One hundred years after the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified, barring states from denying voting rights based on sex, the right to vote is still far from guaranteed. Deeply intertwined with that reality is one of the same issues that activists faced a century ago: the racism that kept many leaders in the shadows or worse; that shapes today’s faulty understandings of the people, events, and milestones of those years; and that continues to generate and accept wide-scale voter suppression.

Without African American women, the women’s suffrage movement would have been very different. But Black leaders are almost invisible in many retellings of that history. For them, the struggle wasn’t just about women’s right, or voting rights, but about rights for everyone: democratic rights. Their fight was one to hold the United States accountable to its own democratic principles, and that fight is ongoing.

Voting rights … were one part of a range of approaches that were intended to, yes, earn equality but also to earn dignity and to put Black women in a position to work for the interests of humanity.”

—Martha Jones

Martha S. Jones, Society of Black Alumni Presidential Professor and Professor of History, teaches and writes about how Black Americans have shaped the story of American democracy. Her book Birthright Citizens: A History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America explores the ways in which the struggle of the formerly enslaved to become citizens redefined American citizenship overall, and her just-published Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All tells the stories of African American women’s pursuit of power and how it transformed the nation.

Earlier this year, she spoke with Johns Hopkins writers about her books, the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, and the state of racism today. We share excerpts from those conversations here.

The Nineteenth Amendment was ratified 100 years ago, but voting rights are far from guaranteed even today. What is important about recognizing this centennial?

We live in a time where voting rights are being whittled away, attacked, and undermined. It’s hard to dive into voting rights questions in the 21st century without appreciating where they’ve come from. Among the long stories of our country is one in which voting rights have always been a battleground; they have always been buffeted about by politics, political whim, and factions—along with racism, xenophobia, and sexism.

The most important reason to remember the struggle around the Nineteenth Amendment is that it then lets us ask better questions about voting rights today. I’m very interested in the career and work of Stacey Abrams from Georgia. Some readers will be familiar with her run for the governorship and then, at the end of that campaign, her recommitment to registering voters in Georgia and getting out the vote in Georgia and, by implication, nationally.

I learned long ago that winning doesn’t always mean you get the prize. Sometimes you get progress, and that counts. This lesson has been drummed into me for most of my waking life. When it comes to voting in America, I certainly believe.”

—Stacey Abrams, from her book, Our Time Is Now: Power, Purpose, and the Fight for a Fair America

To me, it would be a mistake to understand Abrams as somehow a creature of the 21st century alone, or someone who comes of age post-Obama, or comes into the political fore after the undermining of the Voting Rights Act. I see Abrams as working in a much older, two-century-long tradition of African American women who have sometimes been inside, and sometimes been outside, the most conventional halls of power. Black women have developed their political analysis at the intersection of women’s rights and African American rights, and have always known that the Fifteenth Amendment [which barred states from using race when deciding who could vote] and the Nineteenth Amendment were not resolutions to the problem of voting rights; they just changed the terms by which African American women, in particular, engaged in the struggle for voting rights.

Many people today tell the story of women’s suffrage through a series of familiar names and events. But those represent one tiny segment of the full story.

Many Americans don’t know that the very first woman to speak in public about politics to a mixed audience was an African American woman in Boston in 1832 named Maria Stewart. Stewart had a short career as a public speaker in a city where radical abolitionism was on fire, where there was a thriving African American public culture. Stewart entered politics out of a set of principles that then informed African American women’s work around voting rights for a very long time.

First and foremost, she wanted Black women to examine the political landscape and analyze it with a sophisticated lens that came out of their own experience. She lamented and then decried how not only the insights but also the talents that she and women like her possessed were squandered and suppressed at a moment when Black Bostonians, and African Americans generally, strained to sustain themselves and to create themselves as a force in the nation’s politics. They were concerned about antislavery, they were concerned about civil rights, and Stewart says in essence, “So am I, and why is it that you’re keeping me out?”

She’s not someone who talks about voting. The story of women and the vote does not begin with women demanding the ballot. Instead, it began with a set of experiences, challenges, and questions about old limits on women, and with new urgencies that women felt. Even before white American women joined the antislavery movement, and discovered through antislavery activism their political identities, someone like Stewart was at the cutting edge.

It’s not the kind of story we expect, because we frequently hear that the story of women and the vote began at Seneca Falls in a women’s convention. Maria Stewart is a reminder that African American women were never, in significant numbers, part of those organizations that we associate with women’s suffrage historically. In 2020, we have a chance to understand how American women came to politics and power. To do that, we must ask where Black women were, what they were doing, and what they were saying. Stewart reminds us that not all women came to political power by way of a women’s suffrage movement.

