Photography by Jon Schroeder

One recent evening, space came down to Earth in the form of song on the Homewood campus.

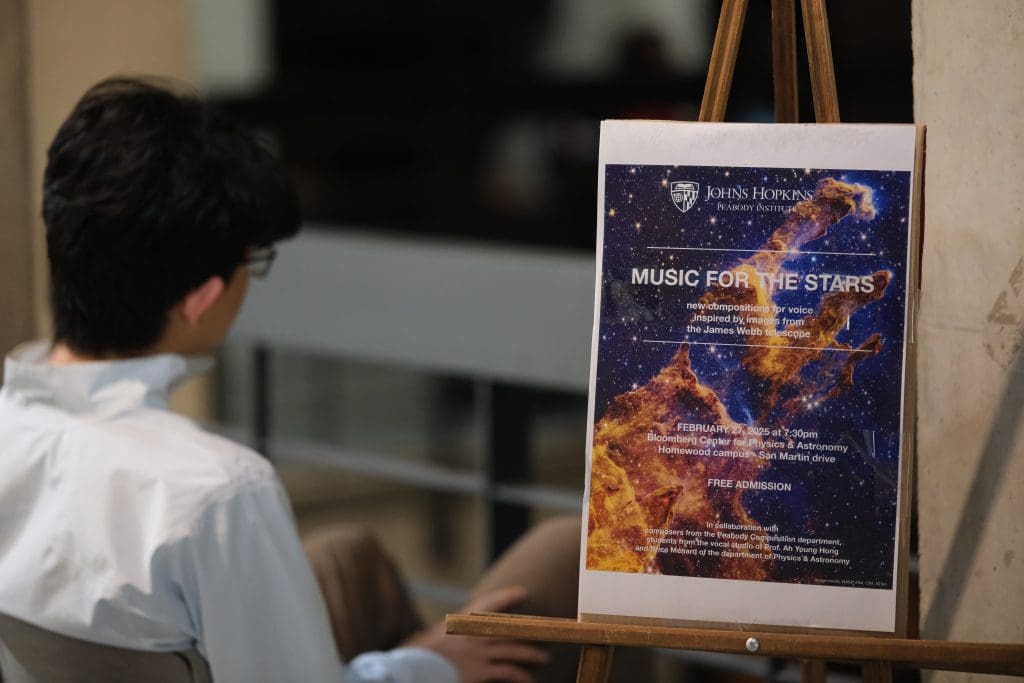

As an audience watched from the cavernous atrium of the Bloomberg Center for Physics and Astronomy, voice students from the Peabody Conservatory—scattered around the balconies above them—filled the space with original compositions inspired by images from the James Webb Space Telescope. Students in Peabody’s composition department composed the music.

“It was a beautiful example of a collaboration between arts and sciences,” said astrophysicist Brice Ménard. “I think there should be more art in our life and more interactions between artists and scientists. As scientists, it makes us pause and reflect and appreciate things we otherwise can easily forget on a daily basis.”

The February performance, titled Music for the Stars, was almost a year in the making and the second such event in the building’s rotunda. Ménard, professor in the William H. Miller III Department of Physics and Astronomy, selected six of the Webb’s iconic images, ranging from those within our galaxy to those on the other side of the universe. With colleagues, Michael Hersch, professor in Peabody’s composition department and Ménard’s friend, recruited six composition students to create vocal pieces in response to the images.

“Finding truly meaningful collaboration takes time and patience,” Hersch said. “It requires the building of trust, the exploration and alignment of hopes for the collaboration, and, ideally, some alignment of sensibilities, even if across seemingly unrelated disciplines. There is something inherently exciting about this when it happens.”

It was their friendship that made the collaboration possible. “I’m interested in music. He’s interested in science,” Ménard said.

Sparking curiosity

Once the composers and vocalists were selected, they entered an in-depth process of getting to know one another’s musical styles, said Ah Young Hong, associate professor in Peabody’s voice department. Composers familiarized themselves with each singer’s voice, comfort range, and flexibility; singers learned the composers’ sonic worlds and writing styles. Hong then coached them to transform that understanding into performance.

“These projects are meant to spark curiosity and allow each musician to explore their own potential and each other’s musical thought process. Creating new music, whether you are a composer or a performer, is as challenging as it is rewarding,” Hong said. “And it is one of the most exciting moments for me as a teacher to be able to guide them through this particular musical exploration.”

For the performers, the reverberant space of the atrium only added to the inspiring nature of the project, Hong said. For the audience, it helped knit together a unified experience from seemingly disparate parts. Unlike performances where the audience trains their gaze on a stage below, here audience members often had to look upward, as if into a sky full of stars. Exactly where the next voice was coming from remained a constant surprise.

Pushing forward frontiers

At times technical and avant-garde, the concert pushed the boundaries of music just as physicists tug forward the frontiers of science, Ménard pointed out. “We don’t get to hear those things on the radio. It’s good to be taken there; it’s an exploration,” he said.

“Working with colleagues outside of one’s immediate discipline is always a special thing,” Hersch said. “While the details may vary, we’re all trying to find answers to questions of meaning and meaningfulness. This is not the domain of our time alone. It is a human endeavor, and we in our own moment are simply attempting to continue the conversation.”

Student composers were Olina Kilbury, Emma Tucker, Noah Parady, Shuqin Li, Yuxuan Dong, and Aleksandra Wozniak. Vocalists were Kayleigh Sprouse, soprano; Sophia Sorrentino, soprano; Leisha Casimiro, mezzo soprano; and McKey Monroe, contralto. The performance was conducted by Carlos Meyers.