Bright winter sunshine streams through the Palladian window in Baltimore Clayworks’ studio, casting stripes of light across the blackboard and the row of Krieger School undergraduates who are balanced on three-legged stools, each of them in front of their own potter’s wheel.

“Anyone want to try wedging?” asks Matthew Hyleck, a potter and education coordinator at Clayworks, an educational ceramics nonprofit. Three students approach a table near the blackboard and scoop lumps of reddish clay onto the work surface. Slowly and with effort, they push and squeeze the clay, kneading it as if it were bread dough, preparing it for throwing. After the clay is wedged, the students share it with the rest of their classmates, and the room is filled with the pop and slap of flesh on clay as the students shape it into balls the size of grapefruits, per Hyleck’s instructions. Today’s lesson? To practice throwing a bowl on the potter’s wheel in preparation for the final class project: a series of kylikes—modern-day interpretations of the red-figure pottery drinking bowls created by the ancient Greeks between the sixth and fifth centuries B.C.

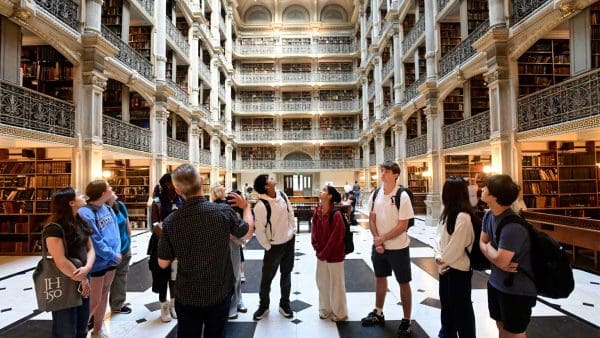

Sanchita Balachandran (center) and her students work on a potter’s wheel at Baltimore Clayworks.

Less than four miles from the Homewood campus, Clayworks isn’t a usual venue for a Hopkins course, but Recreating Ancient Greek Ceramics isn’t a conventional class. Instead, it is a new “hands-on course in experiential archaeology,” says Sanchita Balachandran, curator/conservator of the Johns Hopkins Archaeological Museum and lecturer in the Department of Near Eastern Studies, who teaches the class in collaboration with Hyleck. Fueled by Balachandran’s own interest in ancient techniques, the course is an attempt to get inside the heads of ancient Greek master potters who made the kylikes, which are some of the most intricately technical and aesthetically complex examples of ancient ceramics, and ask the question, How did they do that?

To find the answers, students immerse themselves in readings and lectures from art historians, classicists, ceramicists, and conservation scientists and in examination of kylikes from the Archaeological Museum’s collection of objects. Finally, through apprenticing to master potter Hyleck, they will recreate the experience of the ancient potter and the ancient apprentice. This includes all manner of hands-on activity, from learning to throw pots, to designing images, to experimenting with slipping and painting, to firing the ancient replica Greek kiln created from scratch by Balachandran and Hyleck.

“The idea is to be thoughtful at every stage,” says Balachandran. “To look at clay, make shapes, to choose images and paint, to go through the fire and kiln process, and to consider the final product. This leads to a deeper understanding of both the art and the object because when you go through the process, you get a visceral sense of how things got there.”

Throughout the semester, students post class summaries and reflections to the course blog and keep workshop journals filled with drawings and observations. At the end of the semester, they will also collaborate on a short written statement for “Humanities Connection,” a radio segment that airs on Baltimore’s National Public Radio station. Before that, however, come study, trial, and error.

Prior to their studio time, the students meet for a lecture given by Ross Brendle, a graduate student in the classics department. Kylikes were used as drinking vessels during symposiums, and Brendle discusses the traditional imagery—from heroic to risqué—used to decorate them. After the lecture, Balachandran asks students to consider what sorts of images would be appropriate modern representations of student life for their modern kylikes. Freshman classics and French double major Kelly McBride suggests decorating a kylix with the image of a fraternity party because “it’s like a modern symposium.” Dane Clark ’17, a Near Eastern studies and archaeology double major, offers Gilman Hall because “it is very symbolic of the university,” while Gianna Puzzo, a senior art history major who minors in museums and society, feels strongly about the inclusion of female figures on the kylikes—something that wouldn’t be found on the ancient renditions.

After the lecture and discussion, the students head into the Clayworks studio for the second half of class. After preparing their ball of clay for throwing, the students pause and watch Hyleck demonstrate how to throw a bowl. All eyes are on Hyleck as the clay rises and falls, thickens and thins under his hands. The clay is a ball, then a cylinder, a dome, a mushroom, a shallow dish, and finally, a bowl.

When the students try their hand at throwing, results vary. A few who have worked with pottery before create respectable vessels, but more than one student is frustrated with her results. “You’re putting more pressure on one hand than the other,” Elizabeth Winkelhoff ’18 gently tells her classmate Madalena Brancati ’18.

Ashley Fallon ’16 points out another challenge of the milk chocolate–colored clay: “It feels slippery, but it dries out under my hands.”

While they work, Balachandran and Hyleck ask students to pay attention to the process. “Did the piece collapse?” asks Hyleck. “When did it collapse? How thick was it?”

“Clay is a living material,” Balachandran reminds them. “There’s just something very alive about this material, and skill is needed to manipulate it.”

As the class winds down, students move to the sinks to clean up. In the next few weeks they’ll experiment with decorating their kylikes, trying out various tools including single cat whiskers and horse hairs to create images, and mixing various recipes of slip, the substance used to paint the pottery.

“As we’re going through, we’re realizing more and more what we don’t know,” admits freshman McBride, “but it’s very exciting. It’s a hands-on way to study the ancient world and go back in time. I feel like I can feel the hands of the potter.”