Four stories underground in Johns Hopkins’ Eisenhower Library, Earle Havens and Walter Stephens make their way to “The Cage,” an enclosed, secured area that houses part of the Sheridan Libraries’ Special Collections.

After entering, they proceed to the far wall, where Havens activates an electronic button, and Red Sea-like, opposing stacks of books part to reveal more than 2,000 titles known as the Bibliotheca Fictiva (BF)—a collection of literary and historical fakes, phonies, forgeries, and frauds, plus the scholarly accounts that debunk them.

Literary forgery is a laboratory for looking at discourse in general. There are ways for discovering how texts fall apart.”

Walter Stephens

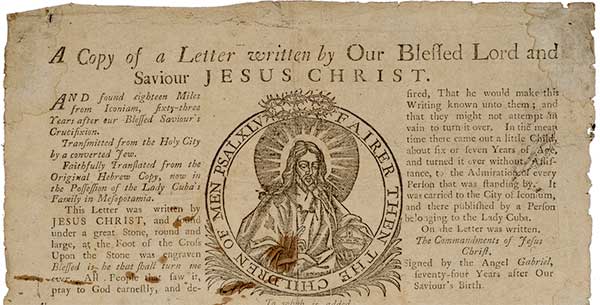

The two men start plucking books off the shelves, taking turns explaining in detail the significance of each. Here’s Havens, the university’s Nancy H. Hall Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts, riffing on the Letter of Lentulus—an infamous medieval forgery, attributed to the Roman official Publius Lentulus, that gives a flowery eyewitness physical description of Jesus (as well as a characterization of his countenance) that has resulted in billions of depictions of the son of God as a proto-hippie.

Why Fake It?

Literary forgers were motivated by a number of reasons such as advancing political aspirations, rewriting history in their country’s favor, advancing untrue religious ideas, or achieving personal gain.

See more of the Bibliotheca Fictiva collection.

