For most of us, the name Galileo Galilei evokes a vision of a nearly infallible “father of modern science”—a man of learned truths, a visionary undeterred by the ritualistic and religious trappings of his time. Most of us do not picture a prolific astrologer who not only made a pretty penny by teaching this now faux-pas subject to his students, but also by erecting elaborate horoscopes for the Italian elite. He was so interested in astrology, as a matter of fact, that he spent a great deal of time preparing horoscopes for himself and his daughters.

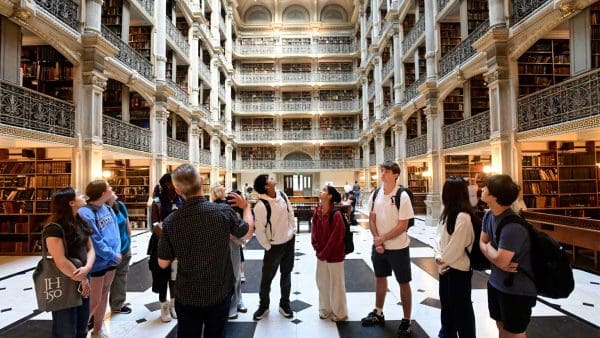

Professor Lawrence Principe (standing) explains the intricacies of the astrolabe, once a popular tool among astronomers and astrologers.

Will Kirk / Homewoodphoto.jhu.edu

We tend to remember Isaac Newton the same way—as a mathematician and scientist of the noblest order; not as a practicing alchemist, or a man with abiding interests in biblical prophecy. The same goes for Robert Boyle, one of the most respected chemists in history, who also spent nearly 40 years attempting to discover the “philosopher’s stone.” (This substance, it was believed, could turn lead into gold.)

These outcast disciplines of science—astrology, magic, and alchemy— are actually as intertwined with our scientific history as astronomy, medicine, and chemistry. “They are crucial parts of the human attempt to understand the world,” says Lawrence Principe, who teaches the graduate seminar titled Wretched Subjects, after the term historian of science George Sarton once used to dismiss such pursuits.

“We don’t want to have a history of science that’s written backwards—that only tells us where our current ideas come from,” says Principe, who is the Drew Professor of the Humanities in the Department of History of Science and Technology and Department of Chemistry (the only dual appointment in science and humanities at Hopkins). “We want a truer depiction of the development of science. The truth is, astrology, alchemy, and magic were widespread practices that contributed to modern science and involved extremely intelligent people.”

And they still involve smart people, such as Principe and the graduate students who make up the Wretched Subjects class roster. The course embodies “the venerable Hopkins tradition,” Principe says, of a high-level graduate seminar focused on a very specific subject, with a small and already expert student body. “The training wheels are off,” he explains. The students represent the future of this academic niche and are expected to use this course as a springboard into careers as active, publishing scholars.

“I think this study is a rich and fruitful exercise,” says Justin Rivest, a second-year graduate student earning his PhD in the history of medicine. “What is history for? Is it just for confirming our own present beliefs? There aren’t many schools with people like Larry who are willing to tackle this subject through a graduate course that tries to understand our past on its own terms, even the parts that seem strange.” Rivest came to the course with a particular interest in the history of astrology, which he’ll be quick to tell you was once a staple of the formal study of Renaissance medicine. “Usually it was the job of the chair of the mathematics department to draw up horoscopes and almanacs for the doctors and medical students. That way, for instance, they would know the most favorable days of the year for bloodletting.”

To construct such horoscopes, medieval and Renaissance academics would use tools like the astrolabe, which Wretched Subjects students studied and used this semester. A cross between a slide rule, inclinometer, and star chart, the pie-sized disk contains an array of moving parts that can give the apt user a variety of heavenly information, from when the sun will set on any given day, to when to expect the appearance of certain stars in the night sky. It was, and still is, an incredible scientific invention. But the astrolabe is of use only to those who understand the Zodiac. No amount of “traditional science” can be gleaned from it without knowing the symbols of the astrological calendar (like Gemini) and the months to which they correspond. At a time when astrology was deemed just as viable as astronomy, the two disciplines shared ideas, as do biology and chemistry today.

“This is the true depiction of science’s dynamic development,” says Principe. “There has been a tendency in the last 200 years to try to separate the history of astrology from astronomy, alchemy from chemistry, magic from natural science. But there really was no clear historical distinction. The same people were practicing both. They were using what they had at their disposal to do the best that they could.”

Spend enough time thinking about this and one might start to wonder: Are we—right now—swearing by the efficacy of some culturally accepted science that our descendants will eventually deem “wretched”? Principe guesses, “probably.”