Jocelyne DiRuggiero and her students found a new area of study via isolated cyanobacteria.

Jocelyne DiRuggiero and her students found a new area of study via isolated cyanobacteria.

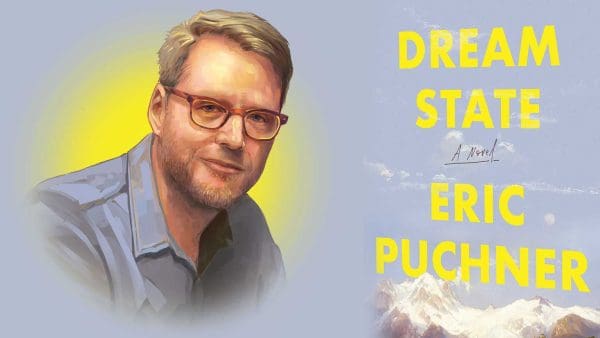

His new novel, "Dream State," was chosen for Oprah's Book Club.

Students visited Honduras this year as part of an Experiential Research Lab.

The Ralph S. O'Connor Center for Recreation and Well-Being is a central student resource.

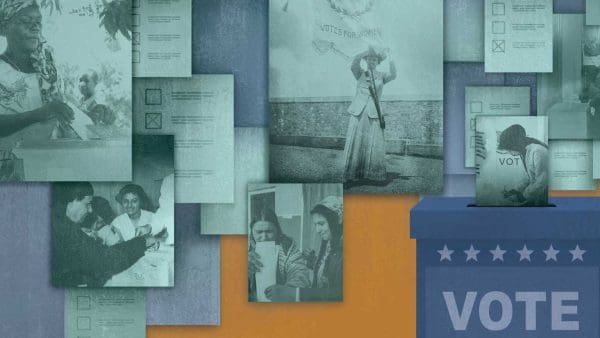

Dawn Teele's research looks at how women voted early on.

Highlighting PhD graduate Jason Mientkiewicz's fellowship at the Baltimore Museum of Art.

Research Professor Harris Feinsod in the Department of English focuses on "blue humanities."

His work at Loyola and Georgetown archives found diverse feelings about changes in the 1960s.

Alum and state delegate is an advocate for clean energy.

Why we yawn and whether yawning in public is actually rude.

Alum and Deputy Director for Astronomy and Physics at NASA.

Callen is a trauma therapist who also works and volunteers in fire and emergency services.