existence, and a new chapter in its life as a teaching collection for the university community.

“I’ve long thought that the Archaeological Museum is one of the jewels of a Hopkins education,” says Emily S.K. Anderson, associate professor in the Department of Classics, who was named the museum’s director on July 1, 2025. Anderson takes the reins from long-time director Betsy M. Bryan, Alexander Badawy Professor Emerita of Egyptian Art and Archaeology.

Since it opened its doors 143 years ago on Hopkins’ then-downtown campus, the museum has served as a physical and intellectual hub for all the disciplines that cover ancient studies, Anderson says. The museum, which has been closed to visitors for almost three years while updates were being made, offers hands-on exploration of the more than 15,000 objects in its collection, which leans heavily toward Greek, Roman, Egyptian, ancient American, and Eastern Mediterranean pieces. It receives requests for research access and exhibition loans from around the world.

Today, Anderson—along with Kate Gallagher, associate director and curator for collections; Meg Swaney, assistant curator of exhibitions and teaching; and Danute Pérez Radziunas, materials and collections manager—build on that momentum, crafting a space for students and faculty to make intimate connections with the distant past, and allowing them the freedom to follow that experience into new directions of thought.

Changing how we think about the ancient world

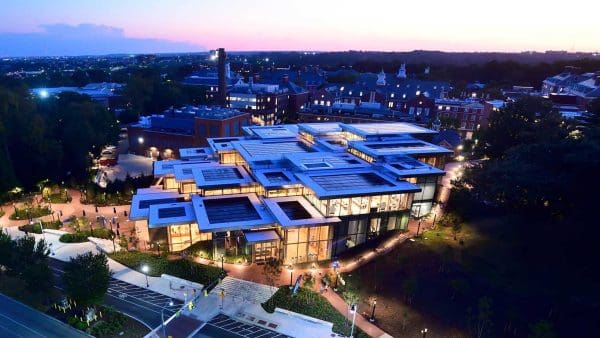

Smack in the heart of Gilman Hall, the museum is impossible to miss. And the central location means that a visit there is not a field trip, but the simple act of walking through a door. Inside, hundreds of undergraduate and graduate students each year have the unusual opportunity to touch objects they’re researching and experience them in three dimensions. The experience often generates new realizations for students.

“When you’re with an object, there are things like the distribution of weight, or the texture, or the idiosyncrasies of its character that you notice, and then noticing that, you start asking new questions about its context, about its involvement in ancient moments of human experience, and eventually, you also reflect on how sitting there with it in 2025 is also part of its biography,” Anderson says. “It opens the door for a whole new way of thinking about the ancient world, but also of thinking about our role in the framing and structuring of what we know about the ancient world.”

The museum plays a particular role at a university like Hopkins, Anderson says, with its wide interest in human health and bodily welfare. From the jewelry that adorned ancient bodies to the surgical instruments whose modern counterparts save lives in the hospital every day, the objects remind us that we’re not so different from those who lived in ancient eras—just separated by time. Examining the physical legacy of the problems our forebears grappled with and the solutions they designed helps us reflect on our own questions, actions, and priorities.

Many ways to interact

Students studying in the museum may encounter a range of experiences. Some might come with a class for a one-time visit that Swaney ’22 (PhD, Near Eastern Studies) contextualizes to highlight and complement other aspects of the course. Others might take a course that meets in the museum for every session, becoming intimate with every divot in an object’s surface and every twist in its history.

“Whether you go on to be an engineer or an archaeologist, having that moment where you think about ancient human experience in a different way is moving,” Anderson says.

Part of what makes interacting with the museum so exciting, Anderson adds, is the way it presents puzzles to solve. Students in her First-Year Seminar recently worked with sherds from the Chalcolithic period in Cyprus, which was very early in the history of pottery (“sherd,” a subset of “shard,” precisely refers to a pottery fragment with sharp edges; the term is favored by archaeologists). Like other ancient objects, the sherds act as lenses on a moment in the past, but it is the viewer’s job to deduce what secrets can be learned from it.

“You move from this little piece of something, and what you have to do is figure out not just what it can tell us, but how to ask it new things. That’s part of the peculiar puzzle work of archaeology,” Anderson says.

The museum’s reopening celebration will be held Monday, October 13, at 5 p.m. at the museum, 150 Gilman Hall.

Must-see objects in the museum

It’s almost impossible to select just a few items from the collection, but Anderson points to the ones below that may hold particular interest for new visitors.

- The Roman surgical kit. With so many pre-med students as well as students, faculty, and staff involved with the medical sciences university-wide, the exhibit provides an important way for viewers to connect ancient and current practices, as well as to consider ancient and current conceptions of the human body.

- The exhibit on jewelry and adornment. Gorgeous and flashy, many of these pieces are made of gold. Their level of detail invites close examination, Anderson says, and the fact that people wore them against their flesh encourages a different kind of consideration of bodies than the surgical kit. “What does it mean that the properties of that material thing were actually taken to be powerful, so it’s not just a matter of aesthetics?,” Anderson asks. Don’t miss the little golden amulet that protects its wearer from the evil eye.

- The mummy masks. In Roman Egypt, funerary masks were created as likenesses of the person whose mummified body they rested atop, serving as a connection between this world and the realm of the afterlife. “Again, this connection between a body then and bodies now makes them more vital, and that experience more present,” Anderson says.

- Bert and Ernie. Yes, really. (Well, close enough.) Cypriot plank figurines from the Middle Bronze Age, two of whom bear a striking resemblance to the familiar Muppets, are often considered mother or Venus figures. The markings and incisions on their bodies invite us to think about the long-ago decisions that were made about what to represent and how to represent it. The figures help us notice that we always view bodies through a particular cultural lens, sparking questions about society and ourselves.