Lundquist, a national leader in research in sustainable energy generation from wind, joined Johns Hopkins...

Lundquist, a national leader in research in sustainable energy generation from wind, joined Johns Hopkins...

Lisa Deleonardis's new book covers her study of the 18th-century Santa Cruz de Lancha Jesuit...

Yuen Yuen Ang says China’s political economy today resembles America’s during the Gilded Age of...

Two Johns Hopkins faculty members teamed up to launch OneNeuro, an initiative that brings together...

Professor Sabine Stanley's first book, What’s Hidden Inside Planets?, is an easy-reading primer on the...

Henry Hung ’27 is using both his international studies and viola performance majors for his...

Three questions about taking a great photo from Homewood campus photographer Will Kirk '99.

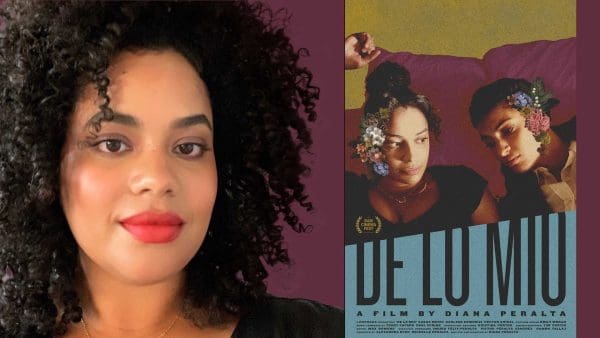

Diana Peralta ’11, who majored in film and media studies, is a Dominican American writer,...

A look inside "The Modern American Presidential Election in Historical Perspective," taught by Leah Wright...

Behavioral biology junior Alex Jeffords spent last summer interning at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and...

Alum Eric Fishel ’08 is an urban ecologist who introduces Baltimore city residents to overlooked...

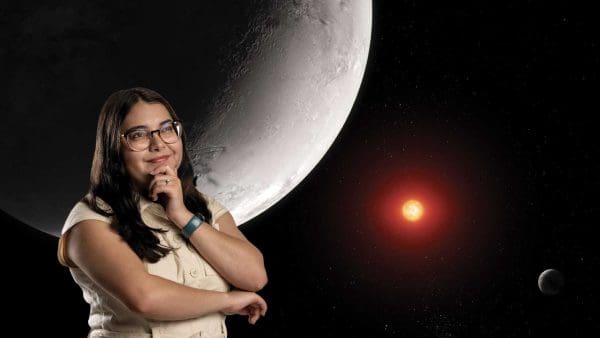

Doctoral student Junellie Perez is connecting models of geological evolution and observational findings to lean...