Look at many of the most worthy and most interesting of us doomed to spend our lives in gentlemen’s kitchens. Look at our young men, smart, active, and energetic, with souls filled with ambitious fire… What are their prospects?”

—Maria Stewart, the first woman in America to address mixed gender and race audiences on the topic of abolition, in Boston, on September 21, 1832

Editor’s Note: This story first appeared with a photo labeled as 19th century activist Maria Stewart, but which actually depicted another activist, Charlotte Forten Grimke. There is no known existing photo of Stewart. We have numerous fact-checking methods in place to ensure the articles in the magazine are error-free, but we fell short of our own standards, and we deeply regret the error. We also recognize that this error is part of a larger problem of too easily accepting online material as valid, which clouds the meticulous work of generations of historians, and also falls into the long history of misrepresenting Black Americans.

You mentioned the Fifteenth Amendment that barred states from using race in deciding who could vote. What does its story reveal?

In the years leading up to the Nineteenth Amendment, there’s a terribly fraught bargain that circulates in Congress: “Let’s repeal the Fifteenth Amendment in exchange for passing the Nineteenth Amendment.” It was a bargain that would have permitted states to bar voters based upon their race while prohibiting them from barring votes based upon sex. The bargain hoped to keep all Black men and women from the polls, while opening them to white women.

That bargain fails, but remember that when African American suffragist and club movement leader Mary Church Terrell was calling for women’s suffrage, she also had to navigate a complex set of challenges. She did not find a partner in her push for Black women’s votes from white women suffrage leaders such as Carrie Chapman Catt and Alice Paul.

This was a lost opportunity, in my view. American women might have linked arms across the color line and changed the future of this country. Anti-Black racism is one of the most profound and lasting scourges this nation faces, and white American women missed a chance at the beginning of the 20th century to say, “We won’t vote until Black women can vote. We are for women’s suffrage and we are against lynching. We are for women’s suffrage and we are against the poll tax. We are for women’s suffrage and we are against literacy tests, etc.”

When we say that this road not taken was impossible or a pipe dream, it suggests that we still live by way of the assumption that racism always has, and racism always will, arbitrate political rights in this country.

In looking back at everything that was involved in ratifying the Nineteenth Amendment, are there lessons that we can apply today?

Racism is a women’s issue. White suffragists argued that segregation, lynching, and men’s disfranchisement were not women’s issues. Many took the view that Black women may not be able to vote, but it’s not because they’re women. And that means that’s not a concern for this movement. So the fundamental question: What do we mean by women, and who gets to define what women’s issues are?

