A new university-wide initiative aims to change the way science is introduced to undergraduates. With...

A new university-wide initiative aims to change the way science is introduced to undergraduates. With...

“One time throughout the world, one date throughout the world.” —Richard Conn Henry, professor in...

Michael Beard, the aging wunderkind physicist, was worried. “He liked to think he was an...

The summer before I began my job as dean, I was frantically trying to finish...

It takes a steady hand and lots of expertise to preserve an old and damaged...

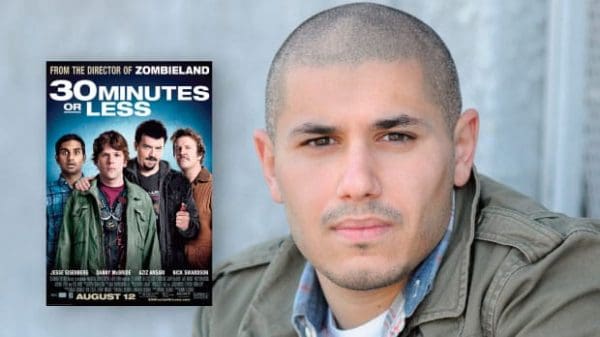

In November 2010, Variety listed Michael Diliberti ’04 as one of “Ten Screenwriters to Watch.”...

“I want you to think about how to get rid of wishy-washy words,” Writing Seminars...

Adam Kline (l) and Fred Finn are dedicated to Washington state residents. They were two...

Chieh Huang ’03 (right) could have been a lawyer, and Chris Cheung ’03 could have...

At no time in recent history has the Federal Reserve garnered quite so much attention,...

Illustration: Robert Neubecker When Melissa Libertus was in high school, she loved math—and was so...

Location, location, location—the popular adage implies a property’s geographical site is the most important consideration...