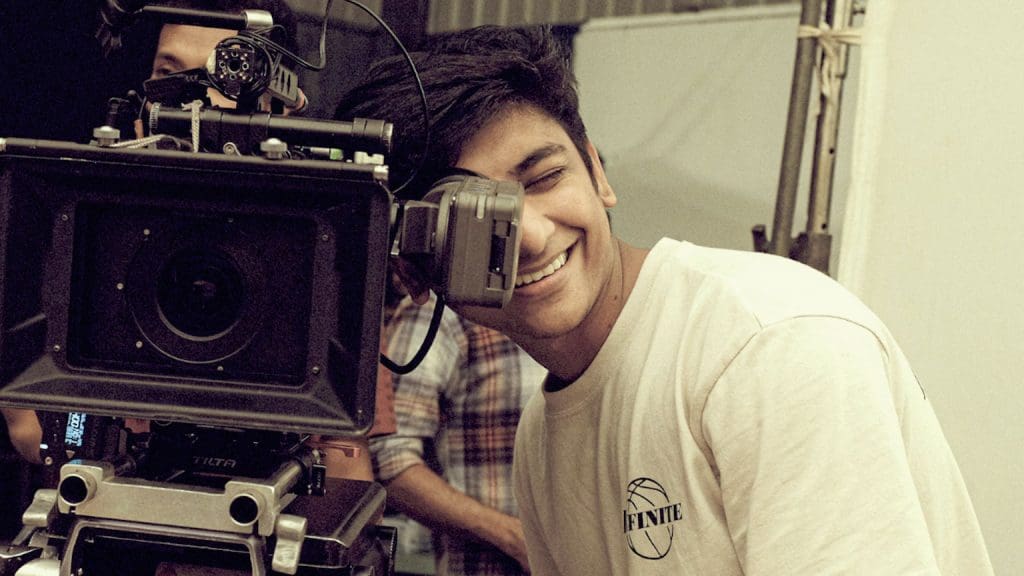

Last August, film student Ragheeb Moazzem was sifting through files for his job in Johns Hopkins’ medical archives. A box marked “Bangladesh” jumped out at him. He is from Bangladesh.

It was a turbulent time in his home country, which was in the process of toppling a 15-year fascist regime. And a harrowing time for Moazzem, who was unable to reach family during the internet blackout and had to watch from afar as people were shot in the streets.

So when he opened the box and found photos of Bangladesh’s 1971 war for independence from Pakistan, medical research notes, and a photo of a man receiving rehydration therapy—part of the backdrop of Moazzem’s life in a country where cholera can drain a body of its fluids within hours—he felt a kind of solace and a touch of pride.

“I found strength in the fact that we could overcome a war, so overcoming a fascist regime shouldn’t be that hard,” Moazzem says.

‘The Blue Death’

Cholera had long been a relentless presence in Bangladesh and in the Ganges River Delta generally, but during that 1971 war, when nearly 10 million Bangladeshis fled to refugee camps in India, it hit those camps even harder. It’s an unforgiving disease, killing about 50 percent of its victims within hours if left untreated. The mortality rates are even higher for children. Spread quickly through feces-contaminated water, it flourished in the crowded camps, which also lacked access to the only treatment available at that time: IV fluids.

Researchers from Johns Hopkins, the National Institutes of Health, and elsewhere had been working to develop a rehydration protocol, but it was not yet tested. When cholera attacked the camps, the refugees became unofficial research subjects.

The researchers’ treatment—a specific blend of water, sugar, and salts dubbed Oral Rehydration Solution, or ORS—proved almost miraculous. People recovered. Children lived. When the war ended and Bangladeshis returned home, they stopped dying of cholera there too. Positive public health outcomes across the entire country soared.

Some 30 years later, a three-month old infant was visiting a remote part of Bangladesh and contracted cholera. Far from any medical facilities, he was given ORS, and he lived. That infant was Moazzem.