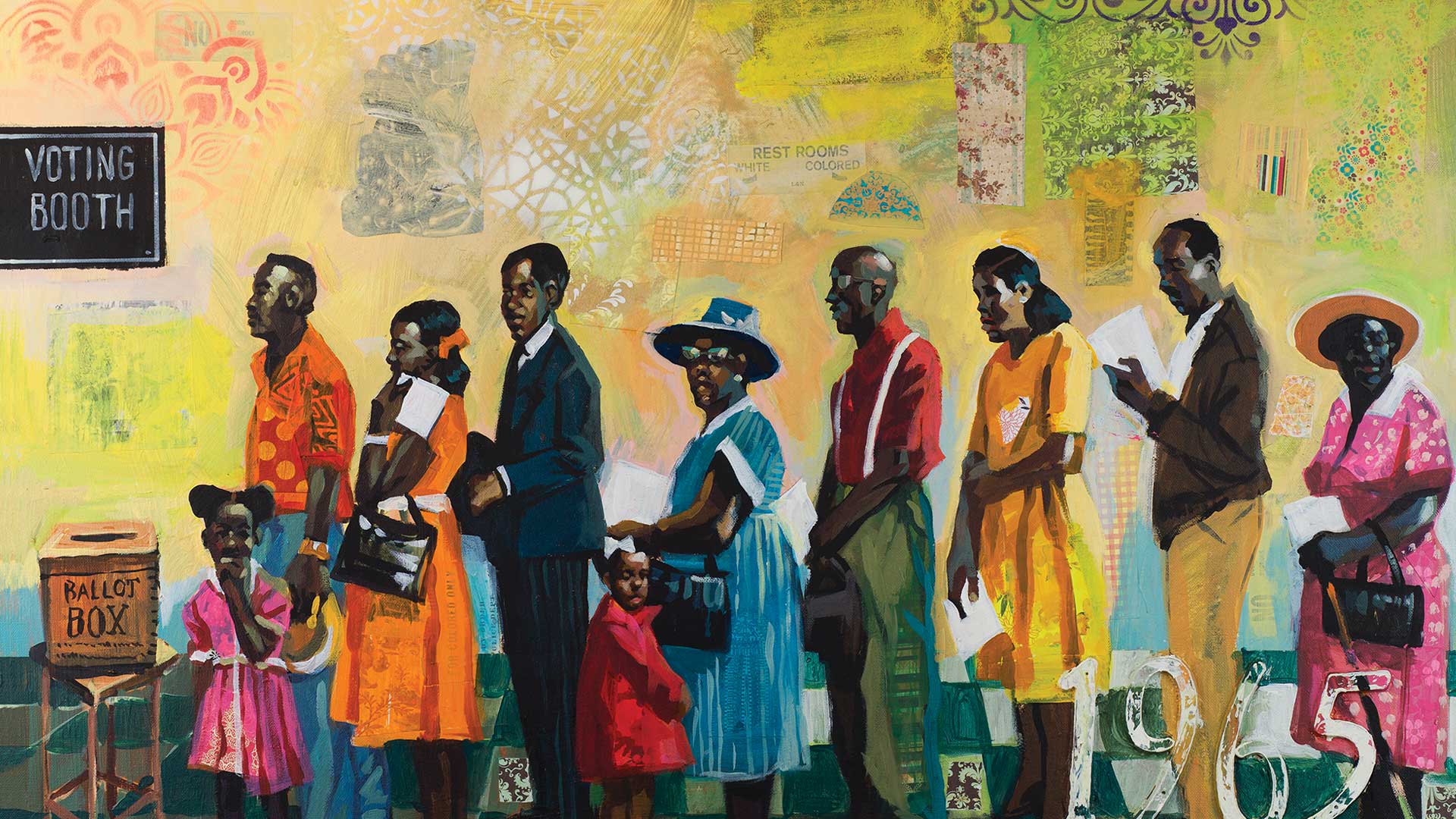

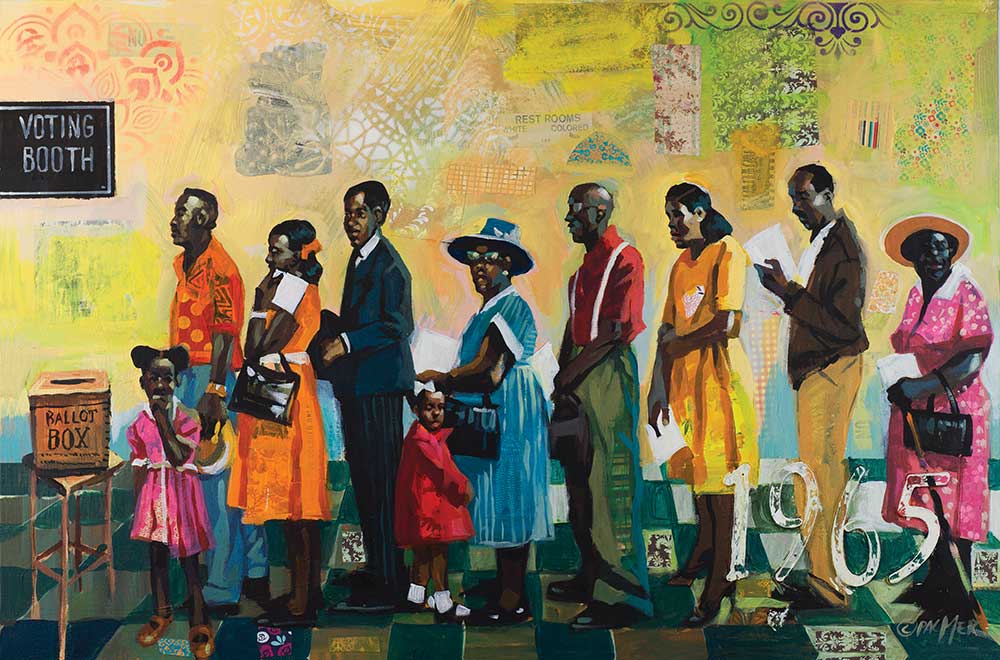

For African American women, Jim Crow’s poll taxes, grandfather clauses, literacy tests, and understanding clauses are what [civil rights activist] Fannie Lou Hamer and thousands of others continued to work on until they won passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965. These policies did not single out women, but they were policies, practices, and laws that disenfranchised women nonetheless. Sometimes a women’s issue also affects men. There have existed between American women a philosophical divide in which African American suffragists sought their political power—including the vote—to win human rights. They sought the vote and office holding and insider status in party politics not simply to empower women. They worked to see to it that all American women—including Black women—would be empowered to win human rights. This means that Black women worked for the betterment of all humanity.

