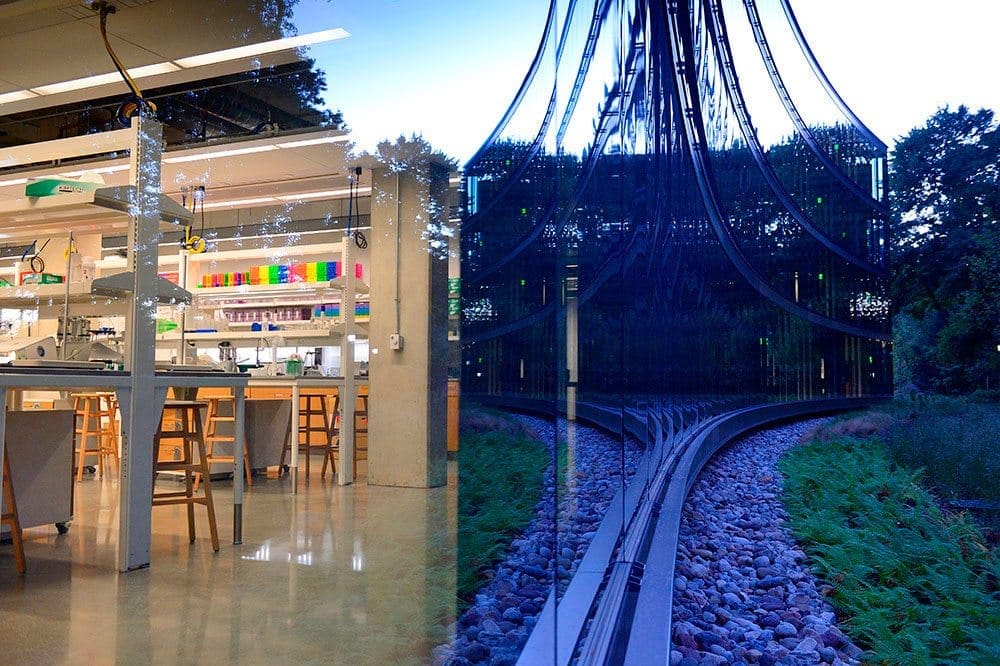

The fall semester marked the opening of the Undergraduate Teaching Laboratories, rising in a graceful sweep of glass, air, and light. Nestled next to the Bufano Sculpture Garden hillside, the labs form the fourth side of the Mudd/Levi/Biology Hall complex. Here is where biology, chemistry, neuroscience, and biophysics will be taught in some inventive new ways.

Teaching Science in new, collaborative ways

When Katherine Newman, dean of the Krieger School, gazes at the Undergraduate Teaching Laboratories’ curving wall of glass, she sees nothing less than intellectual ambitions taking on physical form. “It’s inspirational, graceful—it’s evocative of the creativity we find in the labs,” Newman says. “The building expresses what we value in the next generation. Bold statements of an architectural nature express that durable commitment to science, to discovery.”

The UTL is much more than a building. It’s also a symbol of a commitment to undergraduates and to a groundbreaking kind of education. It’s a catalyst for new ways to approach science, research, and curriculum. It’s a promise to reconnect to the passion for exploration and the joys of discovery—to scientists getting a kick out of science, Newman says.

Right foreground: Professor Beverly Wendland, chair of the Department of Biology, talks with a student in the UTL’s airy atrium.

The UTL is one piece of a constellation that also includes the university’s Gateway Sciences Initiative (a multidimensional program to improve and enrich learning of introductory science courses), the new Bloomberg Distinguished Professor program, and the Krieger School’s mission to train the next generation in life sciences. New hires will use the research space to grow new domains in science. The impetus for the building, and the principle behind its design, was a shift away from teaching science to students and toward creating the conditions for them to figure out how to be scientists.

For something that’s such a step forward—architecturally, educationally, and technologically—the UTL draws deeply upon an intellectual past, one before departments became so specialized, and when universities were places of apprenticeship where scholars converged and students gathered at their figurative feet, says Gregory Ball, vice dean for science and research infrastructure. University departments developed as a structure to organize intellectual thought, Ball says, but they can also create silos that impede creativity.

