There should be a word for it: that feeling of pride, well-being, and maybe even power that many of us experience as we leave our polling places on Election Day, shiny “I Voted” stickers announcing our civic engagement—and therefore our belief in democracy—to the world.

What is behind that feeling? What brings so many to the polls for elections large and small, national and local, whether or not we feel passionate about the candidates? At the same time, why do so many—while freely sharing our opinions with bumper stickers, on social media, and with our friends and neighbors—choose not to demonstrate those opinions at the ballot box? In the 2016 election, just under 56 percent of eligible voters weighed in.

Elections, and the process of voting, have been contentious and hard-fought since the beginning of our nation. Many thousands have marched for the right to vote that the Constitution is supposed to guarantee, and far too many have been injured or killed in the process.

Of the many kinds of civic engagement available to us, voting remains perhaps the most basic. But it has never been simple. In this election year, we asked Krieger School faculty experts who have written and taught about the vote, and students who dedicate themselves to getting out the vote on campus, to tell us more about what voting means, and has meant, and could mean, in our country. They shared their thoughts in conversations and writings—compelling morsels that shed a bit of light on the issues from a variety of angles.

Changing Political Parties and Voter Behavior

Daniel Schlozman, Joseph and Bertha Bernstein Associate Professor, Department of Political Science

His 2015 book, When Movements Anchor Parties: Electoral Alignments in American History, explores the role in American party development of alliance between political parties and social movements.

In the 19th century, voting was a radically different experience. There were no secret ballots. The parties had agents at each polling place, and they handed out a physical party ticket with all the candidates for a given party. If voters didn’t like a given candidate, they could scratch off the name, or they could take a ticket from each party and include only certain names, but the parties—not the state—controlled the voting process.

It was a raucous process—and a huge amount of alcohol was involved. Were the tabulations entirely accurate? Probably not. Participation rates among eligible voters in the late 19th century, though, were higher than they would ever be again in American history, because this was an important part of people’s civic sense of self. It was a process that worked very well for able-bodied male citizens, but it was a distinctly male process. And it did not do well by disabled voters, and in places where African Americans had suffrage, they faced a lot of discrimination.

It became much easier and less expensive to have the state distribute ballots, and so the old system went away. And with it, atrophied a whole infrastructure that brought people into politics and made voting really central to their lives.

There are reasons not to be nostalgic for this system. There are reasons, though, to think that if you want to have a world in which more people are voting and in which politics are more central to their lives than the atomized world we have now—and a world in which people’s commitments are not expressed just by watching cable news or posting on the internet but by engaging with their neighbors in a public way—then there are real lessons from the 19th century.

[Photo: Everett Collection Inc./Alamy]

100 Years of Women Voting

Sen. Barbara A. Mikulski (Ret.), Homewood Professor, Department of Political Science, and special advisor to JHU President Ron Daniels

She joined the faculty in January 2017 after completing her fifth six-year term in the U.S. Senate, becoming Maryland’s longest-tenured U.S. senator.

Knowing our history is important. It is how we learn who we are, where we come from, and most importantly, how to be better than we were before. Knowing the history of women’s suffrage in America—the full history, including the good and the exclusionary—matters if we are serious about women’s equality today. And getting the vote mattered because it laid the groundwork for each subsequent fight for women’s rights, but it took time.

Even after women were granted the right to vote, their participation started slowly. At first, women seemed reluctant to vote, but then they started showing up and kept showing up at the ballot box in growing numbers, before eventually running for political office themselves in the 1960s. This change came with the second wave of the women’s movement, which reached its peak in the 1960s and ’70s. That movement gave us household names like the late, great Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm. It was also the movement that helped me launch my own political career in the 1970s. But that movement wouldn’t have been possible without the first wave of the American women’s movement: the battle for women’s suffrage.

And now, we women, and the men who support us, find ourselves fighting again for equality, both in the law books and the family checkbooks. And in doing so, we stand on the shoulders of the countless suffragists who fought for our rights, so we can continue the fight today.

Voter Suppression and the Voting Rights Act of 1965

Martha S. Jones, Society of Black Alumni Presidential Professor, Department of History

Her work examines how black Americans have shaped the story of American democracy. Her latest book, Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality, will be published in fall 2020.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 inaugurated an unparalleled period in our democracy. Individual states could no longer require poll taxes, literacy and understanding tests, and other barriers to the ballot that had long kept many black Americans from the polls. Not only did black Americans enter the body politic in unprecedented numbers in the wake of this legislation, but the Voting Rights Act guaranteed equal access to the polls for all Americans with a promise from Congress and enforcement by federal courts.

