The familiar notion of libraries retains a powerful hold on the public imagination: dimly lit rooms with floor-to-ceiling stacks, protected by solicitous librarians.

“Books can sit on shelves and collect dust,” says Earle Havens, director of the Virginia Fox Stern Center for the History of the Book in the Renaissance. “And that’s not a bad thing. They need to be protected from the vagaries of the world.”

Yet such images quickly dissipate as Havens opens a locked drawer and removes “ephemera”—several hundred single-sheet imprints and broadsides dating primarily from the 16th and 17th centuries—belonging to one of the university’s most vital research collections.

While the Stern Center has embarked upon a robust program to digitize these documents and a vast number of other treasures, the actual sheets impart a startling imaginative power as you examine them closely. You hold in your hands particular and tangible moments in the journey of scientific progress, created when the printing press was a “new” technology.

Havens’ vision for the Stern Center is to inspire scholars, antiquarian book collectors, and students to see archives as a dynamic enterprise that encompasses not only digital dissemination, but a tangible and tactile experience of rare books and the secrets they hold. For humanities scholars and students at the Krieger School, objects such as those in Johns Hopkins’ early printed ephemera collection present untapped sources of knowledge, and even pave the way for unique career opportunities.

A Force of Nature

“All of human knowledge was—until very recently—entirely dependent on the physical production, circulation, and consumption of these objects,” observes Havens, who also teaches in the Department of Modern Languages and Literatures. “So you cannot separate the object from its existence in the world, in the life of the mind, and in public discourse.”

“When you look at something that was printed in 1503, it just brings the whole dimension—both the author and the reader come alive in that book,” observes Mark McConnell, BA ’75, who is deeply enmeshed in the activities of the Stern Center as an associate research fellow.

When you look at something that was printed in 1503, it just brings the whole dimension—both the author and the reader come alive in that book.”

—Mark McConnell ’75

These explorations of Renaissance books are enriching scholarly research at the Krieger School, and sparking powerful interdisciplinary collaborations. They are also blazing new career paths for arts and humanities students at all levels.

“Earle is a force of nature,” says Erin Rowe, Vice Dean for Undergraduate Education at Johns Hopkins, and a professor in the Department of History. “He is bringing faculty and graduate students and undergrads into his world in a way that I think is not visible to a lot of my colleagues.”

The Stern Center’s home at Hopkins’ Evergreen Museum and Library—located just a few minutes north of the Homewood campus—is also gaining a reputation as a thriving and nurturing community, where proximity to fascinating objects spurs collaborations and friendships.

“The physicality of the object has, for lack of a better term, a magic to it,” says Martin Michalek, a recent Stern Center Curatorial Fellow and PhD candidate in the Department of Classics.

Building Bridges with Books

A knack for creating meaningful connections between scholarship and curatorial practice has led to Havens’ success as an ambassador for the Renaissance books and manuscripts in the collections of Johns Hopkins’ Sheridan Libraries.

His impressive scholarly publications are matched by a skill in forging links between rare books and contemporary technology. Indeed, the Stern Center’s foundations can be traced to Havens’ essential role in the groundbreaking Archaeology of Reading (AOR) collaboration between Johns Hopkins, Princeton University, and University College London.

The AOR project used digital technologies to make valuable annotations inscribed in books owned by John Dee and Gabriel Harvey—renowned Renaissance intellectuals—fully accessible and digitally searchable by scholars and the broader public. As an experiment to democratize scholarship and expand its reach, the award-winning Archaeology of Reading project was an unalloyed success. Yet the annotations in the AOR also laid bare a dense network of rich connections between early modern readers and texts that continues to yield fresh insights for researchers, including a recently published book.

The Stern story

The Stern Center is named for Virginia Fox Stern, a distinguished Renaissance scholar and book historian whose most celebrated work centered on Harvey’s writings and career. She was also a pioneer in breaking down the significant barriers for women engaged in scholarly research in the mid-to-late 20th century.

“Virginia Fox Stern was very active in the Renaissance Society of America,” notes Havens. “It was one of the earliest academic societies that was extremely open and welcoming to women.”

When her son Jolyon Fox Stern read an article about Johns Hopkins’ role in the AOR effort, he sought a way to advance the work further. “It has been one of the joys of my life to make it possible for my late mother’s extraordinary scholarship to be recognized at Johns Hopkins University by creating a center for study in her name,” says Stern. “Earle Havens has honored her and created a haven for study she would be very proud of.”

The Evergreen Museum itself is suffused with a book-collecting culture nurtured there by the Garrett family in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and it is home to many of the most important Renaissance-era books in the Sheridan Libraries’ collections. So it is a perfect stage for the Stern Center’s wide-ranging program of interdisciplinary scholarship—including an annual lecture series, international symposia, and master classes based on Hopkins’ unique collections of rare books covering all manner of subjects from literary forgery to early East Asian imprints.

Actively engaging with books

Havens says opportunities to work closely with Hopkins’ early rare book collections are the key attraction: “It’s all about the books, right? It isn’t about simply creating access to a text or providing researchers with bibliographical information. We actively engage with students and scholars in order to breathe new scholarly life into very, very old books. We put a 1,000-year-old illuminated manuscript in front of a first-year undergraduate and ask them ‘What do you see?’ The impact is palpable and emancipating.”