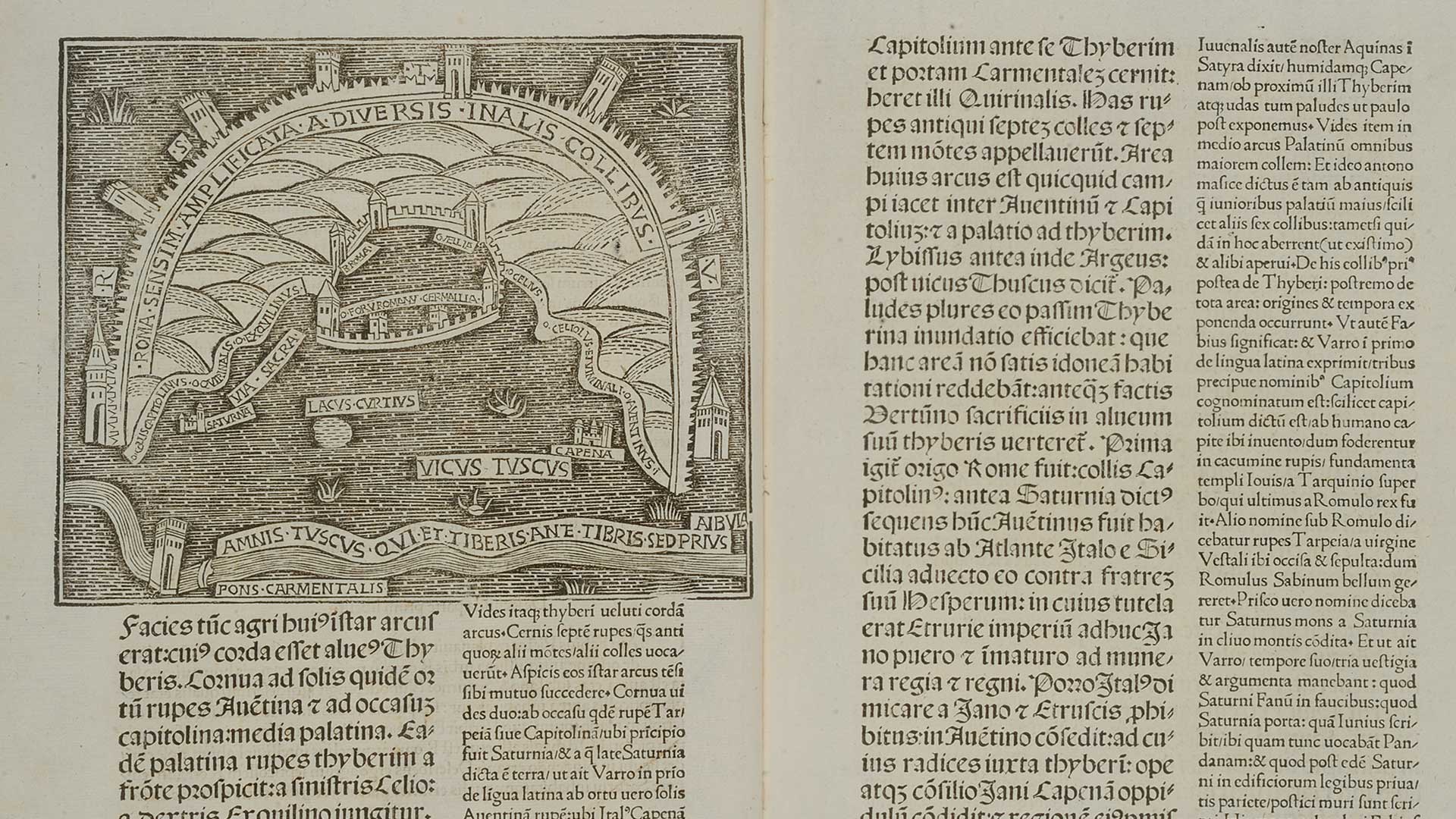

And here’s Stephens, the Charles S. Singleton Professor of Italian Studies, rapping on master forger Annius of Viterbo’s Commentaries on the Works of Various Authors Who Spoke of Antiquity—the meticulously written late 15th-century document that, in short, persuasively rewrote history from the biblical flood that made Noah’s reputation to the mid-8th- through early-9th-century reign of Charlemagne. (“Annius” was actually the wily Giovanni Nanni, considered the most famous forger through the 1650s; his work influenced hundreds of historians and other forgers.)

Both Havens and Stephens exude an unbridled enthusiasm when discussing the intricacies of the Bibliotheca Fictiva (formally, the Arthur & Janet Freeman Collection of Literary & Historical Forgery), much the same way that inside-baseball devotees wax rhapsodic when holding forth on the minutiae of the sport. And they have tapped the collection as a teaching tool, twice conducting a graduate seminar, Literature and Truth: Forgery and Theory From the Renaissance to the Present (in fall 2012 and this past spring).

For Havens and Stephens, the importance of the course lies in the way that it encourages both critical and creative thinking. “It involves rhetoric: How is this text supposed to convince you?” Stephens explains. “It involves history: How does this text fit with what we already know about other texts that are believed to be authoritatively genuine? And it also involves psychology: How the forger tells you what he thinks you want to hear—and how he verifies what you already believe.”

At the same time, Havens point out, teaching forgeries helps students “realize that it is really, really legitimate, even laudable, to have a creative relationship with history. We want our students to be creative thinkers. And, indeed, some of the more inspired creative thinkers of the history of the world actually turn out to be forgers.

“Forgery is a very difficult thing to do well, especially when your audience is the most learned people in the world—people who can read the most ancient languages that you purport to read, as you purport to create new knowledge about the deepest, darkest, remotest antiquity,” says Havens.

Deftly encapsulating that line of thinking, Stephens adds, “[is] the best possible course in detective work.”

More Relevant Than Ever

Havens recalls how, in 2011, he first broached the subject of acquiring the Bibliotheca Fictiva to Winston Tabb, Dean of Sheridan Libraries, Archives, and Museums. The pair’s main argument, according to Havens: “We have never needed a collection on the history of forgery like we do right now in the facile world of digital information.”

