The banner hanging over the entrance to Levering Hall in the fall of 1968 read, “Welcome Class of 1972.” Growing up in the ’50s and ’60s, I had never seen a date that began with “7.” It seemed impossibly far into the future.

The year 1968 is considered one of the most divisive and important in our nation’s history—the subject of books and articles and documentaries, especially this year, looking back a half century. But the 500 boys/young men (Hopkins went co-ed in 1970) milling in front of Levering that September day had a different perspective. In April of that momentous year, after the Tet Offensive, around the time Martin Luther King Jr. was killed in Memphis, we had all received a letter telling us we had been admitted to Johns Hopkins University.

Most of us had walked across high school stages and gotten our diplomas and switched our tassels and posed for pictures with proud parents a few days before Robert Kennedy was shot in Los Angeles. Several weeks later we had watched the televised turmoil of the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, with police beating protesters in Grant Park as shouting matches erupted inside, then packed our trunks and suitcases, our portable typewriters and clock radios, and traveled to the Alumni Memorial Residence, where each hall had one pay phone and girls had to be out of the rooms by 11 p.m. Though we had student deferments in hand, the possibility of being drafted was always in the background.

This was when freshman orientation was only a couple of days of introducing ourselves to roommates and meeting with advisors, capped off by a welcome assembly in Shriver Hall, where we were addressed by University President Lincoln Gordon and Baltimore Mayor Thomas D’Alesandro III.

The city D’Alesandro led loomed beyond the Homewood campus like the great unknown that was once imagined over the edges of the flat Earth. During that summer, I had sat around at home in Atlanta with friends who were headed to various colleges up and down the East Coast as we tried to figure out why we knew Baltimore even existed. All we could come up with was the Colts, the Orioles, and Fort McHenry.

So, I was curious. I boarded a bus for the city tour offered as part of orientation by the Chaplain’s Office. Atlanta had been the shining city on the Dixie hill of the ’60s, the showcase of the New South with its gleaming, showy office buildings and hotels and burgeoning population, unmarred by snarling dogs and fire hoses let loose on civil rights demonstrators.

The view of Baltimore out of that bus window was anything but gleaming and showy. It was bleak, depressing. I was glad to get back to the elm trees and green grass of Homewood.

Encountering Chester Wickwire

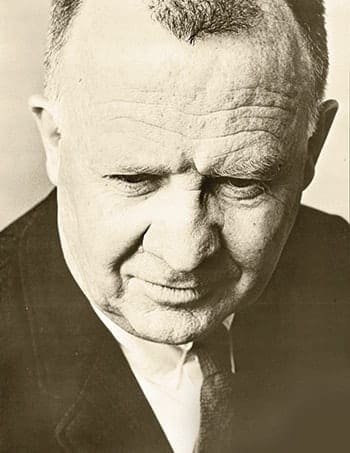

The chaplain whose office sponsored that tour was Chester Wickwire, a smiling, genial man with a crew cut and glasses and a metal cane due to a bout with polio. He was 55 in 1968. As I would come to learn, he was one of the few people on campus actively working to connect the university and the city.

Chester Wickwire from the 1968 Hullabaloo yearbook. [JHU Archives]

“We all knew and loved Chester,” Senator Barbara Mikulski said recently. Now 82, she left her seat in the Senate last year after five terms. Those followed 10 years in the House and six years on the Baltimore City Council. Before that, she was a Catholic social worker turned community activist in East Baltimore.

“You could not be a Baltimore activist and not know Chester,” says Mikulski, who is now Homewood Professor of Public Policy at the Krieger School. “I don’t want to exaggerate my role. I was just a foot soldier, walking up Calvert Street behind people like Chester, who was one of the leaders of the faith-based civil rights movement here.”

Wickwire had brought all sorts of people to Hopkins since he arrived in 1953—from Hugh Hefner to Cesar Chavez to the gay civil rights leader Bayard Rustin, which got a Ku Klux Klan cross burned on campus. He was especially partial to jazz and folk musicians. A young Joan Baez once spent a week in Levering Hall working on an album, playing gigs in the city. In 1959, he had integrated the Fifth Regiment Armory with a concert by Dave Brubeck and Maynard Ferguson. The next year, Duke Ellington appeared at Shriver Hall, and then he, Wickwire, and some students went to the Blue Jay Café on St. Paul Street for a bite to eat. They were refused admission because of Ellington’s race. A furor erupted. A fire destroyed the café soon after. The cause was never determined.

