This is the first in an occasional series that highlights research and scholarship of Johns Hopkins faculty whose work examines issues around racial inequity, discrimination, and race relations.

It’s no secret that racism is alive and well in the United States. Perhaps one of its most insidious strongholds has been in the real estate market, where for decades, Blacks have faced barrier after barrier to achieving one tenet of the American dream: homeownership.

Nathan D. Connolly, tenured faculty in the Department of History, has spent the better part of his career uncovering inequities in the U.S. housing arena through books, publications, and a digital effort to reveal the long-lasting effects of the practice called “redlining”—the discriminatory practice of denying financial services to residents of certain areas based on their race or ethnicity.

“I saw the project as a way to get scholars to do some comparative work,” Connolly says. “If they could download documents covering multiple cities to learn more about how, in common practice, discrimination in housing has worked, we might gain a deeper understanding of why the housing landscape in the U.S. looks the way it does now.”

Connolly’s deeper explorations of the historical dynamics of real estate are what make his work distinctive. His contribution to Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America, a collaboration of dozens of researchers around the country that has helped to expose some of the roots of racist housing practices, demonstrates what’s most important to him: finding data, publishing it in a form that activists, residents, and scholars can easily get at, and providing a rich historical context for why the data matters.

A Handmaiden to Racial Segregation

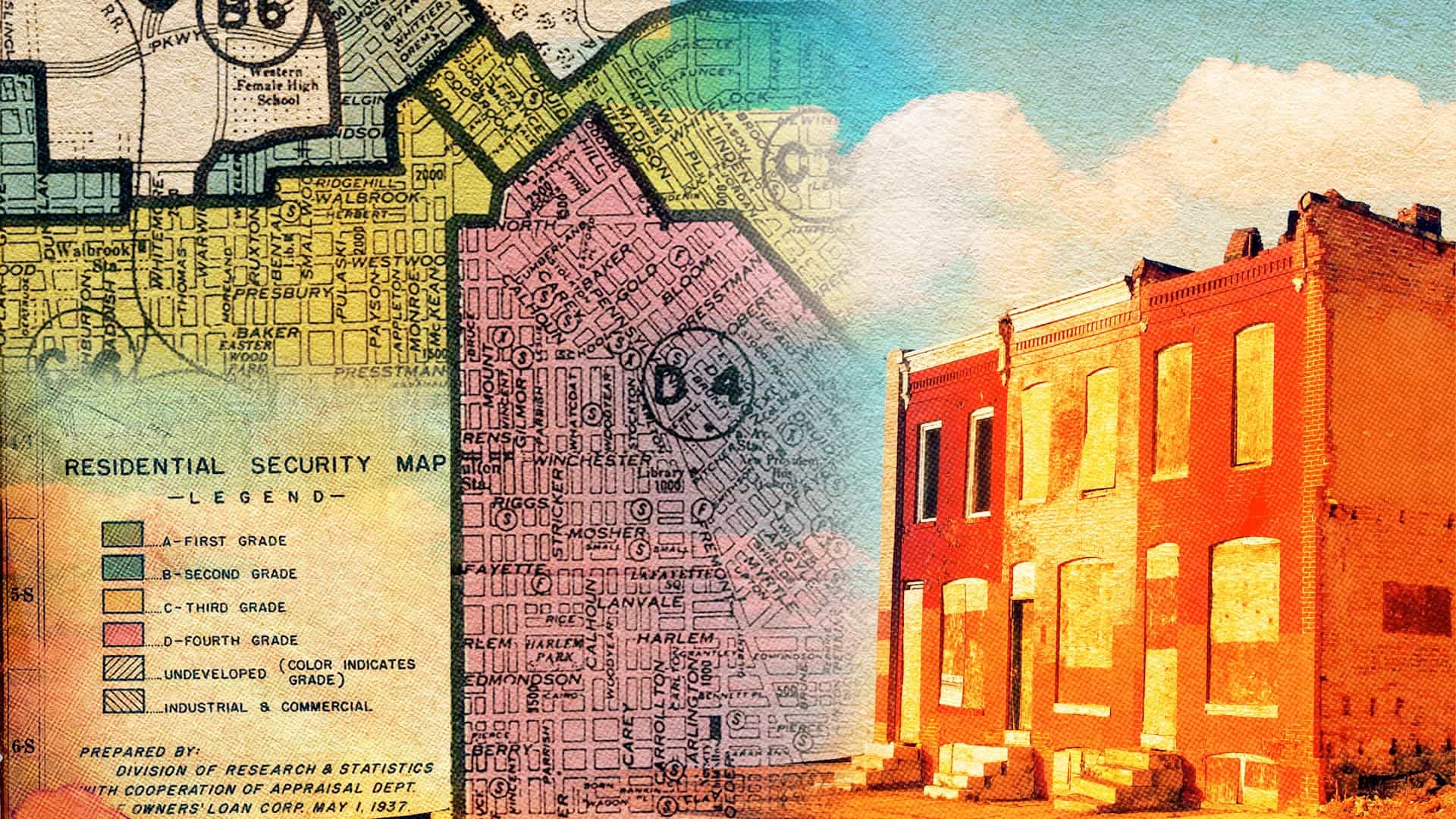

Mapping Inequality digitizes archival maps and records created by federal government officials and private lenders during the Great Depression. Those documents show the grades assigned to neighborhoods based on home values. When applied to areas seen as the least financially viable, those maps formed the basis for “redlining.”

A common practice for doing business throughout the middle of the last century, redlining was a handmaiden to racial segregation, a phenomenon that has limited the ability of African Americans to move and live freely. It also denied them a prime opportunity—homeownership—with which to build wealth.

Redlining sits in the middle of the grievous historical continuum of Black housing, one that starts when whites provided enslaved African Americans with only the most ramshackle of shelters. Post-Civil War, Blacks saw owning property as one way of asserting their status and humanity. To own something represented a move toward freedom. Property rights were seen as a step toward full civil and human rights. In spite of legal roadblocks and outright racial violence, Black property ownership grew steadily up till about a century ago.

