In the predawn chill, the cadets pounding the track circling Homewood Field are working up a sweat. “I’m trying to ride that wind—makes it easier,” calls senior Jack Dunn as he rounds lap 5. One cadet stops running and hunches over; others rally around with encouraging words. She returns to the track, which is empty by the time she triumphantly finishes—only to discover she miscounted and has one more lap to go. Five cadets who had concluded their runs join her and they complete the last lap together.

“I don’t like to think about how hard it’s going to be,” Dunn says afterward, steam rising from his hair in the cool morning light. “Your body takes over; your mind kind of stops working.”

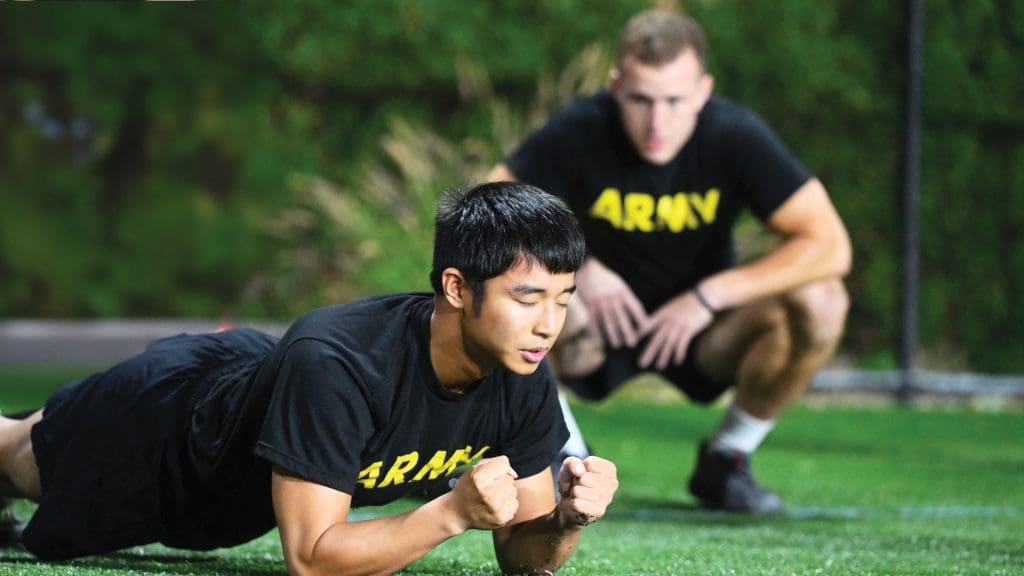

The 2-mile run is the final event in the Johns Hopkins ROTC battalion’s grueling physical training test this morning, which opened with deadlifts, medicine ball throws, pushups, a sprint-drag-carry activity involving kettlebells and a 90-pound sled, and planks (“Think firm thoughts, Dunn. Rocks. Walls,” Capt. Timothy Leung urges the horizontal Dunn). Passing is 60 points out of 100 in each of the six events; achieving the full 600 points for the day is a rarity.

“I just want to say good job to everybody that came out here and put forth good effort today,” Lt. Col. Brandon Thompson tells the cadets afterward, urging them to invest time in physical training on their own every day. “You’re going to need to take care of yourself to take care of your soldiers one of these days—in a few years or a few months, some of you. Good work out here today. Let’s continue to improve.”

Dunn gathers his gear. “Now it’s time to go do school stuff. And we have football practice later,” he remarks.

The core of the corps

The Reserve Officers’ Training Corps as it exists today has been around since 1916, providing full scholarships, monthly stipends, and military training to undergraduates around the country in exchange for a minimum of eight years of service after graduation—at least four years active, with the Reserves or National Guard as options for the remaining four.

The Blue Jay Battalion—whose affiliation is the U.S. Army—also got its start in 1916, and currently includes cadets from University of Maryland Baltimore County, Stevenson University, and the University of Baltimore, in addition to Hopkins. The 52 cadets are regular students with majors and full course loads, and participate in all aspects of college life. They also spend 10–14 hours a week with their battalion, conditioning their bodies and learning to lead. Time management is key, notes Dunn, who occasionally even finds time to noodle on his guitar with a friend.