“What we’re trying to do is change so that people entering the STEM disciplines see it as an odyssey, a life of inquiry,” Ball says. “Hopkins started out on the apprentice model. Instead of being constrained by the department model, the UTL will bring together some of the critical sciences in one place and facilitate teaching in integrated ways. We want to promote teamwork and team building, intellectual activities, cooperation. This building is set up to encourage people to connect with each other, and that will contribute to the overall culture of the campus.”

Beverly Wendland, chair of the Department of Biology, agrees that research needs to be conducted on more interdisciplinary levels. “That’s how we want to train our future scientists,” she says. “Creating a space where those connections can happen, it naturally becomes an idea incubator. The transparency of this building invites curiosity about what others are doing.”

Wendland says the UTL isn’t just about providing new ways of learning for students; it is also a space where teaching and research can become more and more integrated. “For example, we’re incorporating new types of lab exercises that collaborate with the actual research laboratories of faculty members, so students are working side by side with researchers on active projects. It’s taking research to the next level.”

Professor Bertrand Garcia, chair of the Department of Biophysics, works on a computer model with a student.

A scientific playground for students

Biophysics Chair and Professor Bertrand Garcia-Moreno had already started to integrate research and undergraduate education over the past couple of years, offering teaching labs in his own laboratory, based on problems of his own research. He has also tested the idea that in one short summer, an undergraduate can master what is needed to engage in original research. But he sees a rare opportunity to deepen that process in the UTL, which has the potential to turn undergraduates into scientists from Day 1.

Students in Garcia-Moreno’s lab courses—many of whom are taught by research scientist Carolyn Fitch—learn about genes, about the proteins the genes encode for, and what happens when something goes wrong in the gene. And the proteins and data students develop will likely feed back into the Garcia-Moreno research lab for further study, and also become part of a growing database that scientists around the world are using to test ideas about how mutations affect genomes.

“The UTL should become the playground for the students,” Garcia-Moreno says. “We can begin to evolve courses in which students really lead the research, have freedom to move between the project lab, the computer lab, and the biophysics lab. You can imagine this will become the hub of the intellectual life of undergraduates in science.”

Garcia-Moreno says science will always be about the fundamental questions—things like why we are the way we are, and how we got here—but the science majors of 2013 need experience with today’s tools, especially computational approaches. Using computation, students can explore, for example, how a gene evolved, how a protein might have existed in a primitive organ, and how it changed over time. The hypotheses produced with the computational studies can then be tested experimentally in the lab. With its sophisticated computer lab and technology throughout, the UTL anticipates the integration of computation into science learning.

“The future of biology is in the quantitative treatment of data,” he says. “By learning to write code, you’re basically learning a way of asking questions because you’re learning how to think logically and logarithmically, and how to break down problems into tractable parts. If we produce a generation of freshmen and sophomores comfortable with computation and quantitation, then that will effect change in upper-level courses.”

One of the students who took Garcia-Moreno’s course in the old lab space, biophysics major Josh Riback ’13, saw it as a preview of graduate school, of a research environment where questions are “unbound” by prescribed processes and students stand in charge of their own investigations. The UTL opens up this experience as a way of life for science undergrads, says the New Jersey native.

“Because the questions haven’t been answered, you can learn so much more,” Riback says. “You have to think about what the data really mean and be able to explain it because the answers have never been there. When you’re forced to own a question and a hypothesis, your drive for learning the technique and really understanding it beyond preparing for the test is incomparable.”

By breaking down departmental walls, by letting students lead their learning, the UTL will shift the educational focus toward overarching ideas—an approach that may well spill over into Hopkins as a whole. “We may see a revised curriculum that could impact how departments are organized,” says Garcia-Moreno. “A facility like this could have an impact on the traditional structures that are typical of the American research university.”

Professor Linda Gorman and once of her students examine a brain sample in the neuroscience lab.