These books are obscure, rare things that become springboards for all other kinds of ideas about how you can reconstitute literature and history, and carry that conversation across centuries.”

Earle Havens

Eight years later, in the current media environment of disinformation, alternative facts, and fake news, that need has grown exponentially. “This kind of education is particularly crucial now,” Stephens emphasizes. “Literary forgery is a laboratory for looking at discourse in general. There are ways for discovering how texts fall apart.”

Havens concurs, asserting that the Bibliotheca Fictiva has become essential for students in the wake of a tsunami of fake news; they can examine how it is manufactured, how it is constructed, and apply that to past literary and historical forgeries. “These books are obscure, rare things that become springboards for all other kinds of ideas about how you can reconstitute literature and history, and carry that conversation across centuries.”

It helps them to address “the larger questions that they have about authenticity, about authority, about believability, about what constitutes great literature and great ideas, what does not, and what lies hidden in between.”

Hopkins’ 2011 acquisition of the BF catalyzed the first Literature and Truth (L&T) seminar, which attracted eight graduate students from across a spectrum of disciplines, primarily romance languages and classics. The Sheridan Libraries purchased the trove, originally 1,700 individual titles, from London-based bookseller, collector, and scholar Arthur Freeman, who, along with his wife and co-collector, Janet, carefully assembled the literary forgeries over nearly 50 years, building it into the foremost of its kind. Since the 2011 acquisition, it has grown by approximately 300 titles.

Its contents date from the 12th century (a vellum manuscript allegedly written in the reign of England’s King Henry II) to the mid-20th century (including LoBagola: An African Savage’s Own Story, the exotic 1930 “autobiography” fabricated by Baltimorean Joseph Howard Lee), with the bulk nestled between the mid-15th century to the end of the 18th century, a period during which such publishing chicanery proliferated.

Freeman also christened it the Bibliotheca Fictiva. “In the rarefied world of rare books, so to speak, there is this notion of naming collections,” says Havens. “And it’s not uncommon to Latinize them. You could call your collection the Library of Forgery, but it doesn’t have a ring of authority, which is, of course, the double entendre of that whole concept because this collection is absolutely without authority.”

How to Know a Fake When You See One

Havens and Stephens conduct the L&T seminar tag-team style, which allows the two scholars to talk to each other, comparing and contrasting opinions and interpretations, occasionally even disagreeing. Think: the kind of informed repartee that film critics Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert brought to their long-running shows Sneak Previews and At the Movies, with Stephens in the role of the reserved Siskel and Havens as the demonstrative Ebert.

Each seminar student chooses a document from the BF—or closely related to it—and analyzes it as a text, ultimately “writing a term paper explaining a forgery in historical and/or literary critical/theoretical terms,” says Stephens, and looking to see what’s wrong. “What’s wrong may be rhetorically wrong, it may be historically wrong, or, in some other broader sense, it might be psychologically wrong,” he says.

At times, these forgeries can be so convincing that you second- guess yourself as you are reading. Is this really a forgery or not?”

Janet Gomez

For her inquiry, Janet Gomez ’16 PhD, who studied with Stephens and participated in the first L&T, settled on the influence of forgery after the death of the 16th-century Italian poet Torquato Tasso. “Because little was known about Tasso’s personal life,” she says, “forgers, especially in the 19th century, were obsessed with filling in the gaps and romanticized not only his mental illness but supposed love affair with Eleonora D’Este, one of the princesses of the court of Este where he was a court poet.”

Gomez, who today is director of International Programs and Marketing at Johns Hopkins, says the L&T seminar made her a more inquisitive scholar: “At times, these forgeries can be so convincing that you second-guess yourself as you are reading. Is this really a forgery or not? Like a skilled con artist, a ‘good’ forger—that is, a convincing one—builds on truth or the zeitgeist of the time to cleverly create their fiction.”

Havens and Stephens present students with an array of texts to examine: historical texts and literary ones, along with others that pertain to science and the Bible.