In 1920, nearly 50 percent of Black people owned property. That was the high-water mark for Black ownership. We’ve been trying to get back to that percentage since the Great Depression.”

—Nathan D. Connolly

In 2020, 44 percent of African Americans were property owners, far below the 73 percent rate for whites.

Long-existing barriers to Black homeownership are largely responsible for the yawning wealth gap between Blacks and whites, with the latter owning eight times the assets—property or anything else—as the former. And those barriers have proven hard to dislodge. Very little progress has been made in closing that gap during the last 50 years. What’s more, Blacks who do own homes tend to lose them at a much higher rate than whites during economic downturns, as happened during the recession of 2008–09.

Ownership doesn’t solve all problems, either. Disinvestment in African American communities by governments and landlords continues to diminish the value of Black-owned properties within their boundaries. Over several generations, the bulk of private and public dollars, as well as tax breaks, have become concentrated in white neighborhoods. “Capital will find a way to flow to the most advantaged,” Connolly says. “Because of this lack of progressive—rather than predatory—investment in once-redlined neighborhoods, Black homeowners aren’t allowed to develop equity in the same way people in white neighborhoods are.”

The Depression era ranks as a historical bellwether in this longtime trend. To help people hold on to their homes, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt founded the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, or HOLC. To safeguard the loans being made to keep homeowners (and banks) afloat, the HOLC and the Federal Housing Administration rated each neighborhood an A, B, C, or D. Colors corresponded to each grade, with the D regions outlined in red—“redlining.” The government’s good intentions—keeping people in their homes—were predicated on confining “risk” to D areas. Most often, “risk” became synonymous with Black people.

Though the founding of the HOLC is often deemed the starting point for official redlining, the practice has long dogged African Americans—something that has inspired scholars to contribute to and mine Mapping Inequality. Some cities, including Baltimore in 1910, passed their own ordinances legalizing housing segregation and forms of redlining. Black people forced to live in marginal neighborhoods had little ability to borrow.