That era came to end in 2013 with the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Shelby v. Holder. That case cancelled out the Voting Rights Act’s most effective provision. No longer would federal officials exert oversight over changes to election laws in those states with histories of voter suppression. Shelby opened the door to a new tragic era of voter suppression. Today our voting rights are compromised by ID requirements, curtailed access to polling places, and the purging of voters’ rolls. In this sense, the era of the Voting Rights Act, from 1965 to 2013, was an exceptional one in U.S. history. For a generation, Americans enjoyed unparalleled access to the polls. In the next generation, the challenge will be to win back that foundation of our democracy.

[Photo: Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg via Getty Images]

Voting to Maintain Democracy

Yascha Mounk, senior fellow, the SNF Agora Institute and associate professor of the practice of international affairs, Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies

Mounk is a political scientist known for his work on the rise of populism and the crisis of liberal democracy. He is a frequent contributor to The New Yorker, The New York Times, and The Atlantic.

When I was in graduate school, I learned a few basic propositions about democracy. In affluent countries with long democratic traditions, democracy was safe because most citizens were committed to their political system. As a result, they would value their democratic institutions, reject autocratic alternatives to it out of hand, and refrain from voting for political parties or candidates that attacked democratic norms and institutions.

Over the past years, these basic propositions have all, to varying extents, proved open to doubt. Across the world’s democracies, a majority of citizens is now dissatisfied with their political institutions. A growing share of voters is becoming more open to autocratic alternatives to democracy. And most importantly of all, authoritarian populists who openly challenge long-standing democratic norms have won big victories on virtually every continent.

It would be easy to locate the fault for this development with voters. If only they voted for more sensible parties—or didn’t have such high expectations of their institutions—things would be better. But the truth is that voters are more critical of their political systems in part because those systems have become less adept at delivering on their priorities.

For those who value democracy, it is important to reject populist candidates. But the real solution to the current crisis lies not [just] in citizens voting differently; it lies in politicians and institutions living up to the responsibility they have long neglected.

Finding Common Ground

Hahrie Han, inaugural director, SNF Agora Institute and professor, Department of Political Science

She specializes in the study of civic and political participation, collective action, and organizing, with a focus on the role civic associations play in mobilizing participation in politics and building power for social and political change.

Democracy depends on citizens working together for a common good. Research, however, shows that humans are not inherently equipped to bridge difference and find common ground. From the ancient Athenian agora to the Founding Fathers of the United States, the architects of democracy have always recognized this fact. As James Madison famously wrote in The Federalist Papers, “But what is government itself, but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary.” Nonetheless, democracy has held at its center an audacious—yet fragile—promise.

Given what we know about human nature, the challenge is to create settings that make it more likely that people will engage in pro-democratic behavior. Research on civil society offers two key principles to guide us: First, recognize the social dimensions of democratic life as the foundation for productive dialogue. Second, design (online and offline) civic spaces to encourage people to develop cross-cutting, deliberative capacities.

We can start by creating spaces that bring together people who are different from one another. Once in those spaces, we know that things like asking people to share stories, instead of engaging in wonky policy debates, make it more likely they will develop the connections needed to form an empathic bridge. We need to pay careful attention to inherent power imbalances and structure spaces to attenuate those imbalances. Finally, attention to the broader political context of those settings can shape the extent to which people commit to sustaining these new relationships.

Building these agora-like spaces is not a magic bullet, but the beginning of changing what is possible.

