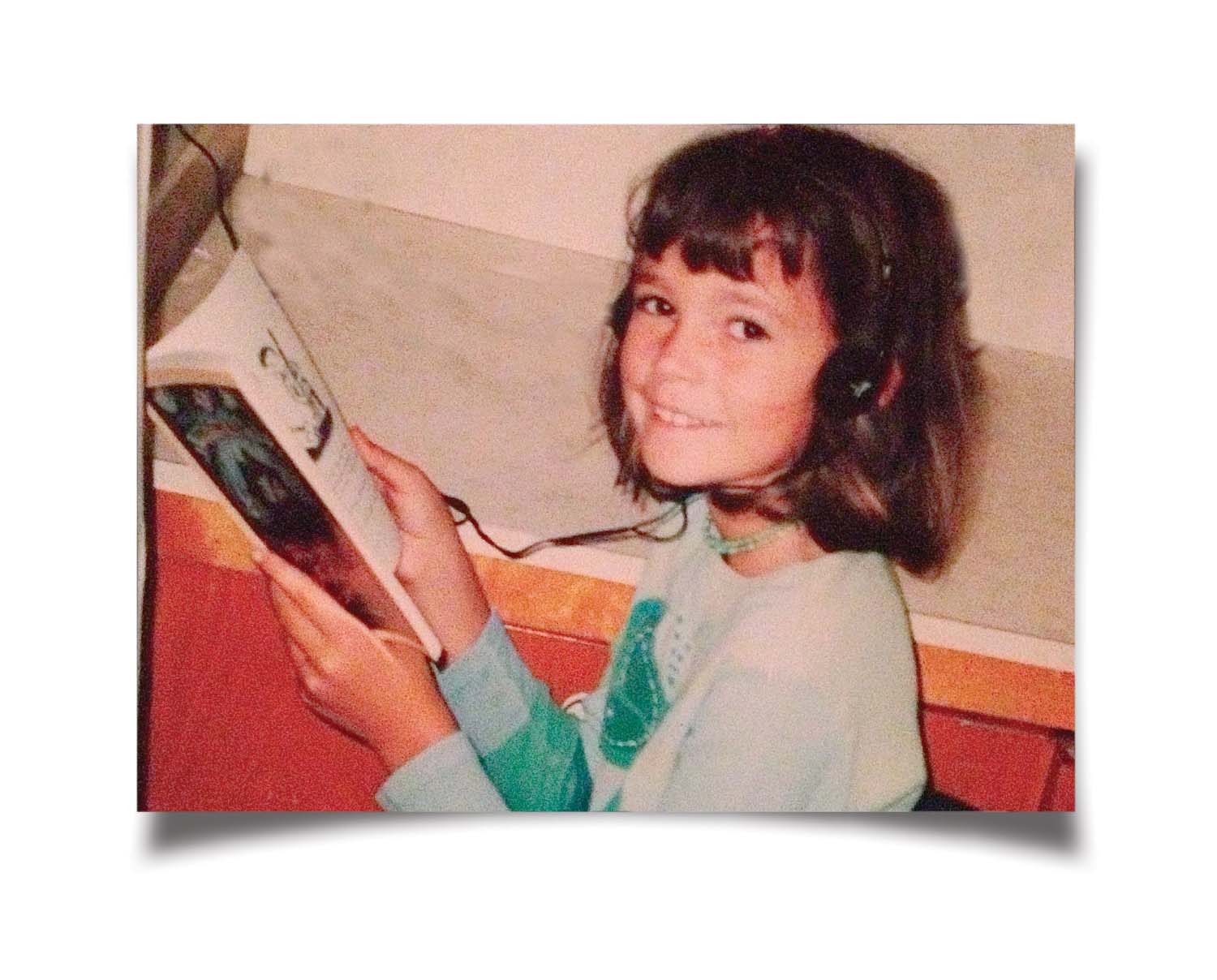

History major Tess Thomas ’14 knows a thing or two about making the best of a tough situation. Diagnosed with dyslexia at a young age, she didn’t know what the future held for her, but she did know one thing: she was going to keep moving forward.

When I was diagnosed at the age of 5 with auditory processing and visual memory disorder—a form of dyslexia—it would have seemed like a cruel joke to tell me that 16 years later I would be interning at one of the world’s leading publishers. And yet here I am, going into my final week at Penguin Group USA, surrounded every day by the thing I love most in this world: books.

Looking purely at the test results behind my early diagnosis, one might have predicted that my academic future was going to be bleak. I scored in the fifth and eighth percentiles on several basic evaluations, and I started first grade as the only student in my class still not yet reading. Sadly, many students who struggle early like I did are automatically considered slow or unintelligent—a label that often sticks throughout their academic careers.

I struggled to relate what I heard verbally with what I saw in written form. I could hear and pronounce the word “cat,” but no matter how many times I saw the letters “c-a-t” spelled out on a page, my brain did not connect them with the word I knew as “cat.” It didn’t mean I was any less intelligent than my peers, just that I learned differently than most. But “different” is sometimes perceived as synonymous with “worse,” and students with learning disabilities like mine are frequently neglected or made to feel dumb.

Fortunately, my mother advocated for me when I was too young to speak for myself. She ensured that my academic future would not be determined by a battery of test scores. She worked tirelessly to ensure I got the resources I needed to learn in my own way.

It wasn’t easy. I remember being overwhelmed at times that what was so natural for my older brother and my classmates was a colossal battle for me. Tears would spill over the pages of books I couldn’t read. My mom never gave up on me, though, and I learned never to give up on myself either. When school ended for my classmates, I continued on for two extra hours every day, practicing reading with special software designed to help students like me with phonological awareness, so I could relate sound structure to spoken words. Slowly, I became the student I am now, one who knows the value of hard work.

One of the reasons I adore reading so much is because it was denied to me for so long. When the jumble of letters on the page magically transformed into words, my voracious appetite for reading kicked in. I became a regular at our local bookstore and the school library, and reading has become one of my greatest passions. It seems only natural now to turn it into my profession.

Since coming to Johns Hopkins, I’ve had three internships in publishing—Teen Vogue magazine in New York, at an academic publishing house in London, and at Penguin USA in New York.

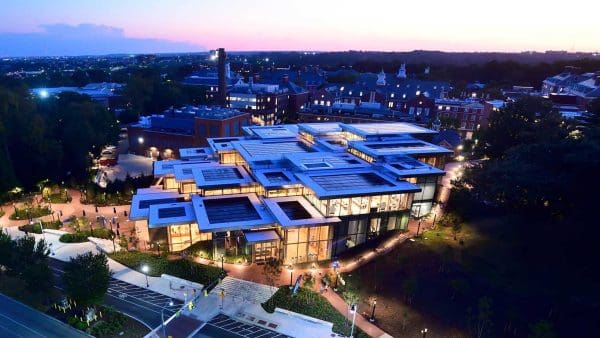

When I was accepted at Johns Hopkins three years ago, I knew it would help me professionally, but I had no idea it would open this many doors. When I graduate next spring, I will be well-positioned for my professional future.

The struggle I have had learning to read ultimately transformed me into the hardworking Dean’s List student I am today.