This really opens up a new window into those early days of the universe.”

This really opens up a new window into those early days of the universe.”

You can imagine how frustrating it is if you can’t find words, if you can’t...

Creating standards that are easily adoptable, like measuring cases and deaths for COVID, will be...

We’ve discovered millions of genetic variants that were previously not known across samples of thousands...

One of the most popular Christmas films in Ukraine is Home Alone, which has a...

See inside Professor Derek Schilling's office, which features a 1940s Philco radio console.

Student Daniel Habib studies social networks and teen vaping, or the use of e-cigarettes, after...

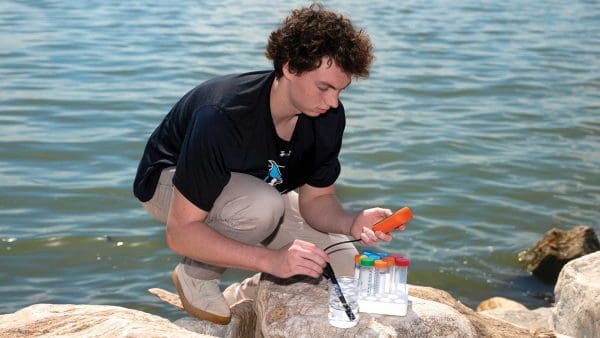

Molecular and cellular biology major Paul Gensbigler is helping to answer unresolved questions about the...

Academy Professor Alice McDermott discusses her latest collection of essays, What About the Baby.

Ten new books from Krieger School faculty, including books on growing up in Baltimore, the...

The course "The Grandeur of You and the Universe" helps students understand how basic earth,...

Three suggested books to read in spring 2022 from Krieger School faculty.