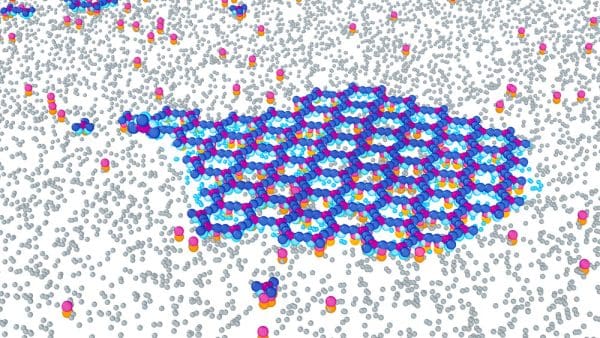

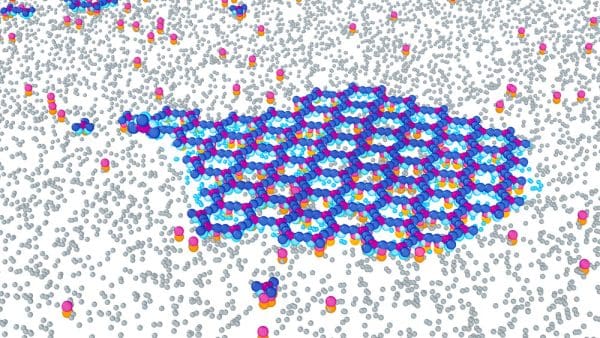

Margaret Johnson’s lab studies dynamical systems in biology, seeking to mathematically quantify how large molecules...

Margaret Johnson’s lab studies dynamical systems in biology, seeking to mathematically quantify how large molecules...

Students in the From Proteins to Living Art intersession course spent two weeks pipetting and...

Cherié Butts ’92 BS, ’97 MS is a medical director in the Therapeutics Development Unit...

Art historian Daniel H. Weiss, A&S ’82 (MA), ’92 (PhD), has returned to Johns Hopkins...

The chromosome associated with male development, which is the last mysterious piece of the human...

The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg Center, focused on policy and housing JHU's new School of Government...

Fall 2023 updates from Christopher S. Celenza, James B. Knapp Dean of the Krieger School...

Sarah Parkinson has dedicated her research to studying the behavior of organizations that are active...

William Egginton discusses his new book "The Rigor of Angels: Borges, Heisenberg, Kant, and the...

We ask Associate Professor Danielle Evans about her writing process and how she drafts her...

Yulia Frumer holds a professorship in East Asian science, but she also is an experienced...

Adam Rodgers, Faxon Director of Film and Media Studies, on his online comedy series Turf...