The centerpiece of Wickwire’s work to connect the campus and the city was his tutoring program, started in 1958, that sent Hopkins students into some of Baltimore’s poorest neighborhoods to work with youngsters. That program still exists today as the Johns Hopkins Tutorial Project.

Wickwire had made his way from a religiously fundamentalist home in rural Colorado to Yale Divinity School, and at Hopkins offered theology courses that interested me. But during orientation, I had a brief talk with a top professor in the philosophy department—my tentative major—who discouraged me from taking anything from Wickwire. So, I never did.

That conversation revealed the uneasy relationship between the university and Wickwire. For decades, he was not technically a Johns Hopkins employee. At that time, his salary was paid by the YMCA, which had built Levering and ran its programs. Hopkins academicians were only too happy to turn over the functions of a student union to this outside entity. But some of them could become disturbed when Wickwire brought controversy to their intellectual turf or, even worse, threatened to invade it. Though he had a doctorate from Yale, he had not jumped through the academic hoops strewn along the tenure track so, in the view of some, his courses must not be worthy.

Watching Baltimore Burn

The big blow that 1968 delivered to the city came after King’s assassination when black Baltimore erupted in riots, one of a dozen cities with a violent response to that devastating death. Though many now see those riots as a critical turning point for the city—the moment white flight accelerated to levels that essentially ended one phase of Baltimore history—at the time they were just another blip on the crowded radar screen of 1968’s news events.

“I think the attitude of a lot of people was, ‘What took so long?’” notes Matthew Crenson, professor emeritus of political science. A Baltimore native who graduated from Hopkins in 1963 and joined the faculty in 1969, Crenson viewed the riots from Washington—which had also erupted—where he was working at the Brookings Institution.

“By that time, you had already had riots in New York, Los Angeles, Detroit, and many other cities before King was killed,” he says. In fact, as Crenson points out in his 2017 book Baltimore: A Political History, just a few weeks before King’s killing, Reader’s Digest had run an article titled “How Baltimore Fends off Riots.”

“It credited these satellite police stations that tamped things down at the neighborhood level,” he says. “It almost worked.”

My first trip to Baltimore from Atlanta was just a few weeks after those riots, to check out the northernmost school that had accepted me. I didn’t give the riots a second thought; if you ruled out cities that had seen such violence you would eliminate most of the country’s urban areas. What I mainly remember: Neil Grauer ’69 giving me a campus tour; later, walking by the baseball field dorkily overdressed in a powder blue sports coat when a pitcher launched a ball right at me, which was stopped by the chain link fence inches from my head; the person next to me explaining the rules as I stood in the rain watching my first lacrosse game, with Joe Cowan ’69 leading a 15-7 win over Army.

When I got to Hopkins in the fall, upperclassmen told me of standing on the roof of Maryland Hall and watching Baltimore burn.

John Guess Jr. was a freshman that April, one of a handful of African-American faces on a campus that was beginning to grow more diverse. “I left campus and went downtown,” he remembered. “I saw this little kid standing there and, behind him, these tanks rolling through the streets. That’s something I will never forget.”

Guess said Wickwire had encouraged him to get involved in the city and connected him with students at Morgan State University which led to his becoming student coordinator of Baltimore’s Congress of Racial Equality.

“It was getting to know people like that had led me to head downtown,” Guess says. “I wasn’t near the actual riots, but I did see those tanks. Then I had to head back because of the curfew.”

Once back on the campus that would elect him student body president two years later, Guess found apprehension; “It was like everyone was at a coastal resort and a hurricane was coming. People were wondering where it was going to hit, whether it was going to reach their hotel.”

Baltimore was not a foreign land to Ted Rohrlich. Though he came to Hopkins from Dallas—he and Guess were freshman roommates—Rohrlich had lived in Baltimore for four years, through his sophomore year in high school. He also walked down Charles Street during the riots, but the police stopped him around 25th Street.

“I remember seeing smoke in the distance and feeling completely disconnected from what was going on,” he says.

As a sophomore, Bruce Drake was living off campus when the riots broke out. “I was in an apartment at Calvert and 29th. We climbed up to the roof of the building and the whole southern horizon was glowing with fire.”

Drake was editor of The Johns Hopkins News-Letter (the student newspaper) and says his memories are mostly confined to its Gatehouse office. But looking back at issues from those months, he saw that many stories were about the city and the aftermath of the riots.