No one person

Opening the box, Moazzem, who earned a master’s degree in film and media this month from Hopkins’ Advanced Academic Programs, didn’t quite understand at first what he was looking at. All he knew was that, at a low and scary point in his life, he was looking for something, for a sign of any kind. What he saw was the name of the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh, which is widely known in his country for its role in Bangladesh’s public health success story. It inspired him to plow ahead.

“It was like I found gold, but I didn’t know what gold was,” he says.

When the internet came back in Bangladesh, Moazzem spoke with his dad. After he confirmed that the family was safe, the conversation turned toward the country’s history with public health, and then to ORS specifically. Despite the solution’s ubiquity, and its pivotal role in his own existence, they realized they knew almost nothing about its origins. Maybe, he thought, doing more research would reignite his Bangladeshi pride during this dark time.

Poring over the Alan Mason Chesney Archives’ database on his lunch breaks, Moazzem learned that ORS, which seems so obvious in hindsight, was many decades in the making. Researchers had to set aside their belief that people with diarrheal diseases needed to be starved before food or fluids could be introduced. They underestimated how well cholera patients could absorb nutrients through the gut. They didn’t yet grasp the biological mechanisms behind glucose’s ability to improve the body’s uptake of water and salt.

And he learned about some of the doctors who developed the solution, which was confusing because he’d always heard that it was a Bangladeshi invention, and some of these doctors were Americans and Indians. Why wasn’t the full story better known? “It became clear that it was no one person that invented this,” Moazzem says. “Nobody kept an actual record of who created this thing or the sequence of events that led to ORS. Today, millions of people have lived, but nobody knows where it came from. I feel like it’s a shame, it’s such an important part of Bangladeshi history that is relegated to the sidelines.”

Sharing the journey

Being a filmmaker, Moazzem began to conceive of a movie that would tell the story contained within the box. Specifically, a documentary—a genre that had never held much interest for him until now. Not just a straight, talking-heads sort of documentary, however, but one that will mix interviews with stop-motion animation of the materials he found.

He’s begun to meet with the surviving researchers, including W.B. Greenough, David Nalin, and Norbert Hirschhorn. His initial fears that they would look down their noses at his lack of scientific background proved unfounded; instead, they’re eagerly sharing their stories. He’s come to appreciate the intricate path ORS had to travel before it could make its far-reaching and long-lasting imprint.

“The road to discovering this—making something simple—it’s so complex,” he says. “And I really want to highlight that in the film.”

Moazzem’s vision for his film was shaped by the pitching course he took with former Hollywood studio and production executive Sig Libowitz, who says Moazzem has a deeply compelling story to tell. The excitement of finding something significant in an old box, the personal connection to the history, and the path Moazzem took as he followed one clue to the next combine to create a powerful project, says Libowitz, director and senior lecturer of the graduate film and media program.

“His discovery has led him on an amazing journey already, combining his deep sense of family, country, and culture with a filmmaker’s eye for a great story and a fascinating cast of real-life characters,” Libowitz says.

“Ragheeb has a natural energy and charisma about him, and then you tie that into the passion he has for this project and what it means to him—personally and also as a citizen of Bangladesh, and a student of history—and then he sees the larger global picture of what this means. He did a beautiful job in his pitch, tying this complex picture into a very tight, emotional, personal, passionate story.”

Hope

Moazzem envisions that the film, which he expects to be two years in the making, will take viewers along for the same ride he’s on right now, uncovering the complicated story of a simple formula and simultaneously uncovering his own relationship to his complicated country. The journey may have started in a humble cardboard box, but it evolved into an unraveling of a long and intricate process that restored Moazzem’s pride in his country and his hope in humanity.

“Great ideas can come from the most unassuming places, and it’s often the simplest ideas that have the most impact in the world,” Moazzem says. “I realized that human collaboration is truly such a beautiful thing. I am a firm believer that we will be able to do unimaginable things as a group that collaborates together. People are divided, but I feel like even through the divide, people really can come together and create something that’s meaningful and change the world, because we’ve done it so many times.

“I was a nihilist for most of my life because I grew up in such an oppressive environment. But the older I get, the more I want to believe that that is not the case. Humans can do great things together.”