“Ideas are popping here like crazy”

Neuroscience Professor Linda Gorman has been asking for the new facility for so long she can scarcely believe it’s here. She knew that neuro majors needed to see and touch the brains they study, and they could only do that in a bona fide teaching lab. Gorman plans to contact the Maryland Zoo and the National Aquarium to acquire brain specimens for students to examine in the new lab, and can’t wait to watch them compare the brains of a whole variety of species and witness their differences firsthand.

“When you compare across animals, it really drives home the structure-function relationships. Now that we have the space, there’s so much more we can do,” says Gorman, who is also the neuroscience program’s director of undergraduate studies.

Gorman actually started such a lab in the basement of Dunning Hall and taught there for 10 years, but there was no way around the fact that the space was overcrowded and outdated. In the new space, each station has its own video screen, so students can watch Gorman’s procedures while completing their own, and then share their work with their peers on 55-inch HDTVs mounted on the lab’s walls. A wireless mic lets Gorman talk with the whole class while roaming the lab.

The technology is definitely part of it, but Gorman says there’s also something less measurable that will deeply affect the quality of her students’ scholarship. “Is it going to make them smarter, better students? I think so,” she says. “There’s an intangible thing to it, sort of an excitement that you teach along with the content. They remember it better and longer. It may drive their research later.”

Neuroscience major Melissa Terry ’13, from New Jersey, expects the new lab will help future students find their way as scientists more quickly and enjoyably. “Labs here my first three years were a source of tension; Orgo lab was like going to a dungeon,” she says. The space, light, and appeal of the new lab promote a different frame of mind. “When you’re that much more relaxed, you can actually learn things. Lab should be a time to just go in and explore and learn some science, not be stressful.”

By nature, the field of neuroscience is already highly interdisciplinary, but Gorman is looking forward to expanding on existing collaborations. “There are going to be ideas popping around here like crazy,” she says.

Assistant Professor Tyrel McQueen (second from left) and Senior Lecturer Jane Greco (right) in the new chemistry lab.

An experiment in learning

It used to be that if you came to Hopkins with a very strong background in chemistry, you could go directly into Organic Chem, and otherwise you started in Introductory Chem. But what if you had lots of chemistry course work but little lab experience, or your chemistry background had a narrower focus? Orgo would likely be too challenging, and Intro too boring.

Today, you would take Jane Greco’s Applied Chemical Equilibrium and Reactivity course in the fall, followed by Tyrel McQueen’s inorganic Chemical Structure and Bonding course in the spring—both with integrated labs. “Our courses fill the intermediate gap,” says McQueen, assistant professor of chemistry with a joint appointment in the Department of Physics and Astronomy.

This intermediate option, with labs that coordinate with the lectures, would not be possible without the freedom of space the UTL offers. The 96 roomy hoods and benches stand in sharp contrast to the old chem lab space in Mergenthaler Hall, housing just 70 hoods with poor sight lines and space so cramped students had nowhere to put their lab notebooks.

Not only is the space an improvement, but the configuration—six pods of 16 hoods—allows instructors to differentiate the work students do. For example, through a Gateway Sciences Initiative grant, McQueen will tie his course’s labs to his own materials discovery research. Breaking his students into groups, he’ll have them make a variety of metal-organic framework compounds (MOFCs) and explore their properties, from hydrogen storage to capturing carbon dioxide to separating gases. While not necessarily groundbreaking, it will be meaningful research with no prescribed answers.

Greco and McQueen say students exposed to research so early in their careers, as well as to a range of scientific endeavors, will become more comfortable with—and excited about—real scientific thinking, the kind that expects the unexpected.

“Our result is all a learning experiment. It’s not a right or wrong,” Greco says. “There’s not a bad day in lab; there’s a different outcome that you can seek to understand. With all the additional instruments, we have more ways as faculty members to help students understand those results.”

“The experiment can fail spectacularly,” McQueen agrees. “But it’s never been done before, so failure isn’t that it’s terribly wrong but about ‘what happened?’”

Students will also feel more like “real” scientists because they’ll be around so many other scientists—both neophytes like themselves and veterans. Poster sessions in the airy atrium will expose students to one another’s research. Labs sharing floors will help students explore how other disciplines relate to their own, notice techniques that are similar and different, and ask about the link between a scientist’s goal and how he or she designs an experiment.