Success in attracting scholars to Hopkins is already apparent. “We have more applications than we can accept for fellowships,” he continues. “We are even getting interest from students who don’t normally work in earlier historical periods.”

Interdisciplinarity is an essential element in this activity. The breadth of Hopkins’ rare book collections ensures that every one of the Krieger School’s humanities departments have an interest in its holdings. Michalek observes that the Stern Center’s focus on research on rare books across disciplines “put me in connection with other people across the humanities.” While many of these departments are housed in Gilman Hall, he continues, “We’re on different floors. You’d be surprised how few people want to go up and down to different floors. The way that the Stern Center is designed is… you bring them all together, and you see what comes out of it.”

Building a Curatorial Culture

Curation holds a central place in Havens’ vision and practice. Like the current curatorial fellows, Havens’ fascination with rare books began in graduate school, inspired by years of working with curators at Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

“I walked up to the security guard,” Havens recalls, “and asked how I might begin to work with the collections. He called down to various curators’ offices until Stephen Parks, curator of the Osborne Collection of early modern manuscripts, answered the phone.”

Over the next six years, curatorship became Havens’ passion, and it was no mere apprenticeship. Mentors such as Parks provided avenues into the antiquarian books trade, as well as opportunities to work on exhibitions and publications. Close bonds of fellowship forged with other graduate students working at the rare book library deeply enriched his graduate school experience.

“I wanted to recreate that atmosphere at Hopkins,” says Havens.

A culture of fellowship

One way to do so: annual curatorial fellowships for Johns Hopkins graduate students who want to integrate the history of the book more deeply into their scholarship.

Ambra Marzocchi, PhD ’23, says the 2022–23 curatorial fellowship she received as she researched the reception of classical texts in colonial Mexico and elsewhere in the New World was transformational.

I discovered a new field thanks to the Stern Center: I could join

my classical studies with Renaissance studies, and also add to that the history of the book.”

—Ambra Marzocchi, PhD ’23

Marzocchi came to the Krieger School with a focus on philology, but, she says, “I discovered a new field thanks to the Stern Center: I could join my classical studies with Renaissance studies, and also add to that the history of the book.”

Talks by experts outside academe—including antiquarian booksellers and paper conservators—proved especially valuable. “Thanks to the Stern Center, we learned a lot about the mind that you have to have if you want to be a good curator,” Marzocchi continues. “The curator is not only a conservator of objects, but he or she also needs to be able to transmit to the audience what the significance of these objects is.”

Applying the knowledge

An exercise in which the Stern Center’s curatorial fellows spend budgeted funds at New York’s annual International Antiquarian Book Fair illuminates just how to apply this new knowledge. “It was a terrific experience,” says Marzocchi, “because we had a responsibility to make a choice for our institution’s collections.”

Immersion in curatorship presents an opportunity for everyone involved in the center’s work. In 2017, when the Sheridan Libraries acquired the foundation of its “Women of the Book” collection of rare books on early modern women, Erin Rowe, whose work focuses on early modern religious culture in Spain, was excited by its resonance with her own research interests.

Havens seized an opportunity for a deeper collaboration. “He started talking to me about it right away,” says Rowe. “He’s always looking for partners with the Stern Center, and he’s extremely generous.” As the “Women of the Book” collection grew from 400 objects to more than 1,000, Rowe and past Stern Center Fellow Board member Aaron Hyman were along for the ride.

“Earle would get offered new things,” she says, “and he would always ask: ‘What do you think about this? Should we have it?’ So we were always in conversation about the things that were being added.”