One involved Maryland Governor Spiro Agnew, a Republican who had been the choice of moderates and liberals when elected two years earlier. A few days after the riots ended, Agnew called a meeting of more than 125 of Baltimore’s African-American leaders, people who had spent most of the previous days on the streets, urging calm. Agnew dressed them down for losing control of their community, for giving in to the black militants. Wickwire was one of a number of civil rights leaders who signed a letter denouncing Agnew’s remarks.

“It was supposed to be a full-page ad in the city’s newspapers, but The Baltimore Sun refused to run it,” Drake said. “So, we wrote about that. And we ran it in the News-Letter.”

But mainly memories are of a campus that distanced itself from the city during the riots and their aftermath. Rohrlich contrasted the reaction a year later, when police came into the dorms and made three drug arrests. Students poured out, surrounded police cars, and were tear-gassed and Maced. A march on President Gordon’s house followed.

“The attitude was, ‘How dare you mix the city with the campus? We’re untouchable. We can smoke dope if we want to. The laws don’t apply here,’” Rohrlich says. “It underscored the feeling that Hopkins was supposed to be a special place removed from the city, really an ivory tower.”

Bill Leslie, the Hopkins historian of science now working on a history of the university, said it was different on the medical campus because the riots came so close. “You see a lot of reaction there, various programs to try to connect to the community,” he says. “But not much at Homewood.”

“There’s a great story that Hopkins should tell about 1968,” Mikulski says. “A lot of medical institutions left the city, but Hopkins, along with Mercy Hospital and the University of Maryland, stayed. They could have left. That’s not to say their presence has been without controversy, but they didn’t leave and that’s been very important to the city.”

50 Years Later

A month after the riots, 1968 left another significant mark on Baltimore. On May 17, nine Catholic activists—including brother priests Philip and Daniel Berrigan—protested the Vietnam War by taking draft records from a Selective Service office in Catonsville and burning them in the parking lot. The media had been alerted, and the event attracted nationwide coverage.

A few weeks into my first semester, the trial of what had become known as the Catonsville Nine began downtown. There was a march from Wyman Park to the federal courthouse. From the perspective of Atlanta, anti-war demonstrations had been like the World Series—something that happened in other cities far away. But now here was one on my doorstep. I joined the march—it was on October 7, my 18th birthday—completing a personal political journey through 1968, from a Goldwater family, to a Rockefeller Republican, to walking in Martin Luther King Jr.’s funeral procession wearing a McCarthy button, to supporting the Catonsville Nine.

Rohrlich remembered that demonstration for a different reason. “We must have had 40 people come in from out of town for it staying in our two-bedroom apartment. They were lying all over the place. And our landlord decided to pay us a visit that day,” he says. “We had to find another apartment.”

That November, I voted for the first time as Georgia and Kentucky were the two states that granted 18-year-olds that right then. Per instructions, I unfolded the cumbersome absentee ballot in the presence of the registrar in the basement of Shriver Hall, making my mark for Hubert Humphrey. George Wallace took Georgia’s electoral votes.

People celebrating their 50th high school reunions in 1968 had graduated in 1918 and headed off to college—or to World War I. The events of that cataclysmic year certainly played out for the rest of their lives. The same is true of the year we came to Johns Hopkins. Many of the cultural and political schisms that surfaced in 1968 continue to dominate our national conversation. The foreign policy questions raised by Vietnam have yet to be answered. The loss of King and Kennedy is still felt. In Baltimore, you can certainly draw a line between the 1968 riots and the uprising following the death of Freddie Gray in 2015.

There were also seeds planted that year that grew in unexpected ways. Spiro Agnew’s tough post-riot talk attracted the attention of Richard Nixon, who picked him as his vice president. In 1973, Agnew resigned that office, pleading nolo contendere to corruption charges in the same federal courthouse we had marched to five years before.

Tommy D’Alesandro, son of a former mayor and congressman, decided not to seek a second term in 1971 in part because of the toll the riots took on him. But his sister Nancy, who had moved to California, continued the family’s political legacy, getting elected to Congress under her married name, Pelosi, and becoming the first female Speaker of the House.

William Donald Schaefer was Baltimore’s next mayor. He made his name in large part—ironically—because of a seed nurtured by Barbara Mikulski. She was one of the prime organizers of community-based opposition to a phalanx of highways backed by Schaefer that were to crisscross Baltimore, cutting a huge swath out of black West Baltimore and the white ethnic neighborhoods of her East Baltimore, including Fell’s Point, while turning the rundown Inner Harbor into a major intersection. Federal Hill was to be leveled as a geographical impediment.