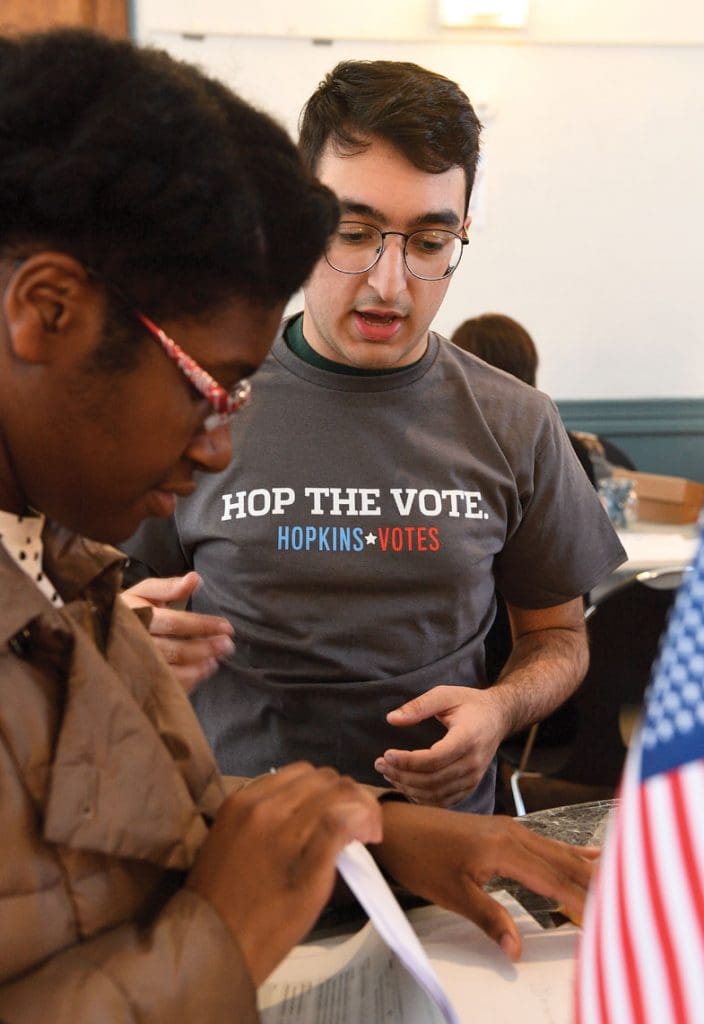

Hopkins Students Sign Up to Vote

Hopkins Votes is a civic engagement, nonpartisan campus organization that aims to equip all students who are eligible to vote with resources and knowledge.

Currently, 48 students volunteer with Hopkins Votes, which launched in 2018 following low voter turnout among Hopkins students in the 2014 midterm elections. As a result of the group’s efforts, more than 5,000 more Hopkins undergraduate and graduate students voted in 2018 than in 2014, increasing voter turnout among students by more than 30 percentage points, from 14.4 percent to 44.8 percent, according to the National Study of Learning, Voting, and Engagement. In recognition of this jump—among the largest at any college or university in the country—Hopkins Votes received two awards from the All In Campus Democracy Challenge: a Best in Class award for most improved voting rate; and a Gold Seal for achieving a voting rate between 40 and 49 percent.

Student volunteers with Hopkins Votes use a variety of strategies to boost voter participation, including providing stamps and assistance with absentee ballots; shuttles to early voting locations throughout Baltimore; voter registration and information booths; election day Lyft codes for free rides to local polling locations; a festive Absentee Ballot Party for students to request or submit their ballots; and an event for National Voter Registration Day.

Ryan Ebrahimy ’22, political science major

Ryan has been involved with Hopkins Votes since September 2019. He works with academic departments and Homewood Student Affairs to develop campuswide voter outreach strategies.

What inspires me to vote and to excite other people to vote comes down to my identity and family history. I’m Persian, the son of immigrants who came here from Iran. The U.S. is a great place for opportunity and holds a lot of promise for immigrants—but there’s something unique to be said about the Iranian American identity as it pertains to American politics.

My community is often the subject of divisive rhetoric, and the same can be said for other vulnerable communities. But more often than not, we’re not at the table making political decisions; our voice isn’t heard. I don’t often see the Iranian American identity present in American politics, but we’re often part of the rhetoric, so I felt there was a disconnect. How can one group be the subject of so much political controversy, but not play a role in steering that conversation and adding our perspective to it?

So that inspired me to become politically active, and with that comes civic engagement and, inherently, voting. And I see the value of making sure that everyone has a seat at the table, where they’re not just subjected to the opinions of others, but they’re also able to express their own.

It might be easy to succumb to the feeling that one’s individual vote does not matter, but it’s important to consider that voting is as much an act of civic engagement as it is one of principle. There is an inherent responsibility to be involved in our government and to make sure that you’re in these political discussions. If one person makes the effort to vote, then that could inspire someone else to come out and vote.

Ally Hardebeck ’20, public health and sociology double major with a minor in social policy

Aly joined Hopkins Votes in September 2019. She reaches out to campus student organizations and student leaders.

My interest in becoming more civically engaged started when I participated in a Pre-Orientation trip with Habitat for Humanity, which opened me up to learning about historic housing discrimination and social inequality, particularly in Baltimore. I grew up in Baltimore County, so I was here when the 2015 unrest [following the death of Freddie Gray in police custody] happened, and that was kind of telling because I think people reacted to the unrest in a way that didn’t account for the decades of systemic oppression that were the context for people participating in it. So I was interested in trying to become more politically active, and to educate myself more in the policy sphere.

As I’ve gone through my undergrad years, I’ve become more interested in thinking about how to advocate for racial equity—particularly in Baltimore, but everywhere. I’ve come to realize that civic engagement and voter engagement is a huge part of that, and you need to be working on multiple fronts to effectively create change.

Baltimore is historically a place of extremes and segregation and division, and students can feel intimidated or unsure how to engage with that. Hopkins Votes offers a very attainable, bite-size step you can take, just to be registered, just to inform yourself even a little bit.

It’s been great to see how students are responding. The enthusiasm and willingness to collaborate have been really promising. It’s important to make the goals we’ve set, to register a certain percent of Hopkins undergrads. But making civic engagement more fundamental to the culture of everything we do, so there’s some aspect of it in every sector of student life—that impact could be even more long lasting.