Professor Emily Riehl is a long distance runner as well as a mathematician.

Professor Emily Riehl is a long distance runner as well as a mathematician.

A collaborative evening of original compositions inspired by James Webb Space Telescope images.

Students in an intersession course investigated local bacteria and learned to run their own research...

Hilary Gallito ’25 is studying the words of three remarkable Revolutionary-era women who wrote about...

Stephanie Boddie '86 was inspired by her own family and history to study the interplay...

Fourth-year political science PhD student Kory Gaines is analyzing the federal government’s role in civil...

What is the role of the arts at a major research institution like Johns Hopkins?...

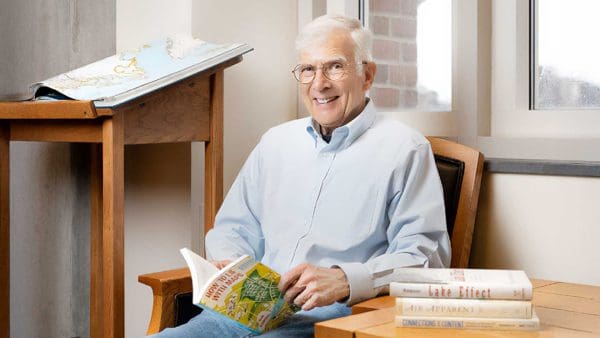

Highlighting Mark Monmonier '64, Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Geography and the Environment at Syracuse University.

See photos from orientation 2024, when JHU welcomed 1,288 members of the Class of 2028.

Assistant professor Brian Camley talks about his horses Felix and Zukini.

Robert J. Barbera ’74 BA, ’78 PhD, lecturer in the Department of Economics and director...

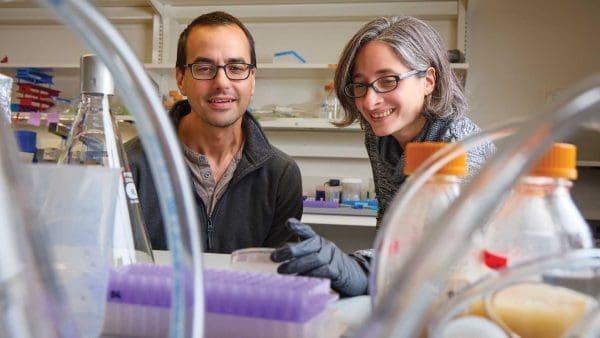

New associate professors Gira Bhabha and Damian Ekiert bring their lab, studying the structural biology...