Janice Chen, Psychological and Brain Sciences; Research Interests: Real-world memory, cognitive neuroscience, temporal structure in...

All Articles

The Other America—Waiting to Be Heard

Fall 2016A new book, co-written by Johns Hopkins sociologists Stefanie DeLuca and Kathryn Edin, challenges the...

Curriculum Vitae: Daniel Weiss

Spring 2016Daniel Weiss, President of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

They’ve Got It in the Bag

Spring 2016The President’s Day of Service inspires hundreds of Johns Hopkins students, faculty, and staff to...

Major Infatuation: Biophysics

Spring 2016Students tell us why they love their major, in three sentences or less.

On the Financial Frontlines

Spring 2016Marc Hochstein ’94 is editor-in-chief of "American Banker."

Navigating the History of the Navy

Spring 2016Kristina Giannotta ’03 (PhD) is branch head of histories for the Histories and Archives Division...

Casting an Independent Shadow

Spring 2016Sunday “Sunny” Boling ’99 is a Hollywood casting director.

Tell Me About (Spring 2016)

Spring 2016Three faculty members, one question.

More Faculty Books

Spring 2016New publications from Krieger School faculty.

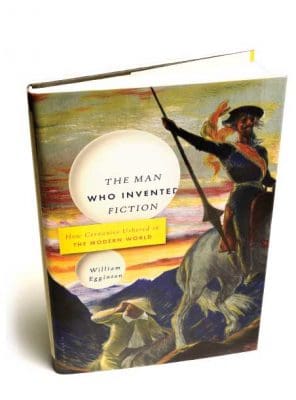

Cervantes: No One-Hit Wonder

Spring 2016William Egginton’s new book on Cervantes arrives in bookstores just in time for the 400th...

The Art of the Book

Spring 2016Book Arts Baltimore is an informal partnership among local institutions whose goal is to celebrate...