“You can see from looking at areas of Baltimore in the 1930s that neighborhoods like Sandtown, where Freddie Gray would eventually live, had a previous history of redlining,” says Connolly. “People were effectively told where they could live and where they couldn’t. Segregation means that people have no control over where they will live.”

The concept behind Mapping Inequality first began to form in 2012, when scholars at four universities, including Johns Hopkins, gathered to discuss how to make those maps—along with area descriptions, government documents, and ongoing scholarship—accessible to people living in areas affected by racially discriminatory housing practices.

Scholars at the University of Maryland, Virginia Tech, and the University of Richmond were integral in untangling the logistics and setting the scope of the project. Connolly played a lead role in providing a historian’s sense of context, especially in the years before the site’s rollout in 2016 and early on in its existence. He helped promote the site among scholars and served as a lead author for the website’s text and related publications.

Robert K. Nelson, a historian and director of the Digital Scholarship Lab at the University of Richmond, which maintains the Mapping Inequality site, said “Nathan’s input was especially important when it came to establishing the broader context: What information should we highlight? What can we convey via the use of archival maps? How can we create spatial visualizations that are true to the scholarship of urban history? Nathan was vital in answering those questions.”

“I thought if I could give visitors to the site the perspective of a scholar and a teacher, I’d be making a contribution,” Connolly adds.

The 200-plus maps and thousands of HOLC area descriptions contained within Mapping Inequality have drawn more than one million people to the site. Visitors can select a city’s map and click to zoom in on an area or explore a description. Much of the data is downloadable.

Besides earning its share of laurels from The Chronicle of Higher Education, National Geographic, and Slate, each of which has included it on lists naming the best sites on the internet, Mapping Inequality is a magnet for activists, policymakers, and politicians. Several Democratic candidates in the last presidential election cited redlining in their housing platforms—a nod to the raft of data the project has made available, as well as its reach. The Environmental Protection Agency has cited Mapping Inequality as a key resource in its efforts to highlight environmental justice and systemic racism.

And as the site continues to grow, adding new data and functions, it has become a go-to tool for scholarly researchers, some of whom have applied its data to reconfigure their historical views of their own hometowns. Others have correlated the urban geography that redlining created with neighborhoods that suffer from excessive heat.

Mapping Inequality can also help its visitors identify the forces and individuals behind redlining. Such knowledge can be of use to housing advocates and policymakers seeking ways to overcome centuries of discrimination. Coining strategies to counter the self-serving advantages that real estate developers and politicians have built into modern development schemes, such as the massive property tax breaks and large-scale gentrification one sees in Baltimore, might give activists half a chance to fight them.

“It’s important to have well-informed Black viewpoints up front as we consider these developments,” Connolly says.

Real Estate and the Jim Crow South

The Mapping Inequality project isn’t Connolly’s first examination of race and real estate.

Fresh off earning a PhD from the University of Michigan, Connolly came to Baltimore in 2008, self-identified as an American and Caribbean historian, considering African American history a meeting place of these interests. His PhD dissertation—later to be published as A World More Concrete: Real Estate and the Remaking of Jim Crow South Florida, an extensive look at the housing travails faced by Blacks in and around Miami—won him several academic and writing awards.

“It’s been important to me to recognize that things work at multiple levels, and that a variety of factors and people have created the particular world I’m looking at,” he says. “I always work across boundaries.”

Connolly’s aim is to inform public audiences about wrongs from the past that echo loudly in the present, especially discrimination in housing and racial segregation. In laying out the deeper context behind racial inequities, Connolly has become a national voice on the intersection of American politics, capitalism, culture, digital media, and urban history.

Now the Herbert Baxter Adams Associate Professor of History, as well as the director of the Racism, Immigration, and Citizenship program at Johns Hopkins, Connolly is an acute observer of economics and racism at scales both large and small.