It’s not for everyone. Mornings are early; physical training is held at 0530 three days a week. Standards are high; the cadre—the battalion’s full-time commissioned and non-commissioned officers—constantly monitors cadets’ academics, physical fitness, and leadership skills. Responsibility is demanding; the entire program is aimed at preparing cadets to lead their own platoons (35–45 soldiers) as second lieutenants right after graduation, so by the time they’re seniors, they’re in charge of trainings and briefings, personnel and supply, and communications.

Students who thrive in Johns Hopkins ROTC are often the same ones drawn to joining sports teams or leading student organizations, Thompson says, though many have different backgrounds and interests. It is similarly heavy on camaraderie, unity, loyalty, and shared purpose.

When things get tough, it’s like the idea of being in a team sport—it’s not communal suffering exactly, but it’s ‘we’re all in this together struggling.’ That’s what builds a team.”

—Jack Dunn ’24

ROTC “Summer Camp”

Last summer was the longest Shivani Kapoor has ever gone without speaking with her family: 12 days. Like most of the battalion’s rising seniors—known as MS-IVs, or Military Science class IV—she spent 35 days at Fort Knox participating in one of ROTC’s biggest milestone events: Cadet Summer Training (CST), fondly known as summer camp.

“It was probably one of the hardest things I’ve ever done,” says Kapoor, a neuroscience major minoring in music. Her CST performance earned her the role of battalion commander for the fall 2024 semester. “It was definitely challenging at times physically, but I think it really tests your mental resolve as well.”

You’re going to need to take care of yourself to take care of your soldiers one of these days.”

—LTC Brandon Thompson

Cadet Summer Training is what a cadet’s first three years of training build up to. It reinforces skills like land navigation; first aid; rifle marksmanship; and chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear training. And it includes a 12-day practice deployment, fully outdoors, requiring them to plan and carry out complex operations against an opposing force. Leadership is a constant theme and necessity as cadets coordinate closely with strangers from around the country.

“If you had asked me three years ago to work with 40 people who I’d never met before and just figure it out, I don’t know that I would have been able to do that. It was really a testament to me for how much I have learned and how much I’ve grown through the program,” Kapoor says.

Finding something in yourself

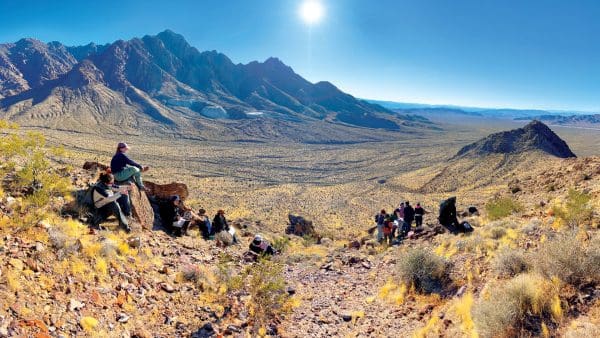

Cadet Summer Training is a time of individual and group challenge and triumph, of chiseling down to your core and finding something unexpected, of exposure to peers of every background and leaders of every style.

“I honestly thought it was awesome. I love being outdoors, and that’s what a big chunk of it is,” says Dunn, an economics major who’s on the Hopkins football and wrestling teams. “When things get tough, it’s like the idea of being in a team sport—it’s not communal suffering exactly, but it’s ‘we’re all in this together struggling.’ That’s what builds a team.”

When the going gets hardest, Kapoor says she focuses on why she signed up to begin with. “Remembering that I’m doing this for a purpose and there is a larger reason for why I’m here keeps me going,” she says.

After three years of observing and trying out leadership styles, Dunn sees himself as a “servant leader,” someone who demonstrates that he’d never ask a soldier to do something he wouldn’t do himself. “It’s the idea of being the first guy on the field, last guy off the field,” he says. The army encourages leaders to get to know not just their soldiers, he adds, but their soldiers’ families, what their lives are like outside of the army, and how they react to different leadership styles.

During summer training, Dunn says he saw so many leadership styles that it was impossible not to learn something from them. “Being able to do all this leadership with others, and bounce ideas off of each other, and being able to collaborate, was awesome,” he says.

