A Teachable Moment … Online

Former Wall Street economist Robert Barbera’s Macroeconomics Strategies course typically covers topics like the anticipation of economic turning points, business cycle basics, and interactions between monetary policy, the financial market, and the real economy.

When the pandemic hit and Johns Hopkins announced it was moving to online classes after spring break, Barbera shifted not only his method of delivery but also the focus of the content. Now, using the same forecasting tools as before but applying them to an unprecedented situation, he says the 22 juniors and seniors in his class are grappling with vastly amplified economic signals as the virus plays out, including the impact of physical distancing on “Main Street” (the gross domestic product); the “cacophony of bankruptcies” that could result from the way Wall Street tends to magnify adverse shocks; and what happens to the economy when trillions of dollars are injected.

Barbera notes that as students try their hands at predicting key economic barometers like GDP, oil prices, the consumer price index, and unemployment rates, their forecasts tend to cluster around tame levels; GDP predictions usually range from about 1.8% to about 2.6%. Now, they fall in the “otherworldly” territory of negative 16% to negative 25%.

The pandemic has turned into nonsense some of the accepted principles surrounding the way markets tend to balance themselves out, he says, when considering what could happen when 20 million people lose their jobs at once, for example.

“As a teaching moment, it’s important for me to get students to understand that the model we usually traffic in is very useful a fair amount of the time, but you also need to be an economist who can step outside of that framework,” says Barbera, lecturer in the Department of Economics and director of the Krieger School’s Center for Financial Economics.

The pandemic provides a teaching moment more generally, he adds: “The elemental lesson the world is confronting now is that, on occasion, circumstances arrive that the private sector cannot deal with. I, for one, hope that the world will climb out of this crisis with a greater willingness to embrace collective action. It may be wishful thinking, but perhaps we will become much more aggressive on climate change, having suffered through the downside of waiting too long to heed the judgments of experts.”

Remote Metrics

On average, in the first weeks of distance learning, the Krieger School had approximately:

- 700 Zoom meetings per day (typically 500-600 per month)

- 6,200 Zoom participants

- 260,000 Zoom minutes

- 120 new Panopto videos created

—Compiled by Mike Vanschoorisse, IT Manager, Krieger School

Color-coded Classroom

What usually happens after spring break in Jimmy Joe Roche’s Introduction to Digital Production course is that students watch one another’s films together and then critique them. “That dynamic has really changed,” says Roche, a lecturer in Film and Media Studies. “The live aspect of being able to tailor the experience to react to something in real time is more complex now.” Instead, students must watch the films on their own, take notes, and then have a class discussion online.

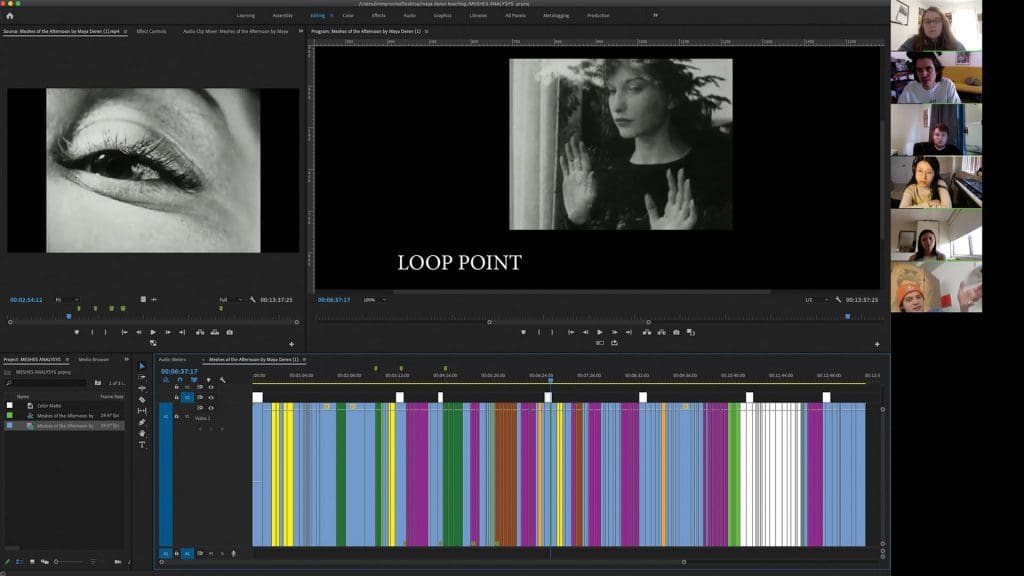

But Roche has developed one innovation that’s working so well he plans to keep using it. To help inspire the students for their own projects, he typically shows Meshes of the Afternoon, a short experimental film by Maya Deren and Alexander Hammid. Instead of trying to show the film over Zoom, he pulled it into the video editing software Premier, and color-coded each cut based on concepts. For example, he turned narrative-based sections with strong continuity red. Sections with alterations in the use of perspective became green. Beautiful examples of cinematography were yellow.

