Students in the Public Health Studies program volunteer at Harriet Lane Clinic.

Students in the Public Health Studies program volunteer at Harriet Lane Clinic.

Krieger School students network in Hollywood with studio executives, television writers, and more during intersession.

In her new book, A Free Press, If You Can Keep It: What Natural Language...

Andrew Gordus’s lab uses two model organisms to study the cellular and genetic mechanisms that...

Julia Burdick-Will, associate professor in the Department of Sociology, talks about her beekeeping hobby.

Ethan Tan's research on Baltimore's Chinese community uses first-person stories to investigate how Chinese restaurants...

Anne Chiruvolu '10 gives her advice, as a small-animal veterinarian, on how to care for...

Bill Roche's Stagecraft class teaches students the hands-on approach to technical and theoretical elements of...

Art historian Irene Kabala ’01 PhD discusses her collection of between 1,000 and 1,500 artifacts...

Daniela Rodriguez ’24 uses textiles to express cognitive concepts, such as memory consolidation, in quilts...

Jennifer Lotz PhD ’03 was recently named director of the Space Telescope Science Institute.

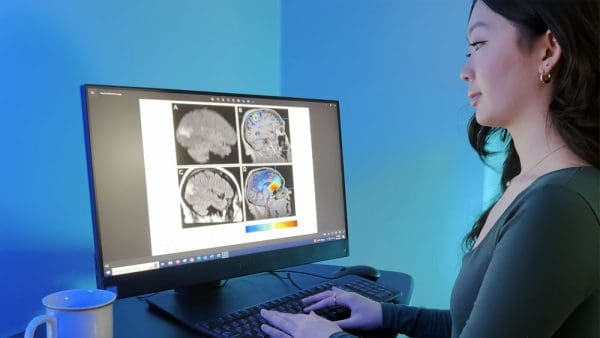

Junior Molly Zhao is studying neuroscience and economics. We spoke with her about her research...