He found moments there for another kind of awe, too. During the 12-day stretch outdoors, he looked up one afternoon and watched a gigantic storm rolling in across the Kentucky sky. “I felt like there was something so much bigger than me out there,” he says. “I felt very minute, and it’s a big world. To see it all in motion was absolutely beautiful.”

In the field with Johns Hopkins ROTC

Once each semester, the battalion heads off campus for a weekend training event, usually held at the military training area at Gunpowder Falls State Park just north of Baltimore. This Field Training Exercise (FTX) is a time to apply skills learned in weekly classes and labs, like land navigation and troop leadership, and is part of the build-up toward CST.

The battalion arrived yesterday, dined on MREs (Meals Ready-to-Eat), and slept under the stars, bundled in army-green sleeping bags. Now, MS-IV Gabe Insler is kneeling in the leaves with his team—half of a squad—and a set of laminated, color-coded circles and ovals that serve as models of the “enemy” (other MS-IVs who already completed CST), whom the team is preparing to “attack.”

“Bravo, pick up,” Insler orders. The team follows him into the woods.

After the exercise, the “enemy” will assess the teams on their stealth, among other things, but silence is elusive in the crunchy November leaves. Bearing weapons (unloaded) and packs (35–40 pounds), Insler’s team makes its way through the trees until it reaches the linear danger area; in this case, the road.

On the move with his pack, Insler’s heart beats fast. He has to keep track of where his team is in relation to the enemy, get to the next location without being attacked, and avoid friendly fire. “You’re trying to balance everything you know in your mind and organize it to find your best scheme of maneuver where you want to go,” Insler, a political science major and history minor, says later.

When the squad leader gives the command, the teams slink into attack position atop a tree-studded hillside. Some cadets crouch behind trees, others take cover behind fallen logs. Eventually, the squad leader opens the attack: “Bang bang bang!” she shouts. The others leap forward, and the air fills with cries of “bang bang.” A few minutes later, a ceasefire is in place, and the cadets gather to debrief.

“I think that mission went pretty well,” Insler reflects. “Comparing this mission to our last one, we’re only getting better as the day goes on.”

Learning leadership skills

Insler, who hopes to branch into military intelligence in the reserves—though he won’t get his assignment until he completes CST this summer—says some of his most memorable Johns Hopkins ROTC moments so far have happened at FTX. He often finds himself applying those leadership skills in his other activities, like fencing and his fraternity.

“I’ve become much more of a people-centered person through the ROTC experience,” he says. “I’ve learned a lot more to rely on other people, but then also to be the person that other people can rely on.”

Designing the FTX challenges serves as a milestone for the MS-IVs who will soon receive their commissions. They plan 90 percent of the weekend, Thompson says, with cadre offering resources as needed.

Kapoor, who is spending the day as one of the “enemy,” is gratified to see the results of her cohort’s efforts. “We had a lot of people working very hard to make this happen, and it was a lot of fun to see our planning come to life,” she says.

The cadets don’t know it yet, but cadre has ordered Chick-fil-A to be delivered for dinner, giving them a break from MREs.

The impact of ROTC

In December, most of the MS-IVs got their branches, which means they now know how they will spend the next four years. Dunn got his first choice: infantry active duty. Kapoor also got hers: a delay of her service obligation, allowing her to enroll in medical school; she plans to attend Uniformed Services University in Bethesda, Maryland. Education delays are also available for law school.

The skills honed in ROTC translate smoothly to medicine, says Madeline Donnelly ’20 (Whiting School of Engineering), a former Blue Jay cadet who is now a fourth-year medical student at Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine in Richmond, Virginia. This summer, she will start her service obligation with a residency at Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio, Texas.

“The community I developed through ROTC was one of the best parts of the program,” says Donnelly, who entered college unsure whether she had the social skills to pursue medicine. “Through ROTC, I learned that I did, if I challenged myself to develop those skills. I really like the mentorship opportunities in ROTC, and it parallels medicine with its emphasis on teamwork and a close-knit community in rather stressful circumstances.”

While ROTC roots run deep and are lasting, many student-athlete-musician cadets say it doesn’t fully define them. “I don’t like to pigeonhole myself, because one day I won’t be a football player; one day I won’t be a wrestler. One day I won’t be a soldier,” Dunn says. “Yes, those things form part of my identity and will always impact me. But first and foremost, I’m myself at the end of the day.”