“I could then jump through and discuss topics throughout the film, and move through it nonlinearly,” he says. “The thing I was able to get at here, in some ways more successfully than I’ve done in the past, was that some of the preconceived notions of what the film is might be—on more in-depth analysis—incorrect. I could have done that before, but it took the change in teaching styles and the totally screen-based moment for the idea to come to me and for me to execute it.”

“Some of the most brilliant and exciting artists I know often find ways to turn challenges into strengths or to conceptually wrap them into the work itself, so I’m hoping—no, I know—that we will see some of that not only in film, but in all kinds of work,” Roche adds.

Virtual Fieldwork

Understanding Baltimore: Introduction to Field Methods in Anthropology typically starts with readings and discussion of ethnographic method, followed by brief ethnographic exercises around campus, followed by open-ended assignments in Baltimore’s neighborhoods. Students might attend services at a house of worship to observe the ways community is formed there, or spend time in a market to see how its small-scale society is organized. The idea is to learn how informal institutions function within their neighborhoods through repeated, personal observation and engagement.

It was at just that in-depth point in the schedule that the university moved to distance learning. As instructors Niloofar Haeri and Thomas Özden-Schilling discussed how to translate such on-the-ground experiences into virtual ones, they were inspired by Özden-Schilling’s wife, School of Medicine postdoctoral fellow Canay Özden-Schilling, who was helping to organize a network of volunteers for grocery runs, medical supplies, and telephone check-ins with their Bolton Hill neighbors—the sorts of activities that were creating a new kind of community around the world.

The different kinds of processes people were going through to reorganize their daily lives and call something a community were absolutely something we could study as ethnographers.

—Thomas Özden-Schilling,

assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology.

By shifting the focus from existing neighborhood institutions to emergent ones, the instructors were able to guide students in observing what was safely available to them. They contacted students to learn about their individual situations, and helped them develop projects tailored to their own interests, says Haeri, professor in the Department of Anthropology, who designed the course with Jane Guyer, George Armstrong Kelly Professor Emerita in Anthropology.

One student is watching online classes offered by a local mosque to learn how a sense of community is cultivated when people can no longer gather physically. Another is learning from her physician mother’s colleagues about the flow of information in a hospital setting. Another, observing dialogue on social media, wants to find out why some people fully embrace stay-at-home and other physical distancing measures while others think they go too far.

“It’s lucky, because we’ve been able to come up with a project that each student can do—without compromising their safety—and at the same time still learn interview skills, how to look for sources of information, and how to use images and videos that are available,” Haeri says.

A Conference Reimagined

Last fall, Natalie Strobach launched plans for something that had never been done before: a conference showcasing humanities research by 400 undergraduates from around the country. Strobach, assistant dean of undergraduate research for the Krieger School and director of the Office of Undergraduate Research, Scholarly and Creative Activity, quickly found an eager audience. The inaugural Richard Macksey National Undergraduate Humanities Research Symposium was set for April 3-4, and hundreds of students registered and made their travel plans.

When COVID-19 hit, Strobach wavered briefly, then pivoted. The conference would go on—virtually. She asked participants to make their presentations online, where they will appear in mid-May and remain available for six to 12 months. After a long search, she found a vendor able to host not just papers and posters, but all of the original formats—films and poetry readings and PowerPoint talks—that the students had worked so hard to prepare. And she asked the students to contribute to an online journal of conference proceedings, and is hiring student editors for a remote editorial board to curate them.

When Strobach emailed the participants explaining the situation and offering refunds, only 15 percent requested them. The rest—about 400 students from 320 colleges in 45 states, Puerto Rico, the United Kingdom, Canada, and India—pivoted with her.

Students step up to the plate

When students find themselves needing a little extra help understanding a course’s material, they have an assortment of programs available from the Office of Academic Support. These range from help with study skills and time management; to drop-in tutoring as needed; to longer-term, more personalized tutoring; to intensive weekly collaborative learning sessions. Besides academic assistance, these programs also offer the kind of social networking that can help students feel supported, connected, and encouraged.

When the move to distance learning was announced, Jessie Martin, assistant dean for academic advising, wasn’t sure how these programs would continue to function—especially the social part. The programs rely heavily on the 400 trained student workers who serve as facilitators and tutors. Under university guidelines, they would be paid for the next month or so whether or not the programs went forward, so she wondered if they would choose to continue.

“The students contacted us saying we have to keep this going,” Martin says. “There is such commitment between students to help one another. We were able to start online academic support the same day as classes started; no delay. We couldn’t do it without the students.”

