Caroline Lillian Schopp is an assistant professor in the Department of the History of Art. She researches modern and contemporary art and critical theory, with a focus on performance and body art, textile arts, and public sculpture.

What makes a work of art significant?

“One of the exciting things about practicing art history is that you’re providing a vocabulary to establish something like significance, because there are so many different lenses through which the significance of a work of art can be seen.

There’s constant tension in the history of art between works that are lent value through an institutional gaze, and those that accrue value by troubling that gaze; and one could look at the history of art as something that traces those movements.

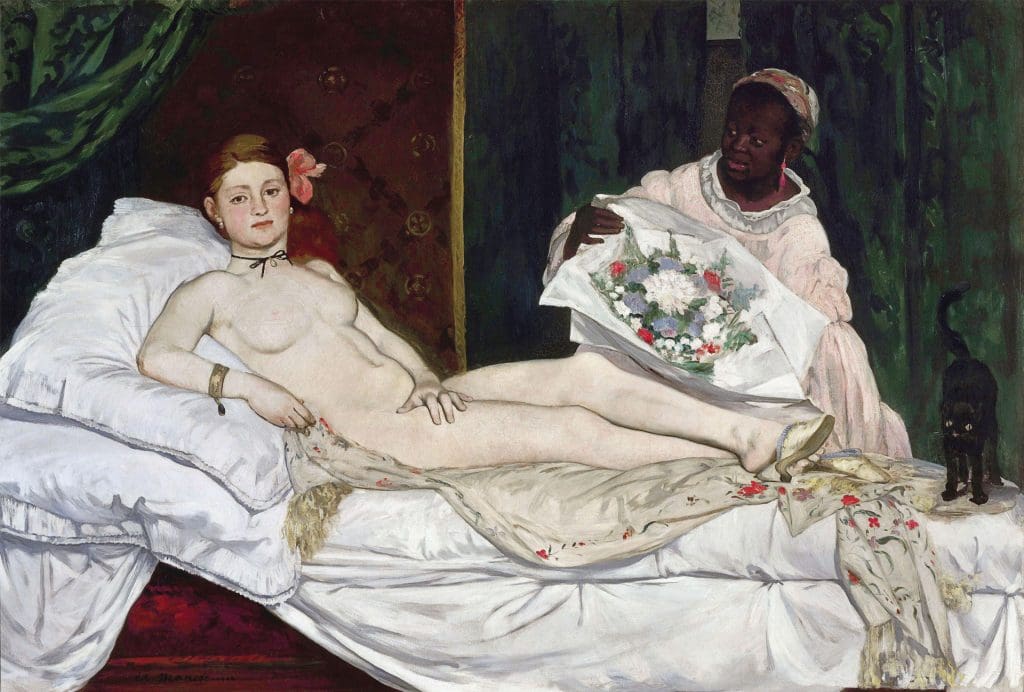

One way I like to think about the significance of a work of art is through the lens of its reception and citation, and a work that I often teach is Édouard Manet’s painting ‘Olympia,’ which caused a huge scandal when it was exhibited to the Parisian public: it depicts two women (and a cat!) in a bedroom interior and raised big questions about representation, social status, consumption, and gender.

Confronting our beliefs

What a work of art can do is confront us with something about ourselves or the world that we live in that suddenly doesn’t seem as simple or familiar as we thought. That feeling of urgent curiosity or uncertainty, or even, as in Manet’s times, of upset and outrage—a good work of art should provoke precisely that, because it then allows us to recalibrate our expectations of what the world makes available to us as given.

I like to say to my students: if you’re saying to yourself about a work of art, this is really weird, or I don’t get it—good. That’s worth dwelling on and then trying to come up with a precise vocabulary to capture that response. In turn, the writer of art history might find themselves using a word, syntax, or affective modality that they hadn’t used before.

Much like ‘Olympia’ in all of its fraughtness—one could continue to say that it’s a bad painting, but even today, it continues to be valuable to say why. That’s a sign of significance as well: a work of art that culture grapples with again and again.”