Rafee Al-Mansur and Mohamed Hamouda are producing a documentary film about African-American and immigrant Muslim...

Rafee Al-Mansur and Mohamed Hamouda are producing a documentary film about African-American and immigrant Muslim...

How do socioeconomic conditions affect life expectancy? Do people in countries with nationalized medicine live...

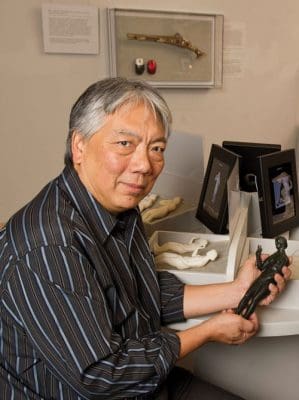

While writing his thesis on Daniel Coit Gilman, Kevin Chun '12 uncovered little-known facts about...

Social Climbers and Charlatans in American Literature is a popular course in the English department.

A faculty roundtable discussion on the economic crisis in Europe…why it started, who it might...

What answer would you give to this Jeopardy-style clue: “it can be as small as...

What answer would you give to this Jeopardy-style clue: “it can be as small as...

In March 2011, Nolan DiFrancesco, a Hopkins junior who was studying at the American University...

It seems that “Lucy” was not the only hominin on the block in northern Africa...

For most of us, the name Galileo Galilei evokes a vision of a nearly infallible...

Worth a Surf: krieger.jhu.edu/film-media Film and Media Studies is an undergraduate program incorporating courses in film history,...

Pick up a pen, a cup, a book—no big deal; we don’t give it a...