If that last gasp of Robert Moses-style urban planning had come to be—and it almost did—there would be no Harborplace, no downtown living and entertaining in Fell’s Point and Federal Hill and so many other Baltimore neighborhoods, no renaissance that made Baltimore in the ’80s what Atlanta was in the ’60s. The post-riot bleakness I saw out of the bus window in 1968 turned out to be fertile ground. Mikulski saw it then. Eventually I did, too. It’s why I’m still here 50 years later.

As for Wickwire, he never let up in his dedication to justice. Once elected head of the city’s otherwise all black Interdenominational Ministerial Alliance, he was so trusted in Baltimore’s African-American community that in 1970, when some local Black Panthers were charged with serious crimes—and feared violence from the police—they arranged to surrender to him. Retiring from Johns Hopkins in 1984, Wickwire kept active until his death in 2008 at the age of 94. Wickwire kept fighting, whether the issue was apartheid in South Africa, death squads in Guatemala, or pay raises for Hopkins service workers. And the tutoring program is still going strong, though after the 1968 riots, the city students started coming to campus for their sessions.

When 1972 finally arrived, Johns Hopkins was on its third president since our freshman year. The school had admitted women undergraduates. And we were about to graduate.

Wickwire addressed our undergraduate commencement. He read a poem he wrote called “Meditations on a Journey” that included these lines:

1968-1972

Chaotic, broken trip

years of violence

fallen King

tormented city

You were routed out of bed

in the drug bust

Moontrips/battlefields

Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos

lived when students died

at Kent and Jackson State

Trying to

sell peace at the Pentagon

audition America at Washington’s Monument

face-off against the University over

Recruiting, ROTC, APL, governance

Did not stop

numbers coming up

Who didn’t want to

detour around

a headstone at Arlington?

Some of you went

into the city

to Woodstock

Altamont

Now you sing new songs…

Michael Hill ’72, a social and behavioral sciences major, spent four years on the Johns Hopkins Board of Trustees after his graduation. He was a reporter and editor for the The Baltimore Evening Sun and The Baltimore Sun for 35 years. He recently retired after 10 years as a writer with the humanitarian agency Catholic Relief Services. He lives in Baltimore and New York.

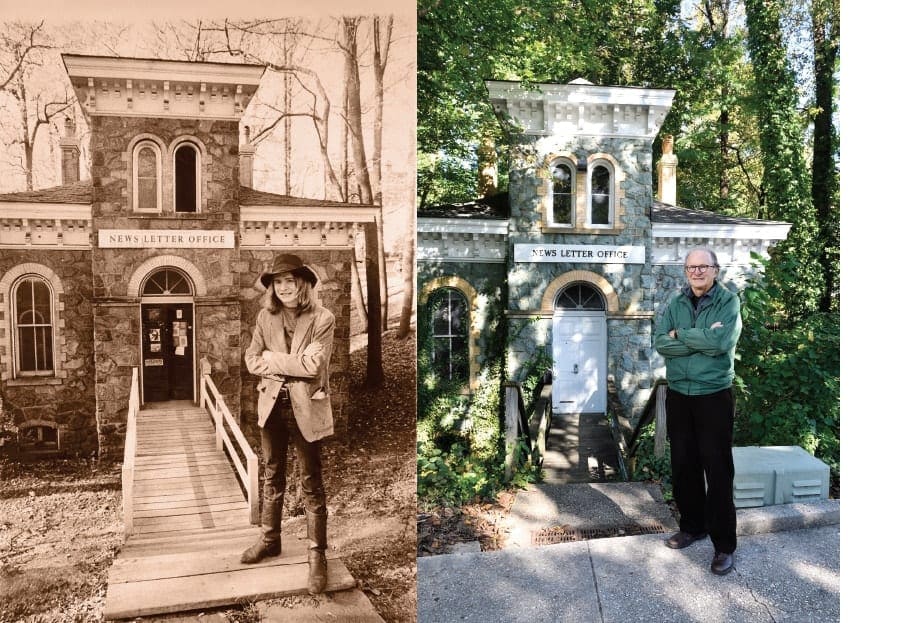

Then and now: Michael Hill in front of the JHU Newsletter office in 1972 (left) and 2018. He was a writer for the paper while at Hopkins.

[photos by Richard Childress and Will Kirk, respectively]