In A World More Concrete, Connolly confronted the Jim Crow–era class and cultural distinctions among American Blacks, Afro-Caribbeans, and property owners of all races in Miami, his hometown. His dissection of inequities there represented a fresh way to unravel the knot of development, geography, and history—what scholars call “the built environment.”

“Nathan’s work on south Florida is path-breaking,” says Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, Professor of African American Studies at Princeton and author of Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership.

What you usually see when we look at the history of housing are these binary stories—white actors on one side, Black actors on the other. [Nathan’s] work disrupts all that. It adds in different voices and actors who paint a fuller picture of the real estate landscape in the American South, which includes Black property owners who exploited Black renters.”

—Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor

Professor, Princeton

Connolly’s investigations into the history of discriminatory practices have given activists some ballast in their fight against powerful institutions.

“A World More Concrete is kind of my bible—I call it ‘the housing advocate’s digest,’” says Daniella Pierre, president of the Miami Dade NAACP. “It shows us that everything we see happening in [Miami’s] Colored Town and in other Black neighborhoods has happened before. They’ve just changed the names for those practices. Because we have that knowledge, we can shape our narratives as we battle for what’s right.”

The Personal Roots of Real Estate Research

Though born in Connecticut, Nathan Connolly’s family has origins in the Caribbean and South Florida, where he lived for most of his childhood. The women of his family, he says, continue to be keepers of the family history and, at times, defenders of Old World notions of propriety.

His family roots led Connolly, as a graduate student, to incorporate South Florida into a larger pan-Atlantic vision that included the islands and aspects of the British colonialism that had reshaped them. His upbringing in Florida also gave him an education on the racist history of the American South. Post-colonial family life taught him the intimate costs of racism as well. Race meant something in his family—in fact, many things, and ones not always as clear as Black and white.

“I’m the darkest person in my family, and by a few shades,” Connolly says. “That could sometimes mean suffering racial prejudices from extended relatives, themselves people of color.”

To be able to understand the world better, Connolly knew he’d have to cross lines—cultural, economic, and racial ones. And to gain the kind of access and mobility to make that crossing, he’d learned that even academic achievement offered no clear guarantee.

Several generations of Connollys had sought out opportunities via higher education. Nathan’s great-grandfather, William “Smiley” Connolly, came to the U.S. in 1906 from the Cayman Islands. Smiley spoke seven languages, studied at Howard and Penn, and became a dentist, musician, and preacher. Yet, his Blackness barred him from a university appointment, or even a public-school teaching position in the islands. Connolly has included Smiley’s story in his latest book about Caribbean migration to the United States, a family history. Research to date revealed that, when Smiley died in 1938, the Baltimore Afro-American ran his obituary under the headline, “Prof. W. S. Connolly.”

As a Baltimore resident and professor himself, Smiley’s great-grandson feels the weight of that irony. In his current position at Hopkins, Connolly sees a larger relevance to the history of Black intellectuals and university life. The eminent Black scholar W.E.B. Du Bois once received letters of recommendation from Johns Hopkins’ first president, Daniel Coit Gilman, and lived in Baltimore for two decades. Yet, he never was invited to study or teach at Johns Hopkins. Likewise, Kelly Miller, who in 1887 became the first Black to attend Hopkins, was never asked to join the faculty. It has only been within the past few decades that Black faculty members have been granted tenure. And even since then, their numbers remain low.

The Connolly family saga and the university now resound together in a research program that Connolly and several other scholars across campus have formed. Inheritance Baltimore is a multifaceted three-year collaboration designed to increase African American scholarship on campus, strengthen the ties between humanities courses and the racial history of Baltimore, and recognize the achievements of past Black educators and scholars in the making of academic disciplines.

The point for Connolly is to challenge even the most intimate and genteel bigotries by crossing boundaries. Inheritance Baltimore will create more bandwidth for scholarship that will be applicable to larger questions about race in the U.S.

“The main question I’m now asking in all my work,” Connolly says, “is, how does racism change the questions we ask, and how can ending racism become at least part of the answer?”