“Often missing in undergrad chemistry education is helping students make connections. We’re going from many independent silos of information to a more unified understanding,” McQueen says.

Chemistry major Andrew Griswold ’15 is looking forward to the chemical reactions students will be able to conduct in the new labs. Many reactions are air-sensitive and must be done under nitrogen lines, for example, which weren’t available before. “Now you’ll learn the modern chemistry you’ll be doing research on, and learn the ways people are currently doing it,” says the Massachusetts native, who serves as a teaching assistant for Greco’s course and spent part of his summer moving chemicals into the new building.

Professor Joel Schildbach with a student in the biology lab.

A passion for science

When Allyson Roberts ’16 was preparing to register for her first classes at Johns Hopkins, she was overwhelmed by all the choices. She noticed a class called Phage Hunting, which sounded intriguing, and she signed up. At first, going to the lab every day was daunting; she wasn’t sure what she was doing. Two months later, however, she was still challenged but no longer frustrated.

“I [came] to realize that this is what science truly is: guess and check, make mistakes, and learn how to correct them,” says Roberts. “I’m asking questions, being intrigued by my work, and living for trial and error.”

It is that moment, in all its messiness and uncertainty and maybe even panic, that Joel Schildbach wants every undergraduate to experience. We don’t learn by following timeworn instructions in a lab textbook and getting the same results as the person at the next bench, he notes. We learn by figuring out our own questions, creating a process to search for answers, and recognizing that we’ve gained something even if the answer isn’t what we’d hoped.

“We need to have students take control of their own learning,” Schildbach says. “We’re not an information delivery system; instead, we facilitate the process of them teaching themselves.”

Learning like that can happen anywhere, but Schildbach thinks a lot more of it will happen in a building like the UTL, and so does Roberts, who was one of just a few students selected to attend the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s recent national phage hunting symposium. Powerful as her class was, the symposium, where she saw students just like herself doing “incredible” research, was truly inspirational. Seeing its potential got her so excited about research that she switched her major from neuroscience to biology, and her career aspirations from medicine to research.

Schildbach expects the UTL will give students a good dose of inspiration by helping faculty members rekindle their own enthusiasm for their work, and model it for the next generation.

“Everybody who’s running a research lab and standing in front of a lecture hall—they all got there because they had a certain passion about the work, and why can’t we convey that on a daily basis through the labs that we’re requiring of the students?” he asks. “My participation in the phage lab has really invigorated my teaching simply because I’m faced with ‘why did I get involved in the first place?’ On some level it’s not even teaching; it’s hanging out in the lab space and helping students get the same joy out of science that I do.”

The short list

Here are some of the usual and not-so-usual facts and features of the Undergraduate Teaching Laboratories:

Fast facts

- 106,000 square feet

- 20 teaching wet labs

- Student project lab

- Computer lab

- Instrument core with NMR facility

- 20 bays of research lab benches

- Procedure, tissue culture, autoclave, and cold rooms

- 143 high-efficiency fume hoods

- 560 locked drawers for student storage

- 4,000-square-foot atrium

- Coffee bar

- Cost: $62 million

- Architect: Ballinger of Philadelphia

- Construction: Whiting-Turner of Baltimore

Efficiency features

- All rainwater runoff from the new addition and interior courtyard is routed to rain gardens, which allow the water to soak into the ground instead of draining to the public storm sewer system.

- High-performing exterior envelope including low-emissive windows (they reflect heat while allowing light to pass through)

- Chilled beams (air blows over coils to deliver cooled air)

- Energy wheels that recover heat/moisture from exhaust air and transfer it to the incoming outside (ventilation) air. (The lab constantly exchanges 100 percent of air. But air also has energy, so the big vertical wheels let the air pass, allow airborne debris to escape, and capture the energy for reuse.)

- Occupancy sensors that control both lights and HVAC systems

- Low-flow water fixtures

- High-performing fume hoods

- Energy-efficient lighting

- Daylighting and views to nature in the labs

Chemistry major Felipe talks about the new Undergraduate Teaching Labs (UTL) and what the space means for undergraduate research.