Material Energies

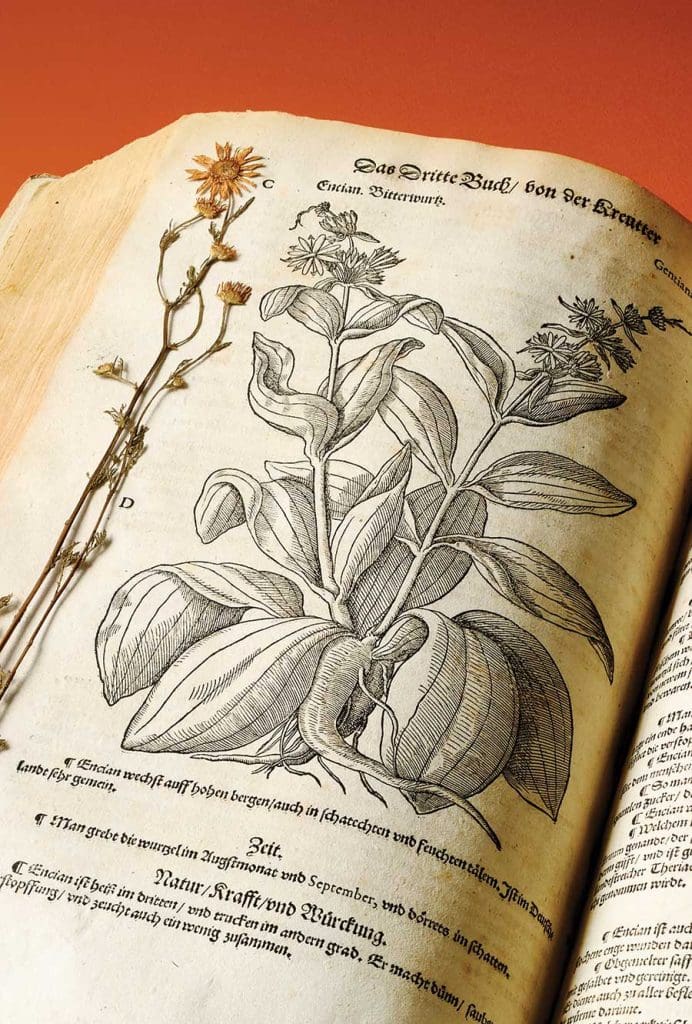

in the “Grand Mattioli,” a 16th-century botanical text.

When Martin Michalek says that physical rare books manifest a kind of magic, he puts his finger directly on an indispensable source of the center’s energy.

For instance, scrutinizing Renaissance books and curation translates well into classroom settings. Havens says that the fresh gaze of undergraduates—such as those in a First-Year Seminar on “Books, Authenticity, and Truth” that he has taught with Christopher Celenza, James B. Knapp Dean of the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences—often reveals hitherto unnoticed aspects of these books.

As a class was thumbing through a 16th-century botanical text known as the “Grand Mattioli,” Havens recalls that “an undergraduate spied something deep in the book’s gutter—a dried flower that matched the flower in the very same opening. That could well be a 450-year-old flower.”

Another undergraduate in a rare book class noticed a mosquito “caught into the mash of the paper” in an unbound 16th-century copy of Copernicus’ treatise De revolutionibus. “Are these going to change the world? No. But they create opportunities for students and scholars to feel like they’re a part of knowledge production,” says Havens. “Because they are.”

Creating new paths

Becoming part of the Stern Center also broadens the career paths available to humanities students at Hopkins. Havens speaks proudly of Stern fellows who can now envision pursuing curatorial careers, and others who will integrate rare books into their teaching after being in the Stern Center’s orbit.

As a dean of undergraduate studies, Rowe says that rare books—and the training required to unlock their secrets—has turned out to be a “viable career path” for Hopkins students at all levels.

“Having access through somebody like Earle to that world is very powerful training. It’s training from a historian’s perspective. You learn how objects are made, which is really important, because we’re never taught that. But also I see it as professionalization. I want my graduate students and undergrads to recognize that this is what you can do with a humanities degree.”

Investing in knowledge collection

Rare books also have lured Krieger School alumnus Mark McConnell to the Stern Center to pursue his interest in Renaissance texts and the business of printing them. He describes falling in love “with the story of the recovery of classical literature” and building a rare book collection of his own—mostly of Renaissance Greek imprints. As he wound down a successful career in international law, McConnell was told about a fascinating collection: the business records of a mid-16th-century printer in Antwerp.

The archive is “a miracle of history,” says McConnell, and it offers astonishing detail of the business models of one of the producers of the materials that are so highly prized by researchers and antiquarian collectors. “You start looking at business strategy,” he continues. “How do you decide what to print? How do you decide how to publish it? When did he illustrate a book?”

McConnell soon brought his expertise to the Stern Center. “He’ll bring books from his collection here and give a master class to the students from his own collection,” says Havens.

Immense intellectual capital was required to reclaim lost classical literature, and deserves study in its own right. So McConnell says that Havens’ desire to prioritize support for graduate students, in addition to lectures and symposia, “rang bells with me” as they talked about philanthropic involvement with the Stern Center.

Playing to Strengths

Keeping a tight focus on rare books is fundamental to the Stern Center’s success. Its emphasis on the history of the book in the Renaissance is embedded in the center’s name.

“If you just have a center for the history of the book in general,” quips Havens, “it could be about anything.”

The Stern Center has kept pace with a larger trend of digitizing vast swathes of its collections for access by researchers around the world. The wisdom of digitizing became apparent as a global pandemic shut down universities and archives for a few years.

“In the Middle Ages, they chained the books to the shelves,” says Havens, “and you literally had to cross the Alps to go to the library to read a manuscript. It’s not a bad thing to think about these things in reverse.”

A distinctive collection

A pride in remarkable individual objects—such as translator Richard Eden’s annotated translation copy of Peter Martyr’s groundbreaking 1533 account of global exploration, Decades of the New World—bubbles over in Havens’ conversations about his work.

Yet his curatorial sensibility inevitably directs the conversation back to a broader view of Stern Center activities that builds upon the acknowledged strengths in Hopkins’ comprehensive research holdings. He sees the treasures in the university’s rare book collections in broad areas—in the arts and sciences, in literature and architecture—as a foundation also for building new collections in literary forgery, women’s spirituality, and ephemera that align with those strengths.

“It all comes back to the collections at Hopkins,” says Havens. “And the distinctiveness of those collections.”