Nobody’s free until everybody’s free.”

—Fannie Lou Hamer, addressing the National Women’s Political Caucus in Washington in 1971

Tell us about Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All.

It is a history of African American women’s politics from 1820 to 2020 with a focus on the vote. It’s called Vanguard because my view is that African American women are the first—and continue to be the most committed—thinkers and activists toward a human rights vision; toward a vision of women’s rights and its interest in all humans. They have always rejected racism and sexism and set a high bar that has been difficult for us as a nation to reach.

The book follows Black women in their political lives and political organizations through abolition, the Fifteenth Amendment, Jim Crow, the Nineteenth Amendment, to modern civil rights with the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and ends with Stacey Abrams, whose work embodies the values of Black women.

Once readers recognize that there were figures going back 200 years who embodied the best of our ideals in the 21st century, they will recognize that Black women really were showing us the way all along. It has taken us a long time to catch up.

I’m excited because it also reflects a half-century of excellent scholarship on women’s politics by dozens of historians. The book stands on the shoulders of three generations of women’s historians.

Can you expand on the essential connection between voting rights and human rights that you draw in Vanguard?

As I started to read through the commentary, the speeches, the writings of Black women, particularly those at the end of the 19th and the start of the 20th century, there were words they used that at first surprised me. Words like dignity and humanity. I began to learn that those words were reflecting a set of principles, values, and objectives that Black women in particular embraced and worked toward as political thinkers and as activists. There was more at stake than the vote. Voting rights, in their view, were one part of a range of approaches that were intended to, yes, earn equality but also to earn dignity and to put Black women in a position to work for the interests of humanity. It was ambitious, and Black women led pointedly with a critique of how both racism and sexism too often perverted and distorted and otherwise degraded American political culture.

What lessons are you seeing from this vanguard of women that could help inform the grassroots protests happening across the country right now?

Black women have known all too well the capacity of the state both to enact violence upon them and to turn away and fail to punish the perpetrators of that violence. Black women activists consistently demanded that they be free of violence, and from the specter and threat of violence in their daily lives. Today, as we mourn and grieve and rage at the deaths of Black Americans like George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, the women I write about would recognize both that sadness and that outrage because the ever-present threat of violence also constrained their lives. Political history teaches us that Black women in public and Black women in politics risked encounters with a robust and vile brand of racism that questioned their very womanhood.

This moment is an unusual intersection of anti-racism protest, assertion of voting rights, and a pandemic.

During Baltimore’s primary election in June, we saw people, our neighbors and community members, at the polls. That same day, Baltimoreans were in the streets. For that moment, there didn’t appear to be a contradiction between a politics of the polls and a politics of protest. That resonates with me as reflecting the rich complexity of the African American political tradition. It is varied and it is diverse.

Casting a ballot and supporting a demonstration are consistent parts of a whole. These scenes are especially poignant during a pandemic in which Black Americans are documented as both contracting and suffering the fatal consequences of COVID-19 in disproportionate numbers. Black Baltimoreans, in particular, took their lives in their hands, whether they were standing in crowded polling lines for long periods, entering crowded polling places, or protesting in the streets. American democracy demands nothing less of Black Americans than that they put their bodies on the line to hold this nation to its ideals, and to hold it accountable. It’s quite a remarkable moment.

You have been named to lead a new initiative charged with examining the history of racial discrimination at Hopkins. What does academia do to become anti-racist?

In my spaces in academia, including my department at Hopkins and my professional organizations, I need to hear more than “thoughts and prayers.” I’d like us to tell the story; I would like to hear told out loud precisely how we got here. We must understand and own how our institutions—their leadership and their culture—produced the unjust and deeply disappointing state of affairs that we face today, whether it’s the underrepresentation of Black faculty, or unabated incidents of microaggression.

I’m a historian, and I think the past matters. I’m also a storyteller, and it’s important that we tell a fuller story about our institutions, one that acknowledges, admits, and explains through research and data how structurally and culturally racism and discrimination have persisted, despite the efforts that have taken us from civil rights to diversity. The cost of this failing is plain, both in the hashtag confessions of Black faculty and students, such as #BlackintheIvory. It is also in the statistics and the demographics of our institutions. I do not encourage immediately moving to: Here’s what we’re going to do. Before we determine what we must do, we must examine what we’ve done, or not done. It is time for some truth telling about how our institutions and our nation have ensured racism’s persistence.

Hear more from Martha S. Jones

President Ronald J. Daniels and Jones have a conversation about her forthcoming book, Vanguard, which is a history of African American women’s pursuit of political power and how it transformed America.