The student leaders quickly worked to see how they could retain both the academic and social elements of their programs. For example, leaders in the collaborative learning program—called peer-led-team learning, or PILOT—polled the students in their groups to see where they were located around the globe and added sessions to accommodate a variety of time zones, says Ariane Kelly, director of academic support. The Learning Den tutoring program, led by Kaitlin Quigley, has maintained group and personalized tutoring as well as drop-in support through virtual help rooms. In the study skills group, student advisory board leaders added workshops on taking online classes and following virtual schedules, as well as tips for maintaining overall well-being, says Sharleen Argamaso, assistant director of academic support for study consulting. And instead of the usual post-study rituals like going out for pizza together, leaders and peers are staying connected through platforms like Zoom and social media.

Building a Routine

For Kale Hyder ’22, the hardest part of moving to distance learning came in the first week—spring break—when there was no structure yet and lots of uncertainty ahead. But once online classes began, he quickly found a routine, and even some silver linings.

Hyder’s large lecture classes, like Physics I, haven’t changed much. But a small class on travel writing has shifted to make use of the technology Zoom offers, splitting into breakout rooms to edit papers online, for example. Meanwhile, he’s discovered a new efficiency to his days as he’s now able to put to better use the brief blocks of time between classes usually taken up by navigating across campus.

“What’s kept me the most sane is building a routine,” Hyder says from northern Virginia.

Self-care is essential, Hyder says, whether that means taking a walk, driving into town to remind himself of the larger civilization benefitting from stay-at-home measures, or using an old Wii Fit to get his heart rate going. “Just because we’re quarantined doesn’t mean you have to be sedentary,” he says. He also does a lot of writing—“a brain dump to make sense of what’s happening”—and enjoys extra time talking with friends and relatives by phone.

Last fall, Hyder—a neuroscience major—began working in a lab at the School of Medicine, tracking participants’ performance in a motor task. With those activities on hold, he’s turned to data analysis and preparation for a paper he will write with his research advisor.

Student Voices

I think the worst part is trying to keep track of all of my assignments and lectures that I have to attend. My professors each send multiple emails a day, so it can get really clogged up. I’ve been using organizational planning sheets and those have helped me manage my time well. I’m a part of [the Johns Hopkins chapter of Camp Kesem, a national program led by college students that supports children whose parents have cancer], and our summer camp that we’ve been fundraising for all year has just been replaced with an online camp. We don’t really know how that is going to work out because it’s not necessarily something that transfers well, but we know it’s for the best.”

—Riley Difatta ’22, April 2, 2020, Detroit, Michigan

Adapting to online classes has definitely been tough, given it is the middle of the semester. For me at least, I was not supposed to go home for spring break either, so it was very weird being home at first but I have slowly adjusted. For the most part, my professors have adjusted their grading/syllabi and have been more lenient in terms of due dates, which has been nice. … In terms of connecting, I’ve really tried to put an emphasis on FaceTiming my friends or even doing Zoom calls for the ‘Bullpen,’ which is where I do economics research, … just to make it feel like I’m working with other people.”

—Alexandra Johni ’22, April 1, 2020, St. Petersburg, Florida

Staying connected

Several days before Johns Hopkins announced it was moving to online classes for the rest of the semester and students were being asked to return home, junior International Studies major Bonnie Jin began hearing about similar decisions from friends at other institutions, and immediately recognized the straits some students would find themselves in.

Building on a familiarity with the principles of organizing and with the Baltimore community that she had developed through volunteer work, Jin created a spreadsheet where those with resources to offer and those in need of resources could find one another. Located in Google Docs, the document includes such searchable topics as housing, food, healthcare, child/pet care, and emotional/spiritual support. Spreading the word through Hopkins student groups and the Student Government Association, as well as through her community contacts, Jin watched the responses begin pouring in.

“I can pick up groceries and deliver them anywhere within walking distance of campus,” wrote one user. “My family and I are struggling through the virus, three us have been laid off and are not sure when work is going to come through,” wrote another.

The last week of March, Debanik Purkayastha, a senior in the Whiting School of Engineering, contacted Jin. He was a programmer, he said; would she like to pool their skills and turn the spreadsheet into a national website? The two set to work migrating all the information, and the website—something Jin hadn’t even dreamed of a few short weeks earlier—went live the first week of April. It is currently 1,203 volunteers strong, and growing.

The original document’s title, “Baltimore Mutual Aid Spreadsheet,” was very intentional. Mutual aid, Jin notes, is the idea that the world does not actually run on the dog-eat-dog doctrines of social Darwinism, but instead relies heavily on cooperation and reciprocity.

After this crisis is over, there will still be students that are struggling and community members that are struggling, so I really hope we can continue this mutual aid.”

—Bonnie Jin

Answering the call

Boris Steinberg, building manager for the chemistry department, is keeping things rolling by conducting critical lab equipment checks in compliance with university regulations, coordinating a lab renovation project in Remsen Hall, and picking up the mail. But on weekends, he can be found on the Johns Hopkins Health System’s volunteer assembly line—workstations are spaced at least six feet apart—making face shields and personal protection packs for Hopkins health care workers. The volunteers’ original goal was 50,000 kits, but by mid-April, they had reached 100,000.