Last month, about 150 philosophers, scientists, and other thinkers gathered at a Baltimore hotel to...

Last month, about 150 philosophers, scientists, and other thinkers gathered at a Baltimore hotel to...

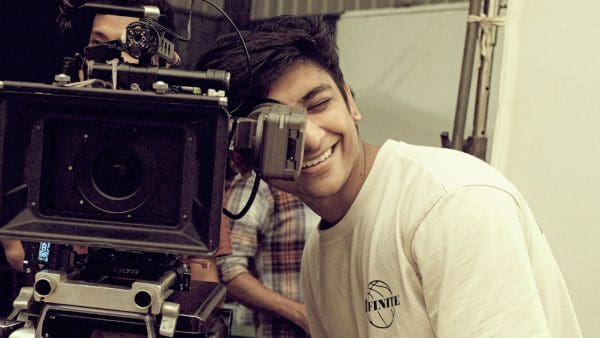

Ragheeb Moazzem found surprising inspiration for a documentary in an archival box. The work ties...

Doctoral student Ezra Sukay uses the James Webb Space Telescope to make cosmic connections.

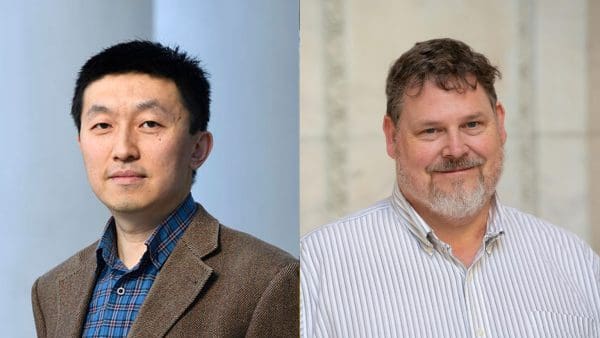

The Krieger School welcomes Yuan He and David DeMille.

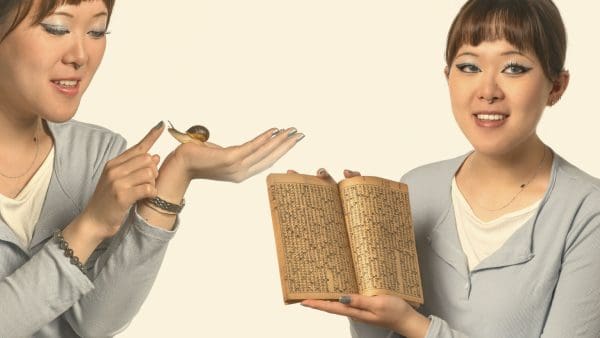

Recent graduate Marie Wei works in both molecular and cellular biology and classics.

Dean Christopher S. Celenza highlights how all types of research at the Krieger School help...

Supporting the San Francisco Gardens of Golden Gate Park.

Film "We Are Guardians" focuses on indigenous communities' fight to save the Amazon.

New research clusters will drive interdisciplinary studies at the Data Science and AI Institute.

Jessica Croteau shows how embracing deterioration could build a sustainable world.

Jocelyne DiRuggiero and her students found a new area of study via isolated cyanobacteria.

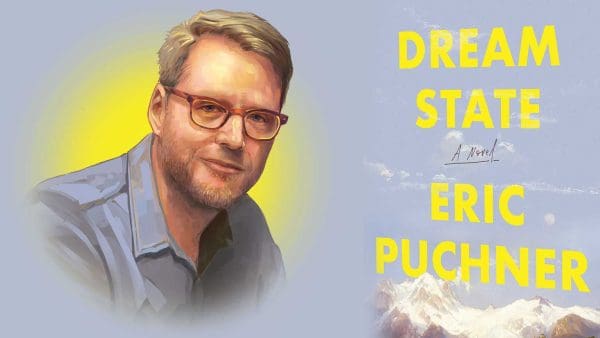

His new novel, "Dream State," was chosen for Oprah's Book Club.