Elin Hilderbrand ’91, has published more than 30 novels.

Elin Hilderbrand ’91, has published more than 30 novels.

Dana Ferraris PhD ’99 contributed to an FDA-approved cancer drug, and runs a cafe.

Rafson is the producing artistic director of one of Off-Broadway’s oldest theater companies.

Angelique Sina MA ’14 co-founded the nonprofit Friends of Puerto Rico.

Associate Research Professor Margaret is examining the landscape of accents in Baltimore.

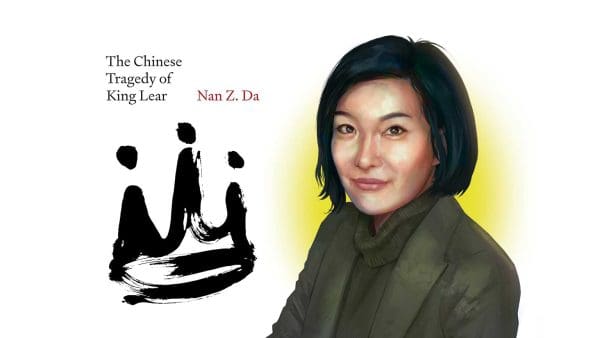

Associate Professor Nan Z. Da's newest book compares Shakespeare's King Lear with modern Chinese history.

Assistant Professor Caroline Lillian Schopp on what makes a work of art significant.

History Assistant Professor Diego Javier Luis is also a photographer.

Lunn is an associate judge in the District Court of Maryland.

JHU students volunteer with Run Baltimore, which offers free kids' running training.

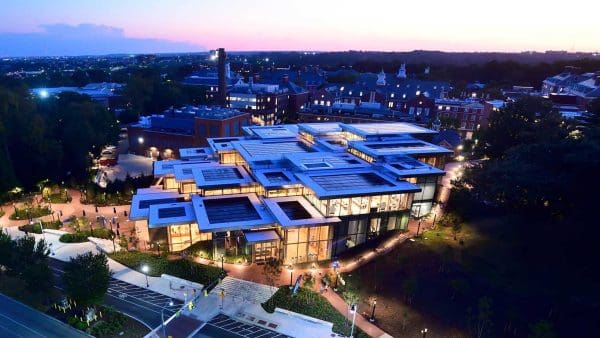

The Bloomberg Student Center has four floors of social and collaborative space.

The Alexander Grass Humanities Institute and Deep Vellum have started a partnership to create new...