Key to the experience is students’ exposure to the texts as material objects, Havens notes. Marginalia, marks of provenance, evidence from the binding—“all might tell you something about the potential audience, the wealth or lack thereof of the owner, and all of those kinds of things.”

This process is abetted with scholarly texts from the collection that unmask the forgeries. Havens characterizes such books as the “demolition experts—the wrecking balls.”

According to Stephens, it takes several weeks for the students to get the hang of deconstructing the forged texts. “But once the course gets going, it is a group effort,” he says. “You’ve got an historian over here who notices something about this document, and over here you’ve got a literature student who notices something else and a philosopher [who picks up on yet a third element].” The result? “A reading of the document that is potentially richer than any one person can do.”

Last year’s edition of Literature and Truth was pegged to the publication of Literary Forgery in Early Modern Europe, 1450–1800, a collection of 13 essays (edited by Havens and Stephens with assistance from Janet Gomez) which grew out of a 2012 conference that attracted more than a dozen scholars to explore and dissect the Bibliotheca Fictiva. The class brought together 12 students from an even broader field of studies than in 2012, including two from the Department of History of Science and Technology. One of them, Filip Geaman, at work on his PhD, looked at the role of forgeries in the religious culture of the Renaissance period. He is particularly interested in forgery’s links to early studies of the Hebrew language and Jewish history, “especially as these disciplines were communicated by and primarily for a Christian reading public,” he says.

“Beyond the part that these documents played in the social sphere, they had significant ramifications within the fields of linguistics, theology, political philosophy, and even the natural sciences,” Geaman explains. “The history of these disciplines depends on the religious beliefs of the people who developed them, and so the spread of a belief derived from a forgery can have a significant impact on many areas of knowledge.”

Meanwhile, Claire Konieczny, studying for a PhD in French literature (and who audited the course), says she found the seminar extremely useful to her growth as a scholar. “One of the most important takeaways of the class was just how integral forgery, and forged work, is in history,” she says. “This course put into light the fact that any stories that are taken for granted as ‘true’ are very often forgeries—or have forged elements to them.” She was surprised, she says, “that many forged works—often ones that were very clearly forgeries—became the basis of other scholarship that was and still is considered important and foundational.”

“Touch Them, Feel Them, Smell Them”

Next fall, Havens plans to take the fake news/Bibliotheca Fictiva nexus to the undergraduate level by teaching a course for the Krieger School’s Program in Museums and Society. For the moment, he’s vacillating between again calling it Literature and Truth or maybe, he muses, The History of Fake News From the Flood to the Apocalypse, “because, for undergrads, that’ll probably get more familiar lightbulbs going off.”

He’ll use the Bibliotheca Fictiva to probe what he terms “the material culture of forgery,” with, very likely, field trips to the Walters Art Museum to ponder strategies for forging archeological material; to the Baltimore Museum of Art, where “we’ll be thinking about the questions we have about forgery and painting”; and to Hopkins’ Garrett Library, which houses John Work Garrett’s manuscript collection of autographs of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, an area fraught with forgery.

“We will be engaging in that larger thing about what is real and what isn’t and how does it get manifested materially—physically—in the world,” he explains. “It will be a much more broadly conceived course for undergraduates who are being introduced to these questions for the first time, not as current events, but as ancient history.”

While Stephens won’t be involved with the 2020 course, he frequently uses the Bibliotheca Fictiva—and the issues that it raises—when teaching courses in Renaissance French and Italian literature, and neo-Latin literature. He cites the works of Rabelais, the 16th-century French writer, physician, monk, and scholar, as an example. All five of Rabelais’ books are what Stephens has dubbed “fake forgeries,” because “they present you with an authorial persona who is an inept forger, who’s constantly deconstructing everything that he says.”

At a certain point during each class, he marches his students over to The Cage to see the BF, telling them, “This is not just something in the air. These are not texts that are floating free. Here’s a group of books that contain the texts that I’ve been talking about. Touch them, feel them, smell them. Get the dust in your nostrils left